Evidence collected by The Intercept revealed that Operation Car Wash, an anti-corruption investigation led by Brazilian Federal Prosecutors and the Federal Police from 2014 to 2021, received support from the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

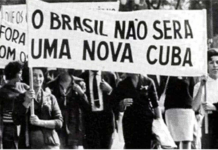

The operation had a significant impact on Brazilian politics, including the undermining of the government, which led to the impeachment of then-President Dilma Rousseff (PT), the imprisonment of then ex-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), as well as the rise of right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro, and Sergio Moro, the case’s judge who became Bolsonaro’s Minister of Justice.

While Sergio Moro’s involvement in the Car Wash investigation initially elevated his status and positioned him as a symbol of anti-corruption efforts, the operation’s controversial proceedings and allegations of bias began to undermine his credibility.

The leaked “Vaza Jato” messages and other controversies raised doubts about the fairness and impartiality of the investigation and the judicial process. As a result, Lula’s conviction was eventually overturned, allowing him to become president again. Furthermore, Sergio Moro’s decisions as a judge in Operation Car Wash faced scrutiny, leading to the annulment of some of his rulings and casting doubt on the integrity of the investigation as a whole.

The fate of the operations is still at stake, with news referencing the case still being released on a weekly basis. Last month, on May 9, 2023, Gilmar Mendes and Dias Toffoli, Judges of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF), voted to consider former Judge Sergio Moro biased in yet another case related to Operation Car Wash.

In 2021, a group of 20 U.S. congressmen sent a letter to the United States Department of Justice requesting that the Biden administration make public information about how American investigative agencies cooperated with Operation Car Wash in Brazil.

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s lawyers also demanded that authorities clarify whether there was informality or irregularity in this cooperation.

What is the importance of Operation Car Wash to the United States? Why did the FBI participate in anti-corruption investigations in Brazil? How common is it for American law enforcement agencies to invest in overseas operations? Why did American congressmen criticize that initiative? Are there implications for bilateral relations between the United States and Brazil?

Operation Car Wash

Operation Car Wash was revealed to the press in 2014 as the largest anti-corruption action in the history of Brazil. The investigations targeted criminal organizations involved in money laundering, including agents in the public and private sectors. Its inauguration pointed out irregularities in the domestic and international operations of Petrobras, the largest state company in the country.

The conducting of the operation involved articulation with a group of governmental bodies, including the Federal Police, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office, and the justice system of various states in Brazil, notably the nucleus in the state of Paraná, led by Federal Prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol and Judge Sergio Moro.

The operation charged hundreds of individuals, issuing bench warrants and more than a thousand search-and-seizure warrants, and there were also leaked private messages and telephone calls. It froze millions of reais and triggered an economic crisis and the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff as well as prison terms for various high-profile Brazilian businessmen and politicians.

Among the companies involved in this case were Odebrecht and Petrobras, which are transnational companies, and it also attracted the involvement of elites and judicial systems of other countries. The operation was officially closed in 2021, and the investigations still under way were taken over by the Special Acting Group in the Fight Against Organized Crime, which is responsible for organizing task forces which assist with the work of the Federal Police.

“Vaza Jato” leaks

The so-called “Vaza Jato” refers to a series of investigative reports released in 2019 by the news website The Intercept Brasil and other media outlets. These reports brought to light a series of revelations about Operation Car Wash as one of the largest corruption investigations in the history of Brazil.

According to the reports, the leaked material was obtained through an anonymous source and consisted of messages exchanged between prosecutors of the Car Wash task force, especially the then-federal Judge Sergio Moro, and prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, as well as other team members.

The messages revealed private conversations that suggested questionable conduct on the part of the prosecutors and the judge, including alleged ethical violations, improper coordination, bias, and undue interference in the direction of the cases. The reports also pointed to collaboration between the task force and Judge Moro, raising questions about the impartiality of the judicial decisions made within the Car Wash operation. The impacts of these revelations contributed to questioning and revisions regarding the practices adopted during Car Wash and the way the investigations were conducted.

What the FBI has to do with it?

Within the vast volume of information contained in the leaks, we became aware of the assistance that the FBI provided to the legal experts and law enforcement officers involved in the investigation and trial of the case.

As part of the investigations, Brazilian and American authorities cooperated specially in the sharing of information and joint investigations. This was partly due to the fact that the corruption scheme involved international companies and financial operations that went through banks in the United States. Additionally, the systemic corruption in Brazil also posed a concern for the United States government regarding the political and economic stability of the region.

That was not the whole story, though. The leaks made public very close and informally (if not illegally) close ties between FBI agents and members of Operation Car Wash. In the beginning of the operation in 2015, a delegation of 17 American agents including prosecutors from the Department of Justice and FBI agents, traveled to Curitiba for a secret meeting with members of the Federal Prosecutor’s office and with lawyers of business people under investigation in Operation Car Wash.

Through this meeting, they sought to establish a partnership with the FBI in the investigations, which included negotiating with the lawyers of those collaborating in the investigation and sending them to testify in the United States, avoiding restrictions from Brazilian laws.

The agendas of the meetings were not released at the request of the American agents, and the Ministry of Justice only found out about this visit when the meetings were already under way. By law, however, mediation with foreign police forces should be performed by the Department of Assets and International Justice Cooperation (DAIJC) of the Ministry of Justice.

When asked for clarification, Prosecutor Daltan Dallagnol responded that the Ministry of Justice should consult the U.S. Department of Justice, “because they asked us to keep it confidential.” They also asked Prosecutor Vladimir Aras, the Head of the International Cooperation Sector of the Federal Prosecutor’s Office, to avoid publicizing the names of the American investigators to the Brazilian government to avoid “making noise” with their international partners.

These statements reveal a favoring of U.S. partners over their Brazilian affiliates, thereby infringing on the legal terms of the Accord concerning Judicial Assistance in Penal Matters (1997), which establishes the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice in intermediating relationships with the U.S. Department of Justice.

For this reason, Lula’s defense team requested that the Brazilian Supreme Court demand clarification from the Ministry of Justice regarding any potential cooperation between Operation Car Wash and the FBI. In 2021, a group of 20 American congressmen sent a letter to the Department of Justice of the United States requesting that the government make public information about how U.S. investigative agencies cooperated with Operation Car Wash in Brazil.

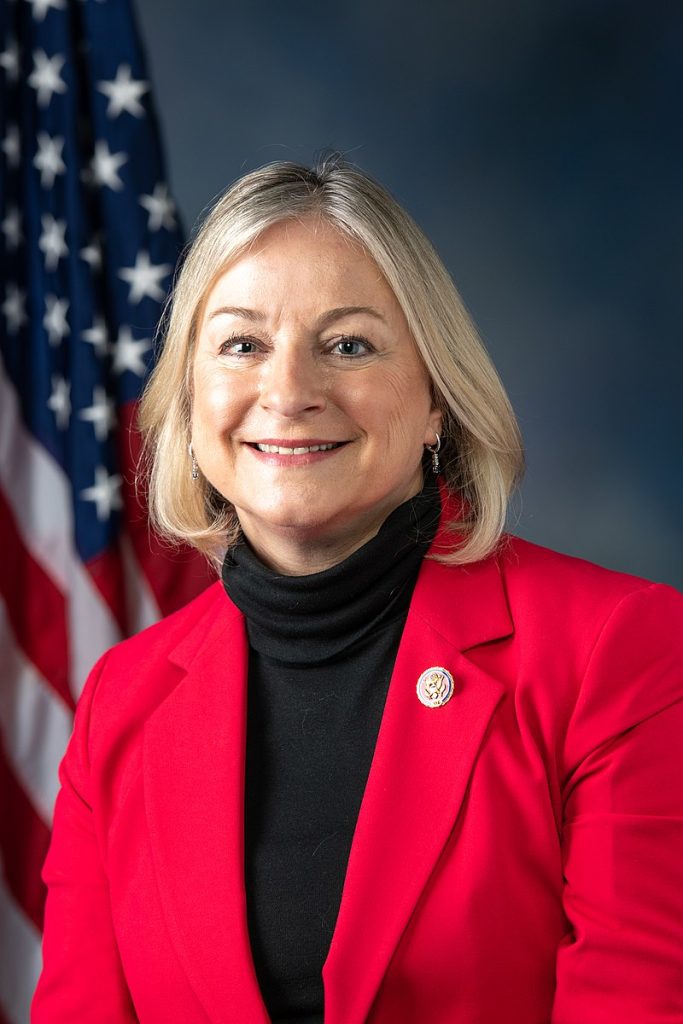

“If the DoJ played any role in the erosion of Brazilian democracy, we must take action and ensure accountability to prevent it from ever happening again,” stated Democratic Congresswoman Susan Wild from Pennsylvania, one of the signatories of the letter to the DoJ, in an interview with BBC News Brazil.

Among all the concerns raised by the Congress Members is the history of U.S. interference in Latin American democracies. Susan Wild also refers to the role that the U.S. government and law enforcement agencies, such as the FBI itself, played in military coups and police brutality during right-wing dictatorships in Latin America, in the context of the Cold War. During the presidency of Democrat Barack Obama (2009-2017), the country initiated what became known as the “diplomacy of openness” making public classified diplomatic documents about human rights violations committed by the dictatorial regimes in Brazil, Argentina and Chile.

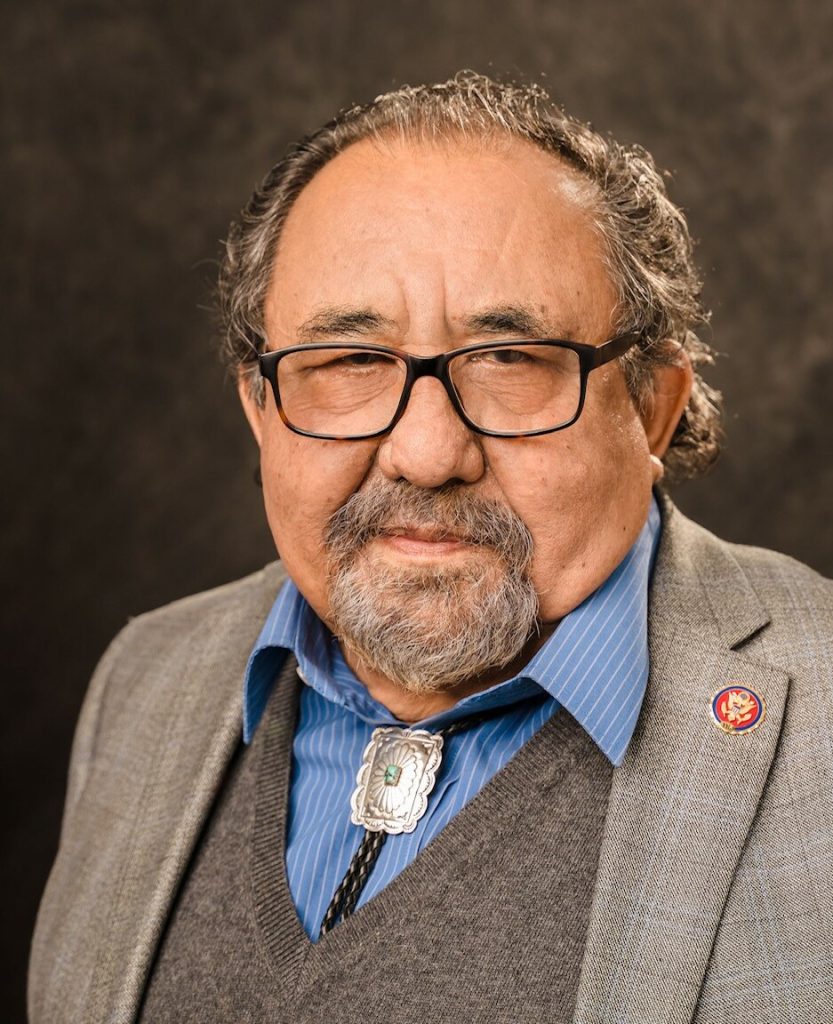

Congressman Raúl Grijalva from Arizona reinforced the point that “the United States has a dark history of intervention in Latin American internal politics, and we need to fully understand the extent of U.S. involvement (with Operation Car Wash) to prevent any unacceptable implication from happening in the future.”

One of the FBI agents who participated in Operation Car Wash, Steve Moore, also emphasized to the press the FBI works with groups of Brazilian police officers who have been “carefully selected and trained by the United States for many years,” what indicates to us that it is not a new or exceptional case.

Policing and Politics: from the war on communism to the war on crime

If the report reveals that Operation Car Wash was one of the most important investigations that fostered partnerships between the Federal Police and the FBI, it is worth noting that it was not the first one.

Training and assistance programs for foreign police forces have been a permanent part of U.S. international policy vis-à-vis Latin America since the early decades of the 20th century. As an alternative means of intervention, the practice has been regarded as instrumental for the dissemination of social control mechanisms in the light of the U.S.’s national interests and security agendas. Throughout history, various challenges and narratives have oriented these programs.

Since the 1930s, one of the key missions of the crusade against communism was the development of programs to modernize Latin American police forces, Brazil’s included, with a view to developing their capacity to contain the expansion of the insurgent groups that were destabilizing governments in the region. The goal was to disseminate an anti-communist hard-line stance in Brazilian police institutions, build an intelligence network oriented toward internal security, and guarantee the longevity of allied governments that could safeguard U.S. hegemony over its zone of influence.

In the 1970s, such programs gained a new impetus, replacing or overlapping their predecessors, when Richard Nixon and his successors declared the so-called “War on Drugs,” whose battlefields extended internationally.

Latin America occupied a prominent place in this context, as it is home to key countries involved in the production and transit of many of the illegal drugs that are consumed in the U.S. Brazil was a recipient of police assistance throughout this period, initially seen as a focus for insurgent groups and, later, as a route for international cocaine trafficking. Since then, other “threats,” such as terrorism, money laundering and corruption have also been added to the list.

Since then, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established and has also maintained close ties with Federal Police agents through its offices in Brasília, São Paulo and, more recently, Rio de Janeiro.

For a long time, the drug enforcement agenda guided the cooperation between American and Brazilian police forces. Through this partnership, the FBI and DEA were able to transfer resources and technology to train Brazilian police, finance and propose joint operations, as well as influence the formulation of laws and public policies aimed at combating drugs.

Progressively, though, other issues have taken center stage in the concerns of U.S. law enforcement in Brazil, such as terrorism, money laundering and corruption, as evidenced by the Car Wash case.

Policing the world

The ability of U.S. agencies, such as the FBI, to disseminate their knowledge and guidelines was related to the development of prestige in relation to the Federal Police and a transnational network of policing at a global level. The dialogues show that Brazilian police officers felt honored by the proximity of the FBI agents.

A striking point is the informality that characterizes these relationships. During the Car Wash operation, joint investigations, exchange of evidence, and extradition requests did not go through the Ministry of Justice, partly due to the mistrust that both institutions had of the Dilma Rousseff government.

It can be observed that the relationship established between the agencies of both countries goes beyond the terms provided by international agreements. As part of this informality, access to information about the activities of U.S. law enforcement agencies in Brazil is very restricted, as the report attests. This kind of external interference bypasses government control mechanisms and, therefore, strains the sovereignty of the State itself, while at the same time being stimulated and promoted by the state agencies themselves, such as the Federal Police.

“Vaza Jato” investigations mention an event organized in 2018 by a law firm in São Paulo, CKR Law, where Brazilian and U.S. police agents were present to discuss corruption investigations in Brazil. The goal was to build communication channels that could exist parallel to governmental relations.

Thus, there is a flow of transnational relationships between U.S. and Brazilian agents, both public and private, that establish networks of trust from which they share knowledge, technology and resources. These collaborations are not exempt from hierarchies and power dynamics. The political, economic, technological resources and prestige that can be mobilized by the FBI make it a leading force in this process. It is the U.S. agencies that offer resources and knowledge to Brazilian institutions, not the other way around.

That also highlights the modus operandi of U.S. law enforcement agencies in foreign countries. Conferences, events and training sessions aid not only in the transfer of knowledge but also in the establishment of intimate and trusted networks of relationships between justice agents from both countries. There is a deliberate effort to build trust with Brazilian authorities, creating a direct channel between the police forces through which they can influence police work, investigations, law formulation and public policies.

That episode raises a series of fundamental questions for society by revealing that policing extends beyond territorial and national boundaries. The definition of agendas, objectives and strategies in the field of security and justice, the design of laws, police conduct and technologies, and the conduct of investigations are aspects defined transnationally without transparent debate in society or even within the government.

In this case, the operation had a significant impact on Brazilian politics, weakening democratic mechanisms, strengthening the rise of the far right, and causing immeasurable damage to the national economy.

What is the future of these investigations? What are the implications for the relationship between President Lula and the United States? The debate is still open, and we will continue to see its results in the coming years.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Prof. Priscila Villela is an International Relations Professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP) and vice-leader of the Transnational Security Studies Center (NETS).

Prescilla can be reached at: pvillela@pucsp.br.