Danger lurks with election of large number of pro-Bolsonaro governors and radicalization of Bolsonaro’s supporters who refuse to accept election results.

The impeachment of Peruvian President Pedro Castillo was “carried out within the constitutional framework.” This comment was offered not by Lisa Kenna, the current U.S. Ambassador to Peru and former CIA agent, but by Brazilian president-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Similarly, Chilean President Gabriel Boric immediately recognized Castillo’s vice president, Dina Boluarte, as Peru’s new head of state.

On the morning of December 7, then-President Castillo proceeded to dissolve Congress after the legislative body, lagging well behind at a 7% approval rating (September 2022), attempted to impeach him for a third time in just one and a half years in office. Article 134 of Peru’s Constitution permits the dissolution of Congress based on obstructionism and, having experienced the first impeachment attempt in his fourth month in office, it is precisely what Castillo faced throughout his brief tenure as head of state.

“They intend to blow up democracy and disregard our people’s right to choose,” Castillo said. During a publicly televised address just before his impeachment, he said that the dissolution of Congress would be a “temporary” measure where he would govern “by decree” until new congressional elections were held.

“The United States categorically rejects any extra-constitutional act by President Castillo to prevent the Congress from fulfilling its mandate,” tweeted Kenna. One day before this post she had met with Peru’s defense minister, Gustavo Bobbio Rosas, a retired brigadier general who had been sworn in fewer than 24 hours earlier.

Apart from her ambassadorship in Peru and nine years at the CIA, Kenna also served as a senior aide to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the ex-CIA director who once made it clear that he “was the CIA director. We lied. We cheated. We stole. We had entire training courses.”

Immediately after Castillo attempted to sack Congress, the legislative body cited constitutional Article 113, successfully voting to impeach the embattled president based on “moral incapacity.” Later that same evening, Castillo, an Indigenous campesino and public school teacher who, similar to Lula, was also a union leader who led strikes and speaks not in the tongue of political elites but local vernacular, was charged with rebellion and conspiracy and imprisoned. Days later, a judge ordered that the impeached president remain in pre-trial detention for 18 months.

With the presidency vacant, Vice President Dina Boluarte was sworn in as Peru’s new head of state. Faced with mass protests, she declared a nationwide “state of emergency,” deploying the military onto the streets. In January, Boluarte said she “had never embraced the ideology” of Perú Libre and was expelled from the party in which Castillo campaigned for president.

“The United States welcomes President Boluarte and hopes to work with her administration to achieve a more democratic, prosperous, and secure region,” stated Brian A. Nichols, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs. He added, “We support her call for a government of national unity and we applaud Peruvians while they unite in their support of democracy.”

Just one day before Castillo’s removal, Argentinas vice president and former two-term president, Cristina Kirchner, was convicted on charges of corruption and sentenced to six years in prison and disqualified from holding public office. Analysts and supporters attribute her case to on-going lawfare campaigns waged against progressive governments in the region—the pink tide. Kirchner’s court case and verdict were only possible after an assassin’s firearm jammed as he attempted to shoot the vice president at point-blank range. Identified as Fernando André Sabag Montiel, a 35-year-old Brazilian national who had been living and working in Argentina as a driver, the incident is a reminder of growing political hatred in the region and the extent to which individuals or groups are willing to go to achieve their aims.

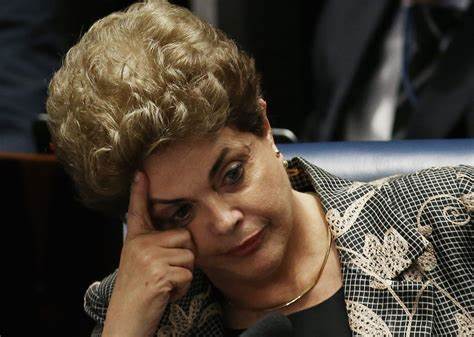

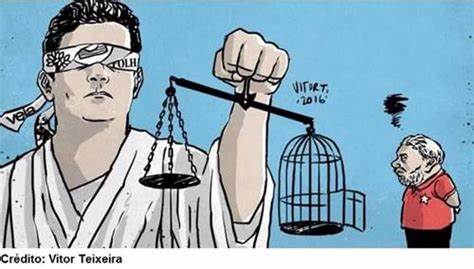

Though their socio-political contexts may differ, Castillo’s ouster did not occur in isolation from similar events witnessed in Brazil, starting with the removal of former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. The good news, at least for now, is that Lula has been released from prison, allowed by the same judicial system that initially put him behind bars four years ago to run in this year’s presidential election and, ultimately, defeated incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro.

