[This article is Part II of a CAM series on Brazil’s upcoming election.—Editors]

In Part I of our series, we reflected on some of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s personal and political background, as well as his success during two terms as president of Brazil. We also highlighted one of his long-time political rivals, former São Paulo governor Geraldo Alckmin. Alckmin‘s sudden and unexpected leap from the right-of-center Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB), a political party he co-founded and led for 33 years, to the left-of-center Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) in December 2021, opened the door for him to become Lula’s vice-presidential running mate in the upcoming presidential election.

Before the publication of “Part II: Is Lula Under Threat?” Brazil aired its first presidential election debate on Sunday (August 28). A total of 12 candidates took to the stage, all vying for the top political post in the country. However, the two top seeds, by far, are former president Lula, with 45% of votes according to a recent Datafolha report, and incumbent head of state Jair Bolsonaro, who trails with 32%.

Bolsonaro opened the debate floor by questioning Lula, his query prefaced by one strategic word—“Corruption,” was the first word out of his mouth. After reasserting his posture he continued: “During 14 years of PT governance, Petrobras fell into debt by R$900 billion reais” (approximately $172 billion USD at today’s exchange rate—September 8, 2022), without providing any data to validate his claim. Bolsonaro went on to characterize Lula’s administration as “the most corrupt in Brazil’s history.”

Refuting the allegations, Lula reminded his rival that “no other president of the republic launched more investigations to uncover corruption than our government.” He went on to cite measures and legislation his administration implemented to fight the scourge, including the “Transparency Portal, inspection of the CGU (Ministry of Transparency, Supervision, and Control), Information Access law, Anti-Corruption law, Anti-Organized Crime law, Anti-Money Laundering law, and authorizing the AGU (Attorney General’s Office) to combat corruption.”

Political theatrics aside, clashes between Lula and Bolsonaro, as expected, dominated the spotlight. Boosted media ratings in Brazil are driven by their showdown. The same holds true for international eyes prying on the country’s election run. In effect, attention has been diverted, by and large, from the elements that put Lula behind federal prison bars in 2018, displacing him from the last presidential election while he led all polls to defeat Bolsonaro and all other contenders.

The same dynamics from the past remain in place. Moreover, the recent political alliance between Lula and Alckmin, the former president’s political enemy for years on end, has stirred the support of the Workers’ Party (PT) base. The combining factors have led to this tumultuous moment, intrigue that begs the question, “Is Lula Under Threat?”

As if that weren’t enough, Argentina’s vice president, Cristina Kirchner was, as the saying goes in Brazil, “born again” when an assassin’s firearm jammed as he attempted to shoot her at point-blank range. Identified as Fernando André Sabag Montiel, a 35-year-old Brazilian national who had been living and working in Argentina as a driver, the incident is a reminder of growing political hatred in the region and the extent to which an individual or groups are willing to go to achieve their aims.

In Brazil, militia groups—former or current police officers and firemen, including white-collar city officials involved in criminal activities—have metastasized from Rio de Janeiro and spread across the country. Also, neo-Nazi groups are a phenomenon plaguing Brazil ever since the end of World War II. Facing defeat, Nazi generals would strip themselves of their SS uniforms, redress in civilian clothing, and sail across the Atlantic, reconstituting their lives and uniting with their network of support groups in the South American giant, as well as Argentina, Paraguay, Chile, Bolivia, the United States, and elsewhere. It should come as no surprise that Brazilian nationals have traveled to Eastern Europe to fight in Ukraine against Russia.

Lula has promised the creation of a Ministry of Indigenous Affairs if re-elected as president. Speaking at a campaign event in Belo Horizonte, he told supporters that “illegal mining will no longer exist” on Indigenous land and that “an Indigenous man or woman will serve as minister in this country. Prepare yourselves because FUNAI (National Indian Foundation) will no longer be run by a white man with green eyes. It will be run by an indigenous man or woman.” However, neither the former president nor his vice-presidential running mate, Geraldo Alckmin, has presented a de-Nazification, decolonization, or anti-militia proposal while campaigning.

Lula and Alckmin Head-to-Head

Politically infused accusations between Lula and his anything-but-expected alliance with Alckmin ran the gamut from softball to full-blown incendiary dating back to 2006. Lula was seeking re-election that year and Alckmin was his main opponent. Both candidates would reach the second round of voting, facing off, mano a mano, for the presidency.

