New Doc Curiously Commemorates the Greatest Whodunit in American History

This November 22 marks a grim milestone: The 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy in Dallas.

JFK’s liquidation has left an indelible scar on the psyche of America, one that has arguably never healed.

Compounding the loss of the youthful, handsome president with liberal leanings are enduring, unanswered questions about what is likely the greatest “whodunit” in American history.

Theories abound as to who really whacked Kennedy—from the Warren Commission’s whitewash about a “lone gunman” to the absurdly ricocheting “magic bullet” mumbo jumbo to conspiracies involving organized crime, disgruntled anti-Castro gusano zealots, U.S. intelligence agencies (or a combination of all of them), and so on.

Given this historic date, it’s inevitable that creatives would commemorate the bloody date in various mediums. For example, on October 25 and 26, Theatre 40 in Beverly Hills staged a reading of Oswald—the Actual Interrogation, directed by Louis Fantasia. (See review here)

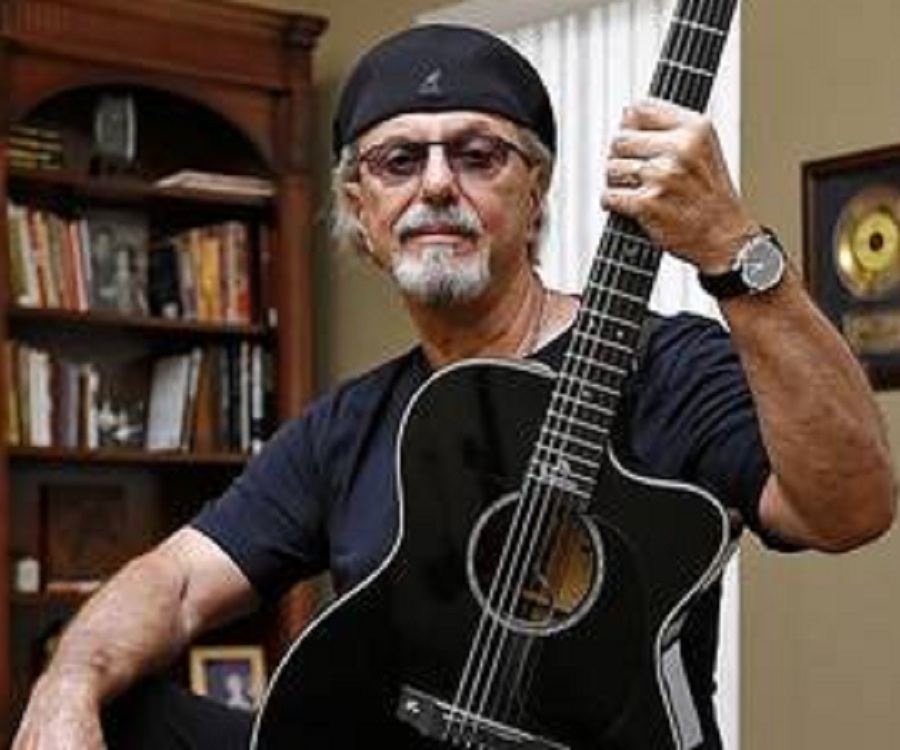

[Source: Photo Courtesy of Dennis Richard]

According to press notes, Dennis Richard’s play is: “Based on the bristling and explosive actual interrogation of Lee Harvey Oswald by Dallas Chief of Homicide, Captain William J. Fritz, the play brings one of the most engrossing battles ever brought to the stage, as a defiant 24 year-old, tight-lipped young man goes up against the best homicide detective the Dallas Police Department had to offer.

“There were no stenographic notes, video or audio tapes of the interrogation, just handwritten notes that Captain Fritz later presented to the Warren Commission.” After the dramatization, Glenn Bybee, an expert on Kennedy’s murder, spoke to theatergoers.