However, this is a one-sided story. It paints only a portion of a larger landscape. Speaking about the return of the so-called pink tide, Tatiana Berringer de Assumpção, a professor of international relations at the Universidade Federal do ABC, said, “they are, in certain terms, more fragile, however…more numerous. They’re more fragile precisely due to their economic fragilities but also because of their own political limitations. Still, the synergy manifested between them can do away with their inertia, therefore, enhancing their potential.” However, with no effective response to lawfare, will progressive governments in mainland Latin America fulfill their potential?

Another less-discussed section of Brazil’s political canvas involves a closer breakdown of the 2022 general elections where a new parliament and governors were voted into office. Like Lula, Castillo also won the presidency. Just over a year into his mandate he was impeached, as was Dilma, and imprisoned, as was Lula in 2018. Unimpeded for the most part, lawfare continues to perfect its efficacy and voraciousness.

What Happened? First-Round Election Results

Five of Brazil’s seven Amazon region states—Roraima, Rondȏnia, Pará, Amazonas, and Acre—have either elected a pro-Bolsonaro governor in the first-round general election or a second-round gubernatorial candidate who favors the former president. Illegal mining and the expansion of agribusiness, industries detrimental to Indigenous communities and the environment, are among their proposals or implemented policies.

Taking home 56.2% of votes, Romeu Zema, another Bolsonaro loyalist, was re-elected as governor of the state of Minas Gerais. Part of Brazil’s southeast region, including the states of Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, Minas Gerais was the sole state in this electoral zone, home to the largest percentage of eligible voters (43%), where Lula defeated Bolsonaro 48.3% to 43.6%.

Remaining true to form was Rio de Janeiro, Bolsonaro’s stronghold home state, where the incumbent president defeated Lula 51.1% (4.8 million votes) to 40.7% (3.8 million votes). Fellow Liberal Party (PL) member Cláudio Castro was re-elected to serve as Rio’s state governor in the first round of voting. Bolsonaro also defeated Lula 47.7% to 40.9% in the state of São Paulo. His gubernatorial candidate and former Minister of Infrastructure, Tarcísio de Freitas, went on to compete in an election runoff against the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate, Lula and Dilma’s former Minister of Education Fernando Haddad. According to an October 19 poll, Freitas led the race 55% to 45% and, indeed, he defeated Haddad in the decisive second-round vote.

Another key note in São Paulo’s gubernatorial race was the first-round knockout of Rodrigo Garcia of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). Serving as the main political opposition to the PT during Lula and Dilma’s presidencies, it is the first time the PSDB has been booted from the governor’s mansion since 1994.

While some party members viewed the loss as the party’s demise, it bears no consequence for the former party leader, co-founder and ex-governor of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin. In December 2021, the seasoned politician leapfrogged from the PSDB, his party for more than 30 years, to join the left-of-center Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB). His new political membership occurred just ten days prior to the deadline for presidential hopefuls to be officially registered with a political party.

To the consternation of Lula’s supporters, the move paved the way for Alckmin to run as his vice-president candidate. When word first circulated that he was even being contemplated for the position, PT leaders released a signed petition titled: Manifesto Against the Lula Alckmin Affiliation. It recalled that Alckmin “publicly supported the coup and neoliberal operation” that resulted in the impeachment of former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. The letter also emphasized that his governorship of São Paulo was marked by attacks “against workers in general, against public servants, against health and education, against public security, against Black people, against youths and students, against residents of periphery communities, against the environment.”

The PT faced lesser disappointment in gubernatorial races in Brazil’s northeast region where their candidates, Fátima Bezerra (Rio Grande do Norte), Elmano de Freitas, (Ceará) and Rafael Fonteles (Piauí) were victorious. The PT also won a total of 68 legislative seats, two of which, Valmir Assunção (Bahia) and Dionilso Marcon, both members of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), were elected to Congress.

Most notable in the first-round general election was the number of ex-ministers, seven in total, who served in Bolsonaro’s cabinet elected to the Senate or Congress. Newly elected senators include former Minister of Women, Family, and Human Rights Damares Alves (Federal District); former Minister of Science and Technology Marcos Pontes (São Paulo); former Minister of Agriculture Tereza Cristina (Mato Grosso do Sul); former Minister of Regional Development Rogério Marinho (Rio Grande do Norte); and former Minister of Justice Sérgio Moro (Paraná)—the same former federal judge who convicted and sentenced Lula to 12 years and 11 months in prison on trumped-up charges of corruption and money-laundering. Incoming congressmen include former Minister of the Environment Ricardo Salles (São Paulo), as well as disgraced former Minister of Health Eduardo Pazuello (Rio de Janeiro).

Even before Lula defeated Bolsonaro in the second-round presidential election, Veja magazine was prepping the scene for another run at lawfare. In an article titled “Bolsonarista Advance in Congress Will Be a Tough Challenge for Lula,” Robson Bonin wrote, “Lula has made it to the second round of the election believing that he would be elected without having to assume accountability for past PT corruption.”

Citing the wave of pro-Bolsonaro representatives winning seats in the legislature, comprising the largest group in the body come 2023 with a total of 99 congressmen and 14 senators, the article went on to affirm that “Bolsonaro, consequently, will have influence over the Legislative branch even if he loses to Lula in the second-round presidential election.” That sentiment was echoed by Estadão newspaper. In a piece titled “Lula May Win But Bolsonarism Has Already Seen Victory,” Marcelo Godoy noted that the election of so many ex-ministers in Bolsonaro’s cabinet clearly demonstrates the “vitality of the right.”

During a press conference following the first Lula-Bolsonaro runoff debate, the incumbent president squeezed his former Minister of Justice, Sergio Moro, in front of the cameras to “please give a statement about corruption.” Positioning himself accordingly, the ex-federal judge reaffirmed that Lula “lies.” Moro proceeded to associate Lula to organized rebel gangs who, over a three-day period in May 2006, spearheaded attacks throughout São Paulo leaving 59 police officers and penitentiary guards dead. In response, death squads and the police killed 505 civilians over the next two weeks. “I’m against Lula and PT governance that want to, as Alckmin has previously said, ‘return to the scene of the crime.’ This is unacceptable.”

Moves to appease the financial sector and possibly avoid virulent, well-funded Bolsonarist opposition to an eventual Lula government were under way prior to the first-round presidential election. On September 27, less than a week before voting, Lula attended a private dinner in São Paulo hosted by João Camargo, founder of Esfera Brazil, and attorney Marco Aurelio de Carvalho, of Grupo Prerrogativas. Diners included businessmen and important figures in the financial sector who publicly expressed their support for and donated funds to Bolsonaro’s re-election campaign or allied politicians.

In the lead up to the first-round election, Ometto had donated a total of R$8.8 million (approximately $1.6 million at today’s exchange rate) to political parties and candidates aligned with Bolsonaro. Also in attendance was Henrique Viana, founder and CEO of Brasil Paralelo, a website that produces films and other content that recounts the history of Brazil from a right-wing perspective. With more than 375,000 subscribers, the company has seen a meteoric rise parallel to Bolsonaro’s ascendance.

Foreign Interference?

Despite the Ministry of Justice and Public Safety registering 939 electoral crimes and 307 detentions during this year’s first-round general election, the president of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), Alexandre de Moraes, said, “the election occurred in peace,” and without any “serious difficulties.”