I was living in Prado, southern Bahia, watching some of the debates with my friends in the small town and First of April Landless Workers Movement (MST) camp. They were then, as they are now, 110% pro-Lula. Throughout the re-election campaign many of them would take to the streets with their red and white Lula and PT banners, caps, and t-shirts in support of his second mandate. Contrarily, Alckmin’s name was mud. The guy did not stand a chance then and, if it were not for his cozying up to Lula, he would not stand a chance now.

Here’s a replay of some exchanges that took place between the two during their debates and public speeches:

- On June 17, 2006, Alckmin questioned if Lula was the ringleader of a criminal gang referred to as the “40 Thieves.” Speaking at an event hosted in Americana, a city in the state of São Paulo founded by disgruntled confederate politicians, soldiers, and supporters who fled to Brazil following the U.S. Civil War, Alckmin said, “Based on his character, I believe that it is difficult for president Lula to speak about this issue.”

- Four months later, on October 24, during a televised presidential election debate, Alckmin accused Lula of being involved with political corruption associated with the PT. He described Lula’s government as being “halted in the economy and accelerated in scandals.”

- The following day Lula responded that he “couldn’t believe he was facing a candidate. I thought I was facing a deputy at the door of a prison cell.” He stressed that his adversary failed to show the same level of decorum as other politicians he had debated in the past, citing Fernando Collor as an example. A former Brazilian president (1990-1992), Collor stepped down from office just prior to being impeached on charges of embezzlement. Lula proceeded to say that the television audience had witnessed “a bit of Brazil’s political elite,” adding that, “possibly the governor [Alckmin] still has yearnings for the days of torture” in police probes. Lula reiterated that all criminal activities were being investigated.

Public disputes between Alckmin and Lula only intensified as the years went by. The ugliness of their rows continued in the lead-up to and during the 2018 presidential campaign where Alckmin would make a second run at the highest political seat in the land. In doing so, he would throw his weight behind Lula’s illegal imprisonment precisely when he led all polls to win a third term in office.

- The year 2016 marked on-going, insatiable anti-Lula and anti-PT media campaigns. Accusations revolved around Lula being gifted a three-story apartment in exchange for favoring corporate interests in government contracts. During this period, Alckmin said “Lula is the Workers’ Party. Lula is the portrait of the PT, a political party steeped in corruption, without any commitment to issues related to ethics. He has no limits.” Speaking at an event where he presented new cars to the military and civil police, Alckmin went on to say “what we’re witnessing is very sad. Society wants this case to be investigated vigorously and that justice prevail…Brazil is taking an important step forward. It is painful but necessary.”

- Later that day, Lula released a public statement that said, in part: “It would be more beneficial to the people of São Paulo if the media would ask and governor [Alckmin] explain the embezzlement of funds for public metro works, as well as school lunches, the violence against students and the made-up numbers of homicides in the state. Instead, he tries to deflect attention toward an apartment that is not and has never been Lula’s property.”

- PT’s former president, Rui Falcão, also chimed in, tweeting: “Instead of attacking Lula, Alckmin should tend to his own government, which takes the food out of kid’s mouths.”

- In December 2017, Alckmin ramped up the attacks: “After leaving Brazil flat broke, Lula now says he wants to return to power, otherwise, he wants to return to the scene of the crime. Does the Workers’ Party deserve yet another chance? Be assured that we will defeat them at the polls.”

- In August 2018, Lula published an article stating that Alckmin and Brazil’s interim president, Michel Temer, “are two faces of the same coin: the neoliberal agenda that has sunk the country…and has currently put the country in one of the worst crises in its history under the baton of the illegitimate government of Michel Temer. This is easily demonstrable from the position of their respective political parties when they voted in the National Congress in favor of heinous measures such as the constitutional amendment on public spending caps and workers’ rights reform.”

- Alckmin went on to release anti-Lula television ad campaigns even after the former president had been imprisoned and barred from participating as a candidate by Brazil’s Electoral Justice department. One ad stated: “It’s also in your hands to prevent the return of corruption and robbery to take hold of the country…It is you who can prevent the release of a prisoner [Lula] convicted of corruption”

- In another TV ad, a photo of Lula is cropped behind an image of prison cell bars. The announcer says: “That’s why Lula’s been imprisoned. But it’s not only for this reason that Brazilians fear PT. Nobody wants the same crew responsible for the largest corruption scandal the world has ever seen to return to office again.”

- Alckmin would go on to produce more audacious TV campaign ads, one of which depicted both Lula and Bolsonaro as being politically aligned to former Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez.

When word first got out that Alckmin was being contemplated as Lula’s vice-presidential running mate, PT leaders released a signed petition titled: Manifesto Against the Lula Alckmin Affiliation. It recalled that Alckmin “publicly supported the coup and neoliberal operation” that resulted in the impeachment of former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. The letter also emphasized that his governorship of São Paulo was marked by attacks “against workers in general, against public servants, against health and education, against public security, against Black people, against youths and students, against residents of periphery communities, against the environment.” The letter, however, came to no avail.

Just four years down the road, despite Alckmin’s PSDB serving as the main opposition party to the PT during their 13.5 years in office, not only has he been brought on as Lula’s vice-presidential running mate but he has also been tasked with helping to develop the government program presented to voters in the October 2022 presidential election.

Lula’s accomplishments as president, his precipitous incarceration, tedious release, restoration of his political rights, and triumphant return to the political scene are amply covered in the press. Little if any review or analysis has accompanied the major and minor players pumping out these stories. What interests might they possess in who becomes president? How can that person, any person, be hamstrung by the machinations of the powers that be?

Big Media in the Southern Tropics

In May 2022, Time magazine published a photo of Lula, decked out in suit and tie, on the cover of its print edition. The headline read: “Lula’s Second Act: Brazil’s most popular leader seeks a return to the presidency.” The appearance was that of a foreign leader, of an equally foreign country, to which the international publication held no historic ties.

Sixty years ago, Weston C. Pullen, Jr., served as vice president of broadcasting for Time magazine, then known as Time-Life. On July 24, 1962, he would sign an agreement with the Brazilian media corporation, Globo, under the direction of its heir, Roberto Marinho, thus providing the news outlet with 300 million cruzeiros (approximately $6 million USD at the time). In comparison, TV Tupi, the second largest media broadcaster of the time, was established with $300 thousand USD.

Thanks to the capital investment, Globo was transformed, literally overnight, into the largest media outfit in Brazil. The terms of the contract were outlined by two specific areas of cooperation. Effectively, Time-Life would (1) provide technical assistance to Globo and (2) a joint venture would be established by the two partners.

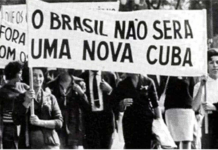

After spending just two years feeding the public day-in and day-out anti-communist propaganda and other forms of entertainment, Globo conspired in the 1964 overthrow of former Brazilian President João Goulart. Moving forward, they would spare little praise for the imposed military leaders following the coup.

Goulart would die in 1976 under very mysterious circumstances while in exile in Argentina. Although no autopsy was performed on his body, it was reported that the cause of death was a heart attack. His passing came at a time when Operation Condor was in full swing across mainland Latin America.

Three years later, in 1965, one year into Brazil’s official military dictatorship, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Carlos Lacerda, declared the Time-Life and Globo partnership to be illegal. He denounced the foreign investment to be in contravention of Brazil’s constitutional article 150, which prohibited foreign capital to dictate or influence any form of management or acquire property holdings at a communication company.

The following year Marinho testified at a parliamentary inquiry (CPI) stating that, “two American organizations—NBC and Time-Life—had approached us to work together on the enterprise’s development.” Although the two media groups had reached out to Marinho “almost simultaneously” he opted for Time-Life for having made its launch into television “a few years back with great success.” He went on to state that the joint venture contract never went into effect but that the technical assistance portion had. To fulfil this commitment, Time-Life sent Joe Wallach, a directorial adviser to provide support to the accounting department, as well as to train Globo’s technical operations team.

Though Wallach denied having played any role in managing Globo’s financial affairs, much less influencing the TV station’s programming, the inquiry found the Time-Life and Globo partnership to be illegal. It concluded that the U.S. media giant was, in fact, exerting influence over the intellectual orientation and administration of Globo. The ruling, however, like most CPIs, held no legal ramifications or punishment for either Globo or Time-Life. Symbiotic dancing, however, between big media and its shaping of socio-political landscapes seemed a natural bidding for Time-Life and its parent corporation, Time, Inc.

Three decades prior to the Globo and Time-Life agreement, Charles Douglas (C.D.) Jackson was senior executive at Time, Inc. After his tenure at the media giant, he served as deputy chief of the Psychological Warfare Division of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA; liaised between the CIA and Pentagon under U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower; and served as his adviser on psychological warfare in 1953 and 1954. In 1960, after his extensive career in U.S. intelligence and covert operations agencies, C.D. Jackson would return to the private sector, becoming publisher of none other than Life magazine.

In her book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters, Frances Stonor Saunders describes Jackson as being “an ardent cold warrior.” The extent to which he carried on his work was often documented in his personal log files.” In one entry produced seven years after the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, Jackson wrote: “Matters were progressing on LIFE on an article by Gordon Dean to remove the guilt complex from America on the use of the A-Bomb.”

Globo’s reach, virtually throughout Brazil and beyond, its influence and success blossomed to heights unimaginable during the 20-year (1964-1984) military dictatorship. During this period Marinho would build his fortune to become a Brazilian billionaire. The stretch lasted through the military presidency of Army Marshal Artur da Costa e Silva (1967-1969) who once stated, “Let the rich become more and more rich so that, thanks to them, the poor become less poor.” Globo continued its lucrative journey through the presidency of Emilio Médici who, in 1972, spoke on TV, “Every night I feel happy whenever I watch the news. Why? Because on TV Globo news the world is in chaos but Brazil is at peace… It’s like taking a sedative after a day at work.”

Meanwhile, two of Globo’s biggest competitors at the time, Excelsior and Tupi, the former being one of the sole media outlets that produced reports against military rule, continued their slow declines. Both would have their broadcasting license revoked by the totalitarian state.

Assassinations, disappearances, torture and censorship marked the two-decades-long dictatorship. Unable to get their political position or demands broadcast on TV, a group of militants kidnapped U.S. Ambassador Charles Burke Elbrick in September 1969. By holding him captive, the media were forced to report on the resistance to the military dictatorship and specific demands of the MR-8 and National Liberation Action to secure Elbrick’s release, which included a swap for 15 political prisoners.

There seems to be no definitive answer, despite the country’s Truth Commission, as to how many people lost their lives as a result of the military dictatorship in Brazil. Truth and Reconciliation commisions in Chile and Argentina registered over 40,000 and 30,000 deaths, respectively, during military rule in those countries.

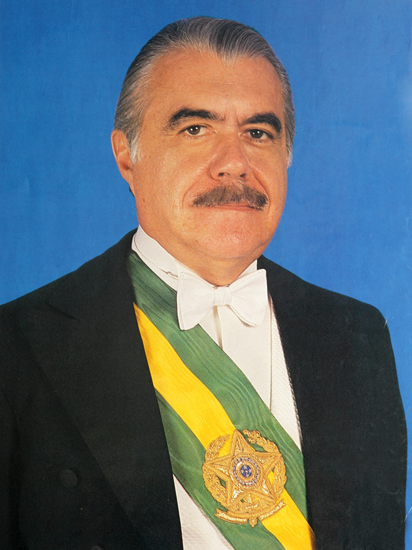

Brazil’s re-democratization process culminated with the presidential election (via an electoral college) of Tancredo Neves in January 1985. Military rule was declared finished, although Brazil’s military police, one of the most lethal security forces in the country and founded during the dictatorship, exists to this day.

Hours after his victory, Tancredo attended a private lunch with Marinho, as well as the former governor of Bahia, strongman Antonio Carlos Magalhães and a host of other top government officials to discuss the transition from military to civilian rule and the formation of his government. Three months later, never having assumed office, Tancredo Neves was dead, victim of what was reported to be a complicated surgery to remove an infectious tumor in his intestine. In his place came José Sarney, a long-time supporter of autocratic rule.

While Lula’s debonaire profile picture graced the cover of Time this year, in a classic, balancing the scales of objectivity act, Bolsonaro made Time’s 100 List in 2019 and 2020. For his first appearance Time wrote that, albeit a “complex character,” the president “represents a sharp break with a decade of high-level corruption.” It also published that, although Bolsonaro is a “poster boy for toxic masculinity, an ultraconservative homophobe intent on waging a culture war,” he is “Brazil’s best chance in a generation to enact economic reforms that can tame rising debt.”

Lula has experienced, first-hand, the blunt reality of hostile media coverage. According to a 2016 report prepared by the Media Studies and Public Sphere Laboratory (Lemep) Jornal Nacional, Globo’s hallmark news show, produced 13 hours of negative coverage of Lula compared to 4 hours of neutral coverage, and not a single second of positive reporting. The report was prepared between December 2015 and August 2016. Portions of the findings were presented by one of Lula’s defense attorneys, Valeska Zanin Martins, during a press conference where “abuses against him [Lula] in Brazil” were delivered to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland. [NOTE: The word “brunt” (line 1 of the paragraph) is a noun so I don’t know what word he meant as an adjective (perhaps “blunt” or “brutish”?]

All things considered, Lula has promised to implement communication and media regulations if re-elected as president. His vow has drawn the naked ire of some of his most fervent opponents in the industry.

Multinational Lawfare in High Gear

In April 2018, Lula was imprisoned on charges of corruption and money laundering. The case against him was part of the politicized evolution of the Car Wash investigations: judicial inquiries into corruption at state and private enterprises such as Petrobras and Odebrecht, as well as businessmen and politicians.

The investigations were made possible due to additional legal tools and mechanisms provided to Brazil’s federal police, investigators, and prosecutors during Lula’s government. White-collar crimes had long run amok in the South American giant and Brazil’s first president from the PT, having shined shoes as a young boy on the streets of São Paulo, wanted to send the right message. As time went by, reckless abandon by Brazilian authorities, the type Lula may have knelt before so many years ago with his shoe polish kit, including foreign interference would ensnare the Car Wash probes.

Shortly after being sworn in as president in January 2019, Jair Bolsonaro named Sergio Moro, the federal judge who condemned Lula to 12 years and 11 months in prison, as his Minister of Justice. Many viewed the appointment as payback for helping to pave the way for Bolsonaro’s meteoric rise to power. After assuming office Moro, together with the former director of the federal police, Mauricio Valeixo, signed cooperation agreements with the FBI, one of which included a biometric data-sharing accord against criminal and terrorist suspects. The agreement did not specify the terms of who is considered a terrorist, simply stating that there only needs to be “reasonable suspicion that they are a terrorist.” It goes on to define criminals as anyone who has received a judicial sentencing of more than one year in prison.

Moro and FBI Go to Work

Placed onto the federal court in 1996, Moro, just two years later, would attend a one-month training course for lawyers at Harvard Law School. Then, in 2007, he was accepted to participate in a U.S. State Department-sponsored program. The curriculum taught attendees methods of detecting and combating money laundering.

In a 2009 cable published by WikiLeaks, Moro’s name is listed as a participant in a conference titled “Illicit Financial Crimes.” The venture, part of the umbrella “Bridges Project,” was supported by the U.S. State Department and hosted in Rio de Janeiro October 4-9. Its aim was to further consolidate bilateral training between U.S. and Brazilian officials in order to apply the law. Not only did Moro attend the forum but the federal judge was asked to address the audience concerning 15 common issues involving money-laundering cases in Brazilian courts.

An apparent favorite of Moro’s, so much so that she was part of the selection process that chose him to participate in the “Illicit Financial Crimes” seminar, was Karine Moreno-Taxman, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Resident Legal Counsel. Assigned to the U.S. embassy in Brasilia in 2007, her work involved establishing contact with Brazilian authorities and organizing specialized training courses where she would speak about the need to form joint task forces to fight corruption and money laundering. Present at her workshops were Brazilian federal police, prosecutors and judges, including Moro. In one speech, referencing the need to pursue officials under investigation, Moreno-Taxman stated, “Society must feel that such a person really abused their job and demand their conviction.”

Before assuming her new role at the U.S. embassy, Moreno-Taxman’s career involved training state officials, NGOs, and private sector institutions in the United States and other countries about conducting international investigations related to money laundering and other transnational crimes.

Connections and contacts between Moro and U.S. officials are more extensive than the few examples given here and merit further review.

For the FBI’s part, 13 agents from the bureau, including the head of international corruption department, Leslie Backschies, liaised and cooperated with investigators and prosecutors involved with the Car Wash trials. Four agents even traveled to the 13th Federal Court in Curitiba, the tribunal in which Moro presided and convicted Lula, to interrogate Alberto Youssef, a businessman testifying under a plea bargain involving corruption probes into Brazil’s majority state-run oil company, Petrobras. Agents from the bureau, as well as representatives of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), also provided additional evidence to Brazilian investigators prosecuting the same case.

As far back as 2004, former director of the FBI in Brazil, Carlos Costa, stated that the bureau was conducting operations in the country. Testifying before the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), he confirmed that the FBI financed and directed Brazilian Federal Police operations, resulting in their “subordination to U.S. authorities.”

In 2018, Petrobras, which trades shares on the New York Stock Exchange, agreed to pay US$ 853.2 million to conclude investigations by the DOJ, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Brazilian prosecutors into corruption charges. The payout brought an end to the DOJ’s monitoring of the company related to Car Wash corruption probes. While 20% of the fine was expected to go to U.S. authorities and shareholders, 80% was intended for reinvestments in social and educational programs in Brazil and monitored by the MPF.

According to the Inter-Union Department of Statistics and Socioeconomic Studies (Dieese), Brazil suffered losses of more than 4.4 million jobs and 170 billion reais (approximately $32.5 billion dollars at today’s exchange rate) in direct foreign investments due to the Car Wash investigations.

George “Ren” McEachern headed the FBI’s International Corruption Squad and oversaw most of the investigations associated with the Car Wash on behalf of the DOJ. In a 2018 interview titled “Car Wash Operation Is an Example for the World,” McEachern stated, “the courts in Curitiba sent out the message that Brazil is becoming clean.”

Invited as a guest speaker at the Fourth Annual International Compliance Congress and Regulator Summit, hosted in São Paulo in May 2016 and attended by 90 members of São Paulo’s Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, McEachern told the audience that the FBI was offering technical support to investigators in relation to “encryption, mobile telephones, and cloud data.” The special agent also noted that the bureau had established a cybernetic analyst headquartered in Brasília.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

Though opportunities were available, Lula refused political asylum. Before surrendering to federal police agents on April 7, 2018, after being held up for two days at the ABC Metal Workers’ Union headquarters in São Paulo—the site of many political debates, organizing, and mobilizations during Lula’s days as a workers’ union leader in the 1960s and 1970s—the ex-president spoke to crowds of supporters.

“I am not afraid of them. I would even like to have a debate with Moro about the charges he’s brought against me. I’d like for him to show me some proof. What crime have I committed in this country?…because I dreamed that it was possible to govern this country involving millions of poor people in the economy, adding university seats, and employment for the poor?”

Determined to prove his innocence by squaring off with his accusers in court, Lula defiantly remarked that he would not “kill” himself or “flee” Brazil. “I am staying right here. This is where I was born, this is where I belong. The only thing I fear is betraying the people of this country.”

After serving one and a half years of his almost 13-year sentence, Lula was released from prison in November 2019. All 25 inquiries and charges against him were eventually dropped and his full political rights restored.

The barrage of cases against the former president were viewed by many jurists and legal experts as a clear-cut case of lawfare—strategies employed to attack, undermine, weaken, and unseat political opponents through manipulative legal and judicial maneuvers. Minus the blood, think of lawfare as Operation Condor manifested through the rule of law, judicial system, social media bots, and the hypnotic babble of multiple news outlets.

To some degree, this method proves more effective for its apparent subtleness, its appeal to the cidadão de bem (model citizen) to respect local authorities (and their foreign cohorts and colleagues) as they uphold the legal system, compared to the rash killings, assassinations, disappearances, and torture of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s to achieve similar goals.

Lawfare has succeeded in undermining and even overthrowing some mainland Latin American governments (i.e., Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Paraguay). Most recently, Argentina’s vice president, Cristina Kirchner, in almost a repeat of what happened to her when she was the head of state, has been accused of corruption in yet another graft probe, two of her homes raided by Argentine police in August. Responding to the accusations, she referred to her opponents as the “judicial party,” adding that the move “is an instrument of persecution and banishment of popular leaders.”

In a slight reversal of events in Brazil, Deltan Dallagnol, former head of the Car Wash Task Force in Curitiba, Delcídio do Amaral, a former senator from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul and ex-employee of British multinational oil company, Shell, and other officials involved with Lula’s prosecution and imprisonment are now accused by his legal defense team of abuse of power, false testimony, and causing moral damages. It is unclear, also unlikely, if any of these individuals will spend a day in jail even if condemned in the courts.

Stay tuned to CovertAction Magazine for the forthcoming and final Part III of “Is Lula Under Threat?”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com