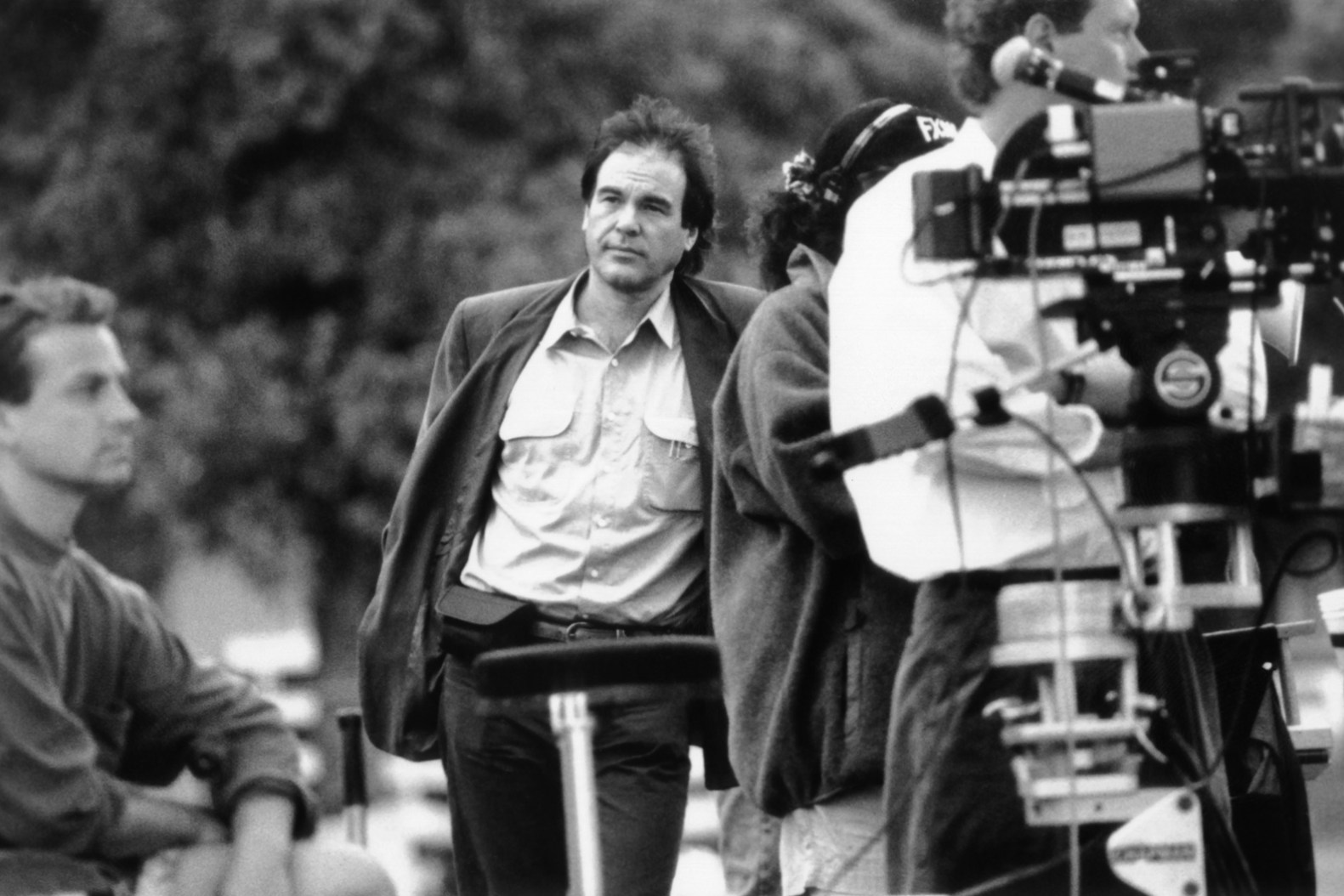

Speaking of those with expertise on the elimination of President Kennedy, according to a press release, “A documentary series about three-time Oscar® winning filmmaker Oliver Stone and the making of JFK, his landmark motion picture about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, is in” the process of being made (apparently it won’t be released until well after the 60th anniversary of JFK’s homicide). “Citizen Stone hails from Sirk Productions writer/director Kristian Fraga, Academy Award® Winning producer John Battsek for Ventureland, and Emmy Award® Winning producer Marc Perez, also producing for Sirk.”

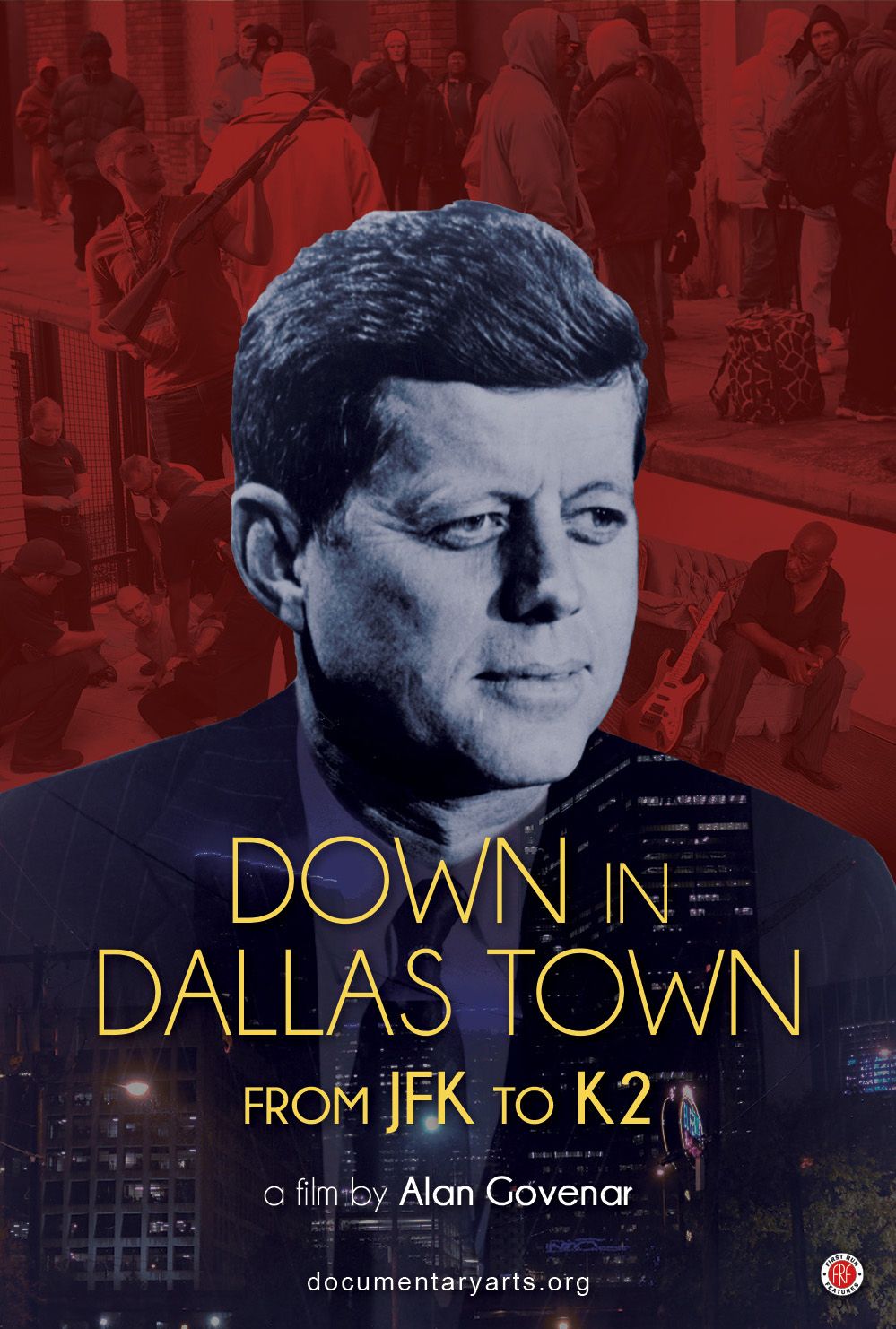

However, a relevant documentary that was released five days before the 60th anniversary of the tragedy at Dealey Plaza is Alan Govenar’s Down in Dallas Town, From JFK to K2. Press notes describe Govenar as “an award-winning writer, poet, playwright, photographer, and filmmaker” and references “the shifting terrain of public memory” regarding the traumatizing event in 1963. Vis-à-vis Down in Dallas Town I think the operative words here are “poet” and “memory.”

Although this nonfiction film is composed entirely of actuality, whether it be from archival footage, news clips or original material, Govenar—who has written many books of poetry (see: https://www.docarts.com/artist_books.html)—has an extremely eclectic, idiosyncratic take on Kennedy’s death and matters he somehow believes pertain to that bloody deed and how it is remembered.

In other words, Govenar is no mere chronicler of events and figures in the traditional documentarian mode, like, say, Robert Flaherty registering Nanook of the North or Moana of the South Seas on celluloid in his far-flung 1920s black and white epics, or Basil Wright and John Grierson following the special train delivering Night Mail to Scotland in 1936, or Ken Burns meticulously chronicling the buffalo or Civil War in PBS nonfiction series, and so on.

The cliché most associated with JFK’s shooting is that everybody of a certain age remembers where he/she was when hearing the startling news and what they were doing, six decades ago.

Govenar explores this sensibility in Down in Dallas Town, plus what the lingering ramifications of losing the purportedly liberal-leaning president then are for society today. Having said this, Govenar’s 73-minute-film starts in a conventional way, with eyewitness accounts of the shooting by people who were present November 22, 1963 at Dealey Plaza.

Most notable is an original interview Govenar conducted with bystander Mary Ann Moorman in 2013 (when that Q&A was originally released and was lensed at, literally, the scene of the crime in Dallas).

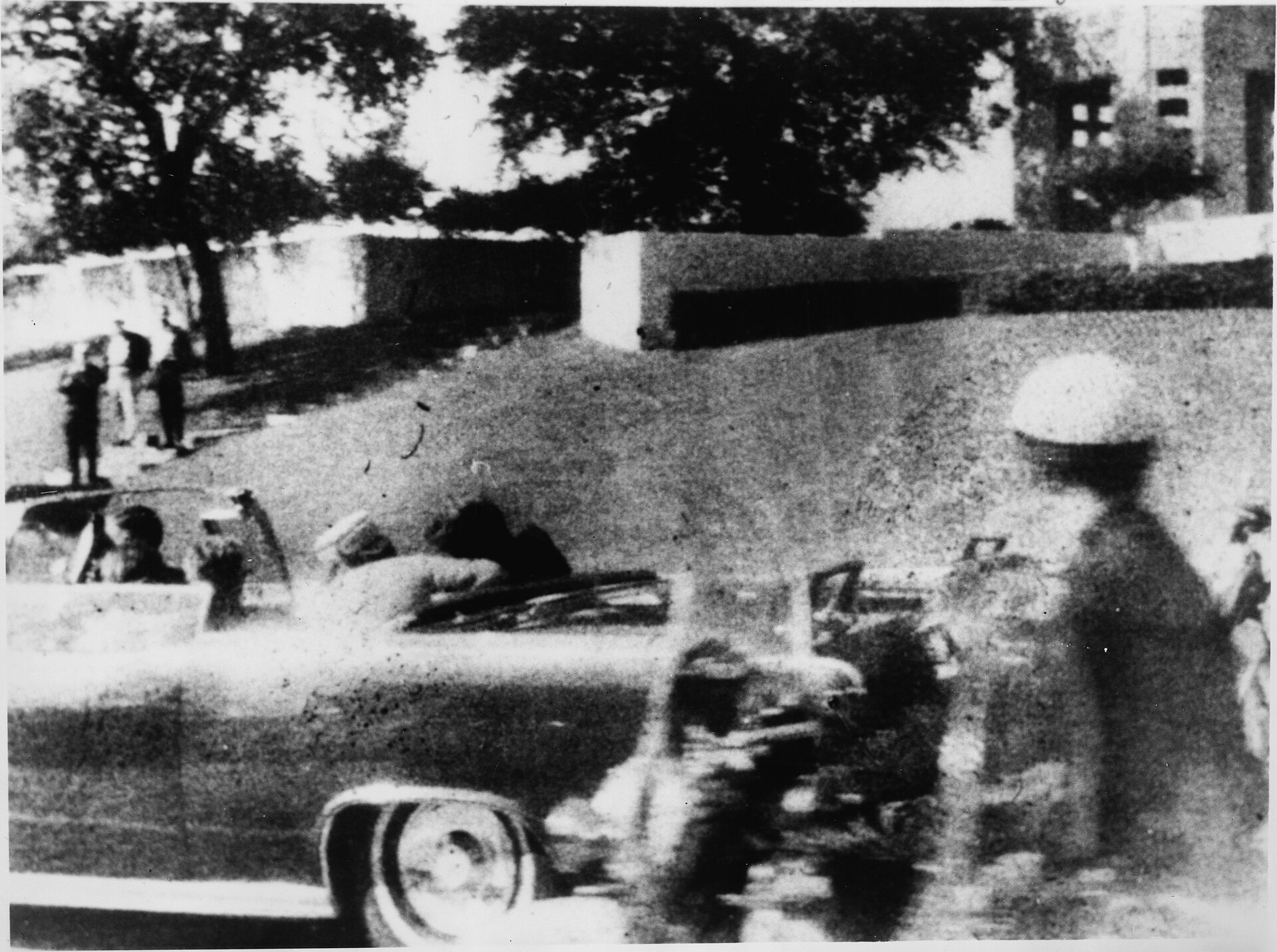

I had, of course, heard of the Zapruder film, but never knew about Moorman’s Polaroid picture of JFK snapped on or about the exact moment he was shot. The white-haired, then-80-ish woman, who had mostly remained silent in public about what she saw and witnessed until then, broke her silence to reveal her recollections of that terrifying experience to Govenar in 2013, and are reprised here.

Brian Wallace, who curated the Manhattan-based International Center of Photography, which presented a 2013 show featuring photos of Dallas on November 22, 1963, states that JFK’s assassination “had a profound effect on American society and on photography… The most significant photos were taken by amateurs, bystanders,” not by professional shutterbugs, Wallace insightfully notes in Govenar’s doc.

Moorman’s singular photograph was the crown jewel of the exhibition entitled “JFK: A Bystanders View of History,” which had commemorated the 50th anniversary of America’s murder most foul.

In Moorman’s photo, clearly visible behind the president’s open-air limousine is the fabled grassy knoll, which many so-called “conspiracy conspiracists” contend is where other snipers fired upon Kennedy—and not just from a sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository Building, where Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly opened fire from, according to the Warren Commission’s “official” account.

But for the most part, Down in Dallas Town tellingly doesn’t pursue this line of thought, although an American tourist to Dallas insists that “the CIA killed” the 35th president. A man identified as Mr. Pike adds: “The story that came out isn’t true. There was a conspiracy,” meaning that Oswald didn’t act alone if, indeed, he was even involved—after all, he didn’t live long enough to stand trial, let alone be convicted of the crime—who knows who the man/men behind the curtain, “the wizard of OS-wald,” really was/were?

But in his motion picture pastiche, Govenar has other fish to fry. Instead of cracking the case like a latter-day Sherlock Holmes or, for that matter, Jim Garrison, to find out whodunit, Govenar focuses on the variety and number of period songs that were composed, recorded and distributed to memorialize the murder of the youngest man ever elected U.S. president.

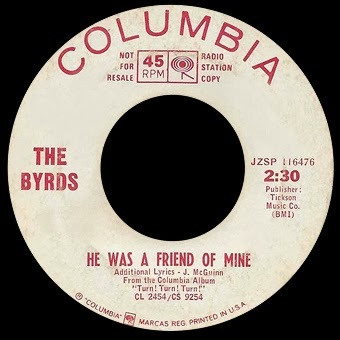

The records were performed in a number of musical genres, including blues, gospel, calypso and norteño, a type of regional Mexican music with the words sung in Spanish. The most prominent of these pieces is actually played by a rock band, The Byrds, which rewrote and repurposed a traditional folk ballad with a changed melody and updated lyrics referencing JFK’s killing.

The Byrds included guitarist David Crosby and vocalist Roger McGuinn, and their cover of “He Was a Friend of Mine” was included in the group’s 1965 album, “Turn! Turn! Turn!”

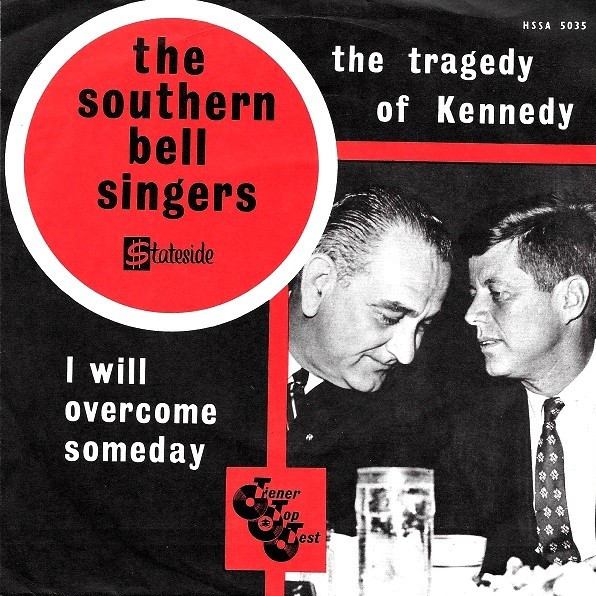

Most of the other musical lamentations of grief in Down in Dallas Town are by obscure artists, such as the Southern Bell Singers, who recorded the bluesy “The Tragedy of Kennedy” in 1963 (on the flipside is a more R&B sounding single entitled “I Will Overcome Someday”). The lyrics include the words, “He went down in Dallas, Texas,” which may be from whence Govenar derived the title for his offbeat documentary.

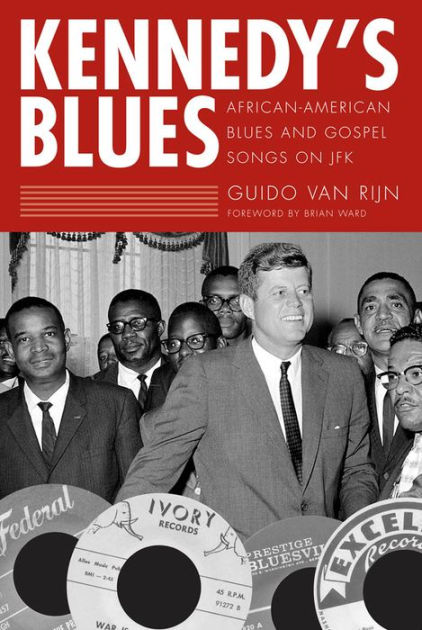

Another gospel inflected song by The Sensational Six of Birmingham, Alabama, is aptly titled “The Day the World Stood Still,” and it is included in the book and musical collection Kennedy’s Blues: African American Blues and Gospel Songs on JFK, by Guido van Rijn, who is interviewed in the film at Haarlem, Holland. (For the entire list of songs, which BTW includes Bo Diddley’s “Khrushchev” (!), see here)

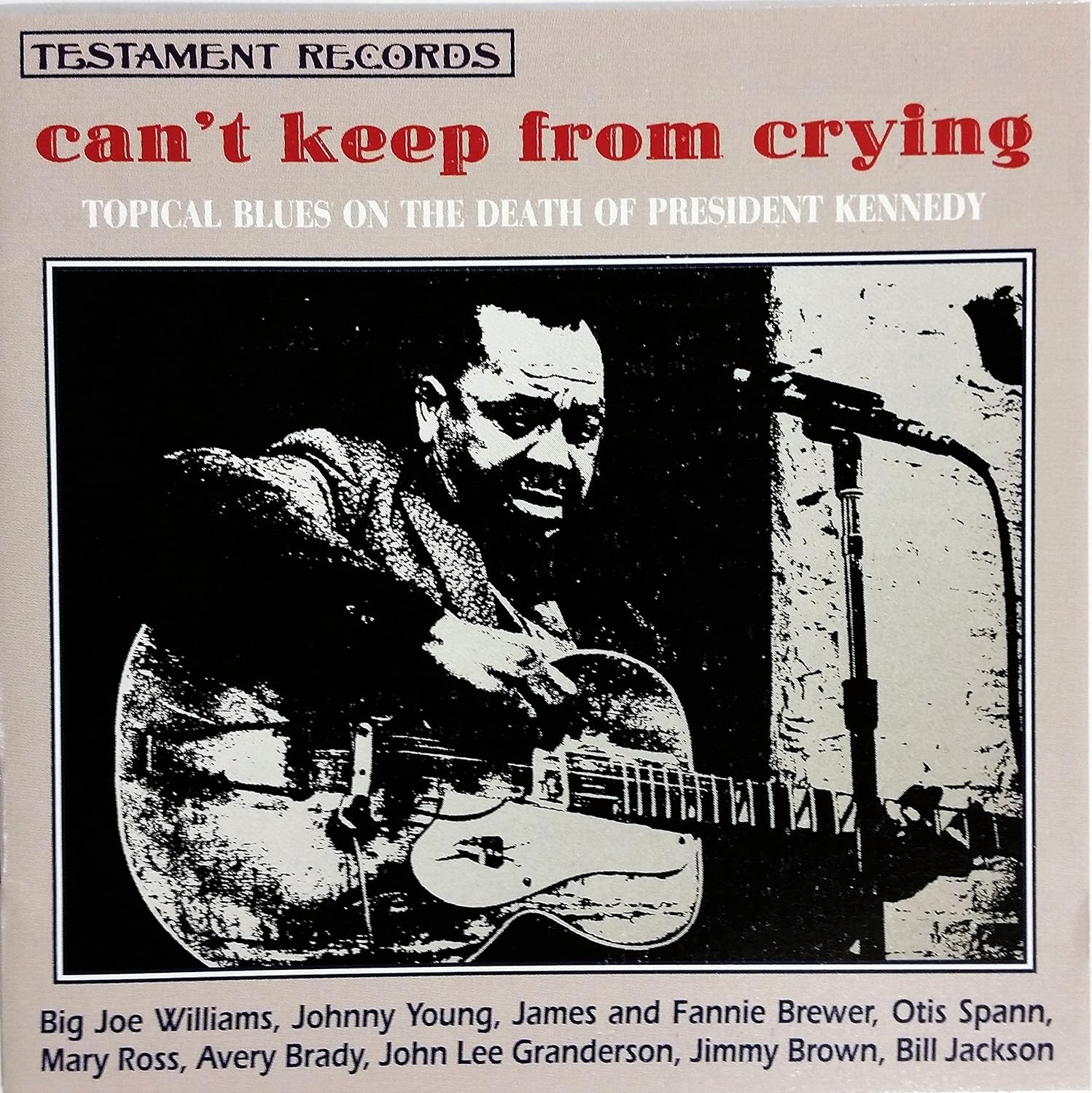

Although he was Dutch, van Rijn repeats a common refrain, that the election of the first Catholic U.S. president resonated deeply with him, because he was raised Roman Catholic. Also depicted is an album entitled “Can’t Keep From Crying: Topical Blues on the Death of President Kennedy,” with numbers by Big Joe Williams, Otis Spann, Mary Ross James and Fannie Brewer, (whoever they were). For details see here.

Throughout the film Govenar cuts or dissolves from a 45 RPM record bearing the title of one of the many songs being performed to the same color photo of a youthful, vigorous-looking JFK. Although many of these songs sound heartfelt, I can’t help but wonder if some were produced to cash in on the public’s grief and fascination with the Kennedy mythos and the president’s shocking death.

And even if the musicians are sincere, many of their songs aren’t particularly good. To my untutored ear, some of the Mexican songs sounded like mariachi knock offs. In one especially cringeworthy scene, an elderly Texas musician named Dorothy Elliott plays her piano and sings along with her middle-aged son, lamenting: “I wanted the world to know how sorry we are he was killed in Dallas.”

The most bizarre thing about Govenar’s catalogue of songs mainly by little known or unknown artists (with the exception of The Byrds) is the strange fact that the most famous of these John Kennedy-related compositions, first recorded by Dion DiMucci, is the plaintive, soulful “Abraham, Martin and John.” Dion was a doo-wop sensation and huge rock star in the 1950s and 1960s, with hits such as “The Wanderer” and “Runaround Sue.” “Abraham, Martin and John” was a big hit on the pop charts, and subsequently covered by major stars, including: Marvin Gaye, Kenny Rogers, Ray Charles, Wilson Pickett, Harry Belafonte, etