While socioeconomic conditions worsen and desperation mounts, caravans heading northbound to the Mexico-U.S. border keep flowing.

Holguín, CUBA — “I’m sure you guys heard this all the time and it’s probably…cheesy and cliché but the American dream dies hard,” said The New York Times Andes bureau chief, Julie Turkewitz. “Even after…all of the problems that one knows exist in the United States—the power of the American dream, it’s powering that journey through the jungle.”

Accompanying Turkewitz’s closing remarks, part of an otherwise somber CBS Sunday Morning special news report titled “Migrants’ dangerous journey north,” was a photo of mud-soiled, ragged clothes draped over the bodies of equally worn and exhausted migrants crossing the Tapón del Darién (Darién Gap).

This mountainous jungle range separates Colombia and Panama (South and Central America), a perilous yet necessary passage for so many heading further north, toward the spoils of an imperialist war and Treaty of the Guadalupe Hidalgo.

They seek the border dividing modern-day Mexico and the United States. Despite the deprivations and hazards of the trek—accounts of murder, rape, extortion, lost body parts and contraction of tropical diseases—it is unclear if CBS’s photographer asked migrants to perk up and stand in unison for a profile image.

One fleeting moment and the snap of a camera capture them with unmistakable expressions of hope for a better, brighter economic future, if not for themselves then certainly their children. The border, America—the United States of America—is not in sight at this leg of their journey but reachable, somewhere in the horizon if not still in their dreams.

Crossing by the Hundreds of Thousands

Panama’s National Migration Service reported that 248,284 people crossed the Darién Gap by foot last year. The total, which included 40,438 children (16%), represented a 936% hike of those who had risked life and limb, packed their belongings, some their kids, to traverse the jungle stretch in 2019.

As Turkewitz noted, the Darién Gap is the “only stretch of the Americas where engineers could not build the Pan-American Highway,” the longest road in the world, connecting Alaska to Argentina.

While well-informed about the gargantuan highway and dangers associated with migrating by land through the Darién Gap en route to the U.S., absent from the CBS Sunday Morning report, which included Tyler Mattiace, a Human Rights Watch researcher based in Mexico, was a single utterance concerning U.S. foreign policies toward its proverbial “backyard.”

Some of those measures, overt economic and trade sanctions, including more subtle but highly effective media smear and lawfare campaigns, all of this preceded by Operation Condor and dirty wars, have destabilized societies across Central and South America. The result has been the provocation, intentional or not, of mass migration northbound toward the U.S. over the past years and decades.

Listening to CBS Sunday Morning, however, it was as if armed conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s against Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala, including the role Honduran and Costa Rican territories played in some of these wars, never happened. Induced by the corporate media, the historical memory of the general public blurs, as thin as Panama itself and as treacherous as the Darién Gap.

Former U.S. Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, as well as ex-National Security Council staff member turned television host and pundit, Oliver North, were spared mention regarding their roles in ratcheting up conflict in Central America, dirty wars funded, in part, via arms sold to both Iran and Iraq during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War.

For CBS Sunday Morning, which emphasised only Cuban and Venezuelan migrants in its coverage, reiterating how “Covid devastated economies across Latin America and the Caribbean” and adding a sprinkle of how “authoritarian governments and climate change are driving millions of people to leave,” not one word was said about the adverse effects U.S. and, in some cases, EU-imposed sanctions have on these countries.

Impact on Real People

As socioeconomic conditions worsen and desperation mounts, caravans heading north keep flowing. Meanwhile, the focus of attention becomes either how to deal with the plight of these migrants, without addressing the root causes of migration, or what policies can be implemented or walls erected to keep “aliens” out.

A message displayed at the end of the CBS Sunday Morning report narrowed the focus further: “It will cost New York City’s taxpayers more than $4 billion to provide migrants with housing, meals, and other services through 2024,” according to the New York City Comptroller. Subtracted from the $150 billion (USD) in lost revenue to Cuba as a result of the six-decade long U.S.-imposed economic blockade, one gets the false impression that the U.S. government and New York State are contemplating reducing their prospective reparations check to the Caribbean island to $146 billion (USD).

Maira Delgado Laurens, a Ph.D. student in Global Studies at the University of California, Irvine, describes the humanitarian situation in the Darién Gap as “an asymmetrical war impacting impoverished peoples of color worldwide. This space is traversed by peoples from various parts of the world,” one being a Yemeni I met named Zacarias. After months of trials and tribulations, a few spent in a Panamanian detention camp and crossing the jungle, he had finally made it to that fabled border northbound. Shortly after making his crossing, however, Zacarias was detained by U.S. immigration officials and promptly whisked back to his country, engulfed in a war supported by the country that deported him.

Laurens continued, highlighting that people from “the Caribbean and countries from the African, Asian, the Middle East, and American regions” attempt crossing the Darién Gap. “These individuals have endured economic hardship, violence, displacement, dispossession and state abandonment; not to mention the historical and contemporary role that wealthy Western countries have played in creating these circumstances.”

Reversal of Route

An aphorism came to mind while watching CBS’s take on the migratory crisis—Don’t force yourself where you don’t belong. Easier said than done, especially when taking into account desperate souls seeking a better life for themselves and most certainly their children. Fingers crossed, migrants will try to find greener pastures. Fingers crossed. Some university graduates and professionals in their fields end up flipping burgers or driving taxis.

Others, children it has been reported, are forced to pick crops in the fields. Some, barely teenagers, if that, end up operating industrial trucks and other heavy machinery. Countless others are physically and sexually abused. Last month, eight migrants, mostly from Venezuela, were plowed over by a truck driven by 34-year-old George Alvarez in Brownsville, Texas.

One thing is certain, from Amadou Diallo to, more recently, 15-year-old Ángel Eduardo Maradiaga Espinoza or eight-year old Anadith Danay Reyes Álvarez, both dying while in U.S. immigration custody, there is no lack of situations and scenarios in which migrants or immigrants, documented or not, find themselves once reaching, in the words of Ron Ridenour, the “devil’s own country.”

But there was another story, one that I knew of and, unsurprisingly, had received no press attention. It’s the story of Adrian “Kuba,” a young Cuban who had lived in Ecuador for seven years. At 14 years of age, he had emigrated from the Caribbean island with his parents in search of opportunities abroad. However, seven years later, at twenty-one, Adrian packed his own bags, not to embark on a journey through the Darién Gap en route to that mythic border northbound—not to say the thought had not entered his mind—but to return to his homeland of Cuba to complete his studies and start a new life.

However, seven years later, at twenty-one, Adrian packed his own bags, not to embark on a journey through the Darién Gap en route to that mythic border northbound—not to say the thought hadn’t entered his mind as “the American dream dies hard:—but to return to his homeland of Cuba to complete his studies and start afresh.

Interview

Julian Cola (JC): How was your childhood in Cuba?

Adrian “Kuba” (AK): Well, it was a fairly calm childhood in certain ways. We could play in the streets without any problems or concerns for being fined. We played all types of games with our neighborhood friends.

JC: Growing up, what were you thinking about doing as an adult?

AK: I entered this world investigating and looking for some way I could earn money in Cuba. I realized that in Cuba every business that is about food gives money.

JC: What brought you to Ecuador?

AK: Well, my parents and I went to Ecuador thanks to the free visa entry at that time [2013-2014]. We left Cuba to improve our quality of life and seek a little more financial freedom. It was very sad leaving other family members here in Cuba.

JC: What did you do in Ecuador and how long did you stay?

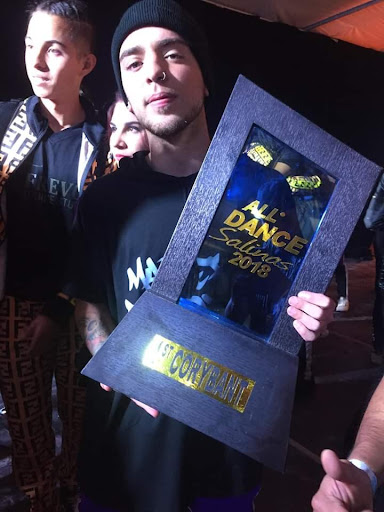

AK: I stayed in Ecuador for seven years. I completed all of my primary school studies; then I began university, pursuing a degree in Tourism. I didn’t like the degree or the education system because it seemed very mediocre and some aspects were unnecessary. I left the university, however, I have been a professional dancer since I was very young. I have skills and an inclination for dancing. I was in several dance academies, achieving many national awards from all over Ecuador, performing in the 2019 national championship together with the Frevo Studio Dance Academy. This was the institution that gave me an opportunity to dance whenever I wanted after I had arrived in the country. I became a dance teacher in an academy north of Quito where I taught Hip Hop dance. The truth is that, in Ecuador, I achieved a lot as a dancer, more than I could have ever imagined in Cuba. For that I am very grateful for Ecuador’s welcome and all the opportunities it offered me.

JC: When did you decide to return to Cuba and how did you come to that decision?

AK: I decided to return to Cuba because the situation in Ecuador was changing, along with the Ecuadorian government. Lenin Moreno came to power and the situation changed a bit. It was difficult to find work. My mother is an engineer and is unemployed and my stepfather was forced to leave the country, crossing borders in order to look for a bit of that American dream and improve our situation. My stepfather is also an engineer, a fine professional with an exceptional resume. Even so, he was underpaid and eventually found himself unemployed. Also there was the question of being an immigrant and especially being Cuban, which made things a little more difficult.

JC: Did you consider going by land, through the Darién Gap, northbound to the U.S.?

AK: I considered it a lot and, well, I did not do it because I did not have enough money to pay a coyote and make the crossing. Without a doubt I would have done it without thinking about it but the circumstances of life did not allow me to fulfill that dream. It was nothing more than that, a dream.

JC: What have you been up to since returning to the island?

AK: I study computer engineering at the Universidad de Holguín “Oscar Lucero Moya.” At the same time I started a pastry business, Yomi’s Cake, with my girlfriend, Claudia. Over the years she became my wife. The truth is that we are doing well.

JC: What are your plans for the future?

AK: Go to the United States, work hard, prosper as an entrepreneur, and enjoy my freedom in every way.

JC: Is there anything I didn’t ask that you would like to respond to?

AK: Well, I really don’t know, tell me…? My regards, brother!

Postscript

Following my interview with Adrian it was my turn to answer a pertinent and astute question. Asked by CovertAction Magazine’s managing editor Jeremy Kuzmarov to “explain”—how could I reconcile the contradiction between Adrian’s second-to-last response and the context of my opening essay, I conceded, in my own way, to Turkewitz’s closing statement in the CBS Sunday Morning news report. Not only is it true that “the American dream dies hard” as she stated but “even after…all of the problems that one knows exist in the United States—the power of the American dream, it’s powering that journey through the jungle” known as the Darién Gap. According to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, more than 2.76 million undocumented immigrants crossed from Mexico into the southwest U.S. last year. The total crushed the previous annual record by a whopping one million people. And the caravans keep coming.

What I’ve seen and heard in parts of the proverbial “backyard,” places like Ecuador and Brazil well over the past decade, people across the region and beyond who come to South America to embark on that journey northbound is that it’s primarily, but not exclusively, a question of economic desperation. Most migrants simply want to better provide for themselves, their children and families. Within that sincere desire comes the more malignant but easily digestible aspect of U.S. soft power—which is not so soft in terms of migration—Hollywood imagery and messaging, media ad educational propaganda, Disneyland, concepts of freedom and liberty, almost unquestionable bedrock mythologies promoting the “land of the free” abroad.

I ask myself: Would it be any more difficult or dangerous for migrants across the globe to blaze trails to China’s border in search of a better life and financial stability as opposed to crossing the Darién Gap en route to the United States? One attraction over the other remains potent, continuing to capture the minds and imaginations of migrants and others for specific reasons. Again, desperation and destitution, in no small part present and exacerbated in the region and elsewhere due to an ongoing imperialist, colonial-minded global order speak much louder than what I write about. Enough to keep migrants caravanning towards that mythological border separating Mexico and the U.S. is a dream alone. The historical, sociopolitical, and day-to-day societal implications as to why that is, in many ways, demand the insight and analysis of those who’ve made that treacherous journey and experienced firsthand the struggles and hardships, maybe even the loss of a close family member or friend along the journey but certainly not dreamers, trying to survive in the United States.

Reconciling the contradiction(s) concerning reason(s) for why people risk life and limb to make it to the states is always open for debate. To what extent they’re able to reconcile them without the real-life experience of living there, who am I to say? Their motivations for wanting to migrate, I’ve heard them time and again, so often that I refrain from discussing geopolitical issues with most would-be migrants, preferring to let them be while sympathizing with their plight and journey and wishing them well.

Quite noticeable, however, is the transformation from their baseline perception of how their lives will dramatically transform, always for the bigger and better, prior to reaching the U.S. compared to their reflections and complaints about their experiences some years after the real life experience. Many include mundane, daily life struggles and complications. I’ve yet to meet or know of a migrant who became a millionaire entrepreneur or anything of the sort. Tallying the risks involved, problems in the U.S., and moving away from developing their own societies (the brain and people drain syndrome), nothing slows down the migrant caravans and boats.

For those migrants that I know who made it to “America,” many if not all of their expectations prior to arrival have diminished, some more drastic than others. Some have even called “America” quits and moved on or are preparing to do so. I await to read their stories.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com

Great/important work and analysis!

Based upon some redundancies and variations in language, I suspect that there’s a mis-edit in these paragraphs below, from just prior to the Interview portion:

“But there was another story, one that I knew of and, unsurprisingly, had received no press attention. It’s the story of Adrian “Kuba,” a young Cuban who had lived in Ecuador for seven years. At 14 years of age, he had emigrated from the Caribbean island with his parents in search of opportunities abroad. However, seven years later, at twenty-one, Adrian packed his own bags, not to embark on a journey through the Darién Gap en route to that mythic border northbound—not to say the thought had not entered his mind—but to return to his homeland of Cuba to complete his studies and start a new life.

However, seven years later, at twenty-one, Adrian packed his own bags, not to embark on a journey through the Darién Gap en route to that mythic border northbound—not to say the thought hadn’t entered his mind as “the American dream dies hard:—but to return to his homeland of Cuba to complete his studies and start afresh.”