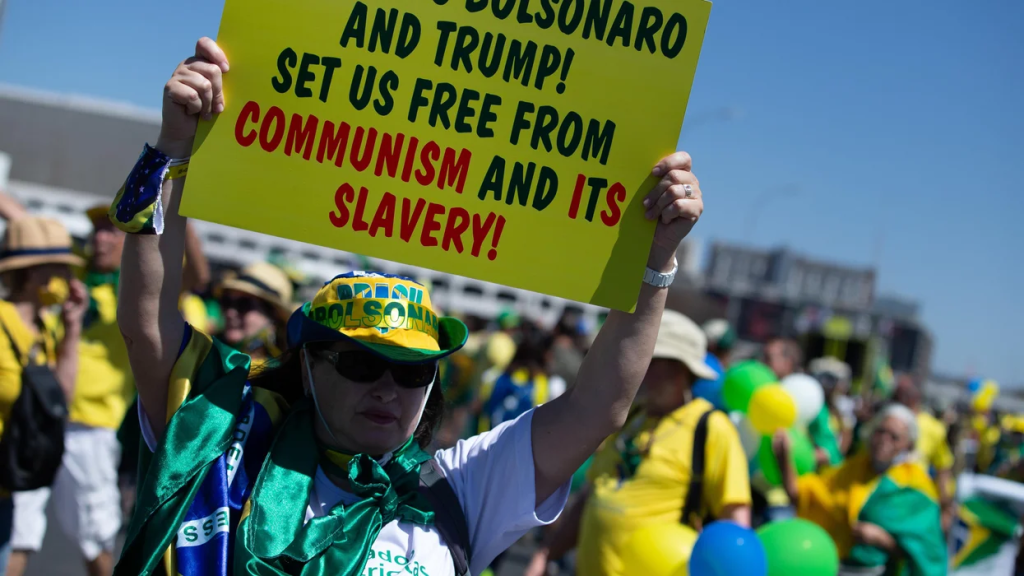

Foreign support for Bolsonaro was expressed not only via hyperbole but also capital inversion connected to his re-election campaign. Former Trump adviser and founder of Breitbart News, Steven Bannon, stated that Brazil’s presidential election is the “second-most-important election in the world,” adding confidently, “Bolsonaro will win unless it’s stolen by, guess what, the machines.” The media mogul has maintained close relations with Bolsonaro’s son and congressman, Eduardo Bolsonaro, since 2018, designating him as representative of his conservative international movement in Brazil.

Jason Miller, owner and director of the U.S.-based social media website Gettr, and former adviser to President Trump, sponsored political events in support of Bolsonaro’s re-election campaign before the start of the official electoral period, which began on August 16. Brazil’s electoral laws banned political campaigning prior to this date.

However, Gettr supported at least four events promoted by the think tank Liberal Conservative Institute (ICL) between September 2021 and June 2022. ICL is headed by Eduardo Bolsonaro, along with attorney and ex-adviser to the Ministry of Education, Sérgio Sant’Ana. Hosted events included two CPAC conferences, referred to as the “largest conservative event in the country,” as well as two conservative regional congresses called “Profound Brazil.”

Gettr was established in July 2021 with the support of a foundation associated with Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui, an associate of Bannon.

On March 12, Congressman Filipe Barros spoke at a “Brasil Profundo” event in Londrina, Paraná. He told attendees that Lula was the “first president of the republic to be imprisoned or the first person in the country’s history who was acquitted by the Supreme Federal Court, a clear and distinct interference in the electoral process. They did this so that he could compete in the elections against Bolsonaro in the hope that Lula wins but I’m sure that won’t happen.”

During a Conservative Congress held June 11-12 in Campinas (São Paulo), speakers explicitly requested votes for the incumbent president. “You all are the elite troops…Each one of us must obtain at least one thousand votes for our president Bolsonaro,” said Jorge Seif, ex-Secretary of Culture and Fishing and, at the time, a congressional candidate for the state of Santa Catarina. In attendance at the event, Dan Schneider, executive director of CPAC, stated, “When I return to Brazil next year, I want to be here to celebrate a victory, not to regret a defeat.” He concluded: “Come on Brazil, let’s win.”

For his part, Miller stated, without directly mentioning the upcoming presidential election that the situation is “critical not just for Brazil or the United States, but for all of Western civilization…If we do not defend and embrace our freedoms now, they will be lost forever. This is the time to exercise our God-given rights to free speech, free expression, free press, free assembly, and free worship.”

Concerning Brazil’s electoral legislation, Isabela Damasceno, President of the Electoral Rights Commission-Order of Attorneys-Minas Gerais branch, pointed out that foreign companies are prohibited from sponsoring events of an electoral nature. This includes Gettr’s live broadcasting of pro-Bolsonaro motorbike rallies in Ribeirão Preto, as well as Americana, a city founded by disgruntled U.S. Confederate soldiers, politicians and supporters who fled to Brazil in the wake of the U.S. Civil War. Damasceno stressed that this type of relationship “breaches regulations,” adding that “there’s been an attempt to conceal the sponsorship so as to avoid scrutiny by the electoral justice department concerning these types of donations…The irregularities in relation to the episode as told to me are alarming.”

Marcelo Weick, an attorney and member of the Brazilian Academy of Political and Electoral Rights (Abradep), also stressed that, with respect to political campaign funding, “money received from a foreigner,” regardless if it is a private individual or legal entity, “is prohibited since the 1940s.” Such means of backing “not only interferes in the transparency of the electoral process and equal opportunity but also, and more unsettling, our national sovereignty…This is a very serious problem that must also be investigated.”

Lawfare Review

To date, lawfare—falsely accusing political leaders of crimes in order to remove them from office—has been practised and seen more success in the U.S.’s proverbial “backyard” than any other political region on Earth. These actions are always in concert with the Global North, and are incapable of execution by officials and their interests solely without the Global North.

Example: Lawfare, as it has been employed in Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Ecuador, Brazil and Argentina, has yet to see the light of day in efforts to undermine, weaken or overthrow the Cuban government. However, lawfare is a crucial aspect of the U.S.-imposed blockade, an extraterritorial measure aimed at punishing third-party countries for engaging in commerce with the Caribbean island.

Apart from geography, what sets mainland Latin America apart not only from Cuba but other regions where it has not succeeded? For acknowledging lawfare’s existence and explaining its function from one place to the next, with critical and even leadership support from the “front yard,” is no longer the question. What is Brazil doing to clean house and political risk assessment to prevent these machinations from incubating and revisiting Lula in his third and final presidential term?

Vow to Regulate Media

Having been the victim of multiple hours of negative media coverage and not a second of positive reporting, Lula vowed to implement standard media regulations during the campaign trail. “I never imagined that lies spread via cellphones could have so much force on the internet,” he told a group of Evangelical representatives. He also reminded attendees that, for many years, he was bogged down trying to convince churchgoers that PT members were not demons simply because of the party’s red-colored logo or because he sported a beard.

Such media coverage served as a primer for lawfare in Brazil and Lula’s imprisonment precisely when he led all polls to win the 2018 presidential election. “Well, he can issue an executive order” in regard to implementing media regulations, one lady told me. True, however, pundits and talking heads have already made their case. The mere hint of this move would be met by calling Lula a “dictator” and “tyrant,” one who trashes the spirit of “free speech.” Theoretically, issuing an executive order to implement better media regulations could restart the lawfare ball rolling.

However, short of implementing basic media regulations and the democratic expansion and support to Brazil’s alternative media landscape, it is hard to tell how any independent, progressive media group will be able to keep up and compete with the magnitude of Globo and other well-funded mainstream media outlets.

Strengthening the Base

With Lula imprisoned (2018-2019), Fernando Haddad served as the PT’s presidential candidate substitute, going toe to toe with Bolsonaro in the 2018 election. Less than a week before the election, Mano Brown, lead artist of the rap group Racionais MC’s, took to the stage of a political rally in Rio de Janeiro. Reneging on his promise to “never again attend” such an event he had decided, in this instance, to come and “represent me”—that is, “me” in the plural, collective sense of his childhood periphery community in São Paulo and all periphery communities in major Brazilian cities. In no mood for the “festive gathering,” Brown challenged the audience to come to terms with the fact that “blindness that affects the other side also affects us.”

Seated right behind him were Haddad and his wife, Ana Estela Haddad, and vice-presidential running mate Manuela D’Avila of the Communist Party of Brazil; former left-wing presidential candidate Guilherme Boulos of the Socialism and Liberty Party; Lula’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Dilma’s former Defense Minister Celso Amorim; musicians Chico Buarque and Caetano Veloso; liberation theology priest Leonardo Boff; and a host of other important political and cultural figures. Marielle Franco’s mother, Marinete da Silva, was also in attendance, the only one sustaining a smile throughout Mano’s talk.

Denied credit for having awakened and cultivated the socially conscious, thus, politicizing a generation of youths starting in the 1990s, artists such as Racionais MC’s, authors and poets from the periphery literature movement (also referred to, mainly by the market, as marginal literature), and other grassroots organizations helped propel Lula to his first presidential win in 2003. Lacking these ingredients, previous presidential runs (1989, 1994, 1998) had all come up short despite the gradual escalatory push provided by the PT and allied political parties, workers’ unions, liberation theology, and untold liberal organizations, groups, progressive media, etc.

Back on stage in Rio, Brown said, “If at any point the communication of these people [pointing to the guests behind him] fails, then they’ll pay the price. Communication is the heart and soul of everything and if they’re not speaking the language of the people, they’re going to lose for sure, understood? Speaking well of the PT in front of PT fans is a piece of cake. There’s a whole bunch of people who aren’t present who need to be won over, if not, we’ll fall into the abyss…You people are screwing up and now you’re going to pay the price.” Boos poured in from the crowd. Brown held his composure, briefly scanning the audience, “If you all let me speak everything will be cool but I’d just as well stop altogether. Fuck it…Blindness is what kills us, not fanaticism…Return to the base”

When asked if he agreed with Mano’s remarks, Lula said that he “was right,” adding that “I like that guy like fuck. He’s gutsy.”

Part and parcel of the “communication” divide conjures another statement a friend from Prado, in southern Bahia and one-time grassroots MST member once told me—that the PT “não abre o leque” (doesn’t broaden its range). The limitation implied also speaks to a disconnect between political leadership and technocrats from base level, community supporters. That Lula was denied a resounding first-round presidential victory exemplifies deeper political polarization than some are willing to admit. Strengthening and improving communication with the base, broadening their range, might very well be the first step to regaining grassroots support, the shock troops required to advance public policies, defend against the spread of misinformation and disinformation associated with lawfare, and propel progressive platforms into a future when Lula is no longer president. The creation of the new Ministry of Indigenous People, which will be overseen by Sônia Guajajara, is one example of how Lula’s administration is “broadening its range” during his third presidential term.

In 2020, Campinas State University, one of Brazil’s most prestigious educational institutions, included Racionais MC’s seminal album “Surviving in Hell,” on its list of reading for students preparing to take the school’s entrance exam. Albeit the first time a music CD was endorsed as study material, the designation drew ire from conservatives for it, like others of the genre, dispelled Brazil’s creation myth and PR mainstay of being a country based on racial democracy.

Before Lula Is Sworn In

Jair Bolsonaro, the personality and figurehead the world has come to know over the past four-plus years, should have been defeated handily in the first-round presidential election. His track record as a politician, 27 years serving as a Rio de Janeiro congressman and counting just two proposals approved, is as low a bar as they come. That he was not defeated in 2018 and survived to a second-round decisive vote against Lula, the most popular president in Brazil’s history, leaving office with a record 83% approval rate, is a telltale sign of entrenched, polarizing factors canvasing Brazil’s socio-political portrait, an image more profound than Bolsonaro himself. Galvanized, mobilized, and fearless, his supporters brought the country’s 2022 presidential election to a nail-biting conclusion, a victory for Lula no less, but by less than two percent.

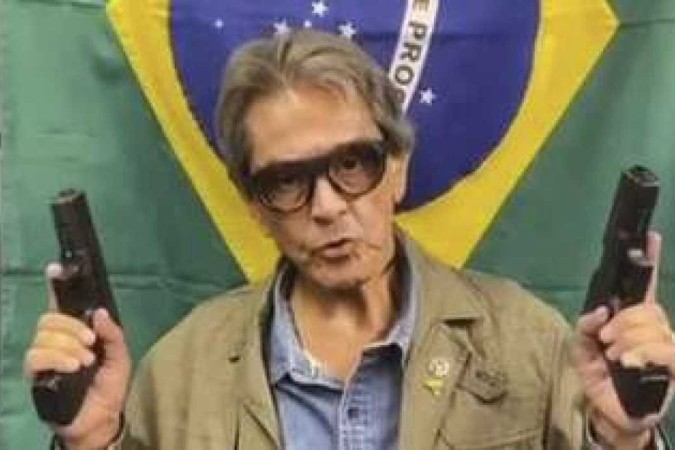

On Sunday morning, October 23, one week before voters went to the second-round polls, former congressman and Bolsonaro ally Roberto Jefferson grabbed his rifle and fired more than 20 rounds and tossed two grenades at federal police officers outside of his home in Rio de Janeiro. Based on non-compliance with the terms of his house arrest for helping to create a social media militia, his detention was ordered by Supreme Federal Court judge and TSE President Alexandre de Moraes. In an official statement Moraes repudiated Jefferson’s “cowardly” remarks and “abject aggression” directed against Supreme Court Justice Cármen Lúcia. The ex-congressman had posted on social media that the federal judge was a “prostitute and “whore.”

After a standoff, Jefferson surrendered to officers and was eventually taken into custody. Two officers were injured by shrapnel during the attack. Before the day’s end, Moraes had suspended the former congressman’s house arrest and reinstated his imprisonment. He has since been charged with four counts of attempted homicide. Although Bolsonaro tweeted that he rejects the “statement made by Mr. Roberto Jefferson against Judge Carmen Lúcia and the armed action against Federal Police agents.”

Prior to victory, Lula forewarned his supporters, “We’re going to have a problem, that is, we’re going to win the election. We’ll defeat Bolsonaro but Bolsonarism has been birthed. Following [the elections] we must raise awareness among society so that our people will not consolidate Bolsonarism as a definitive form of politics in Brazil.” The president-elect has also stated that he will not seek a fourth term as head of state.

Moving Forward

Without question, Lula’s run has been long and wide. It dates back to the mid-1960s when he was employed at a metal factory. It was during this period that his pinky finger was severed in a work-related accident. Then, in the mid-1960s, Lula, almost reluctantly, joined the metalworkers’ union. Years later he would confess that his preference at the time was either hitting the pitch for a football match or watching Brazilian soap operas. Rising through the workers’ union ranks over the years, he would be elected as president of the ABC Paulista Metalworkers Union in 1975. It was during this period, amidst military dictatorship violence and repression, that Lula led mass strikes for increased workers’ rights.

Lula’s trajectory, in fact, dates back even further, back to his childhood in the early 1950s. Migrating from drought, poverty and widespread hunger, the death of four siblings before reaching the age of five in the interior of Brazil’s northeast state of Pernambuco to the hustle and bustle of São Paulo, Lula would shine shoes and sell peanuts and oranges to help feed himself and his family. It dates back to his earliest, most formative years, learning to exhibit good “character…respect…dignity” and that he “must be bold” from his “illiterate” mother, Eurídice Ferreira de Melo—Miss Lindu. “She died as she was born, illiterate,” Lula said.

However, nothing of the sort would diminish lessons he learned from her, a battered woman who eventually rounded up her children and left Lula’s father. “I’d look at my mother’s visage and never saw her lose faith. She’d say, ‘Today we don’t have [food], but tomorrow we will.’ This is the belief that I was raised on…and we made it through. We survived.”

Acknowledging that this is his farewell presidential mandate, that the baton is ready for transfer, is a heads up to the younger generation. That baton, whether they are prepared to receive it or not, will be theirs in the coming four years. It will be a propitious and arduous four years, during which the conditions for lawfare will be ripe. Acute boldness is a must to help carry this administration through.

Postscript

Unlike his first-term presidential victory in 2003 and re-election four years later, Lula’s triumphant return to the political arena, represented by a phoenix-like third term, is met with through-the-roof expectations. The extended bucket list is due, on one hand, to Bolsonaro’s bombastic and corrosive leadership as president and, on the other, Brazil’s inherent socio-political structure, its society and its history and culture of open-ended dispossession.

Despite pressing internal and regional matters of importance banging at the door, one of Brazil’s leading progressive media outlets, just days after Lula’s victory, posed the question: Can Lula Help Negotiate (Peace) with the War in Ukraine? The government transition process had hardly begun and here was a media outlet imposing the president-elect upon a multi-faceted conflict playing out a continent away.

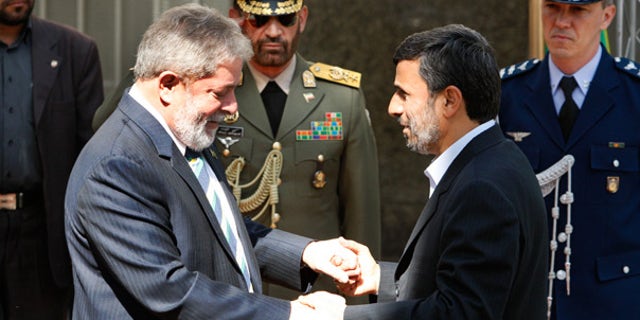

Such a proposition, however, did not come without merit, one that stems from the fact that, in 2010, Lula negotiated a nuclear deal between Iran and the United States. His efforts, shunned by former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and former President Barack Obama, led him to question, “How do these people want to make a deal without dialogue?…I remember that Hillary Clinton worked hard against my idea to go to Iran. She even called the Emir of Qatar and asked him to convince me not to go. When I arrived in Moscow and met with [Dmitry] Medvedev, I found out Obama had called and asked him to help persuade me not to go.”

Projecting Lula back onto the international stage is a prerogative pushed by his team of advisers and handlers. Hosting a South American conference to protect and preserve the Amazon rainforest, as well as reintegrating Venezuela into regional political frameworks are just two priorities on the list.

To date his team remains quiet about whether or not the president-elect will attempt peace negotiations closer to home. The armed conflict between the Mapuche and Chilean government, which has included the militarization of the entire southern region (from the Biobío River to the tip of Chile’s southernmost coast), has seamlessly traversed from Sebastián Piñera’s government to Gabriel Boric’s. If there is one issue that unites far too many mainland South American governments, it is the response meted upon Indigenous people whenever they mobilize to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Similar matters reverberate within Brazil. Over a ten-day period, between the 3rd and 13th of September, four Indigenous adults and two Indigenous youths were killed in areas where land conflicts with loggers, miners or agro-industrialists prevail. Those killed included members of the Pataxó, Guaraní-Kaiowá, and Guajajara nations. During the same period, Cleiton Isnard Daniel, a 15-year-old Indigenous youth, committed suicide.

In the state of Bahia in 2021, 616 people were killed by the military police. Of that total—at least where the race of the victim was identified—603 were of African descent (98%). Compiled by the Security Observatory Network, the data were published in a study titled Skin Target: The Color the Police Extinguishes. It shows that Black people in Bahia, a state governed by progressive politicians over the past 16 years, comprise almost the totality of victims killed by the police. “Public security institutions…are not linked to left-wing discourses,” said Bruno País Manso, a researcher at the network and co-author of the study. A consensus among security officials is that, by “eliminating…the threat, order is established.”

South America’s giant lives and dies by its societal mainstay—“racial democracy”—promoting itself as being an at-ease, laissez-faire, miscegenated melting pot. What might have been Mano Brown’s response to being cursed out by a disgruntled Bolsonaro supporter at the 2022 World Cup in Qatar as opposed to Gilberto Gil is anybody’s guess. When faced with hard, factual numbers, the myth of “racialized democracy” is so outweighed by levels of institutional violence, racism and discrimination that it might have made Belgium’s King Leopold blush.

While Bahia’s percentage of Black people killed by the police is comparable to the state of Rio de Janeiro, the latter held the largest total number in 2021. Among 1,600 victims, 1,214 were Black people. The Skin Target: The Color the Police Extinguishes study also points out that last year, by compiling seven Brazilian states—Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo— 3,290 people were killed by the police. Of that total, 2,154 were Black people.

Back in 2019, Rio de Janeiro’s police force killed at least 1,546 people. I reiterate “at least” for the body count, according to the Instituto de Segurança Pública, was compiled only from January to October that year. One of the victims, nine-year-old Ágatha Félix, was shot in the back by policemen who invaded the Complexo do Alemão favelas on September 20, 2019. Then-Governor Wilson Witzel publicly blamed her death on people who “smoke marijuana.” Daniel Lozoya, a member of Rio de Janeiro’s Public Defender’s Office, commented, “the more the state kills, the more it strikes…young Black youths in favelas.”

Brazil’s 2022 presidential election outcome proved tight, significantly tighter than polls suggested and what Lula supporters believed was possible. Bolsonaro, as evidenced by the truckers’ highway blockage, calls for another internal military intervention, and stacking parliament with his most trusted people, also proves that he has more shock troops to absorb the loss and move forward. Beyond pushing buttons inside a ballot box to promote, advance and defend Lula’s political project and policies, it is difficult to gauge where the same level and amount of enthusiasm and fervor will come from when the going gets tough. If the current moment is not bad enough, tougher times will emerge.

As president-elect, Lula has already made more than 80 promises to help salve the country’s economic woes. Policies aimed at remedying increased hunger (Brazil has been placed once again on the UN’s Hunger Map) are squarely on the table. Last year, the country’s pubic health service registered, on average, eight hospitalizations per day of babies at least one year of age due to malnutrition. If Lula fulfills just half of those vows, his third-term presidency might very well be considered a success.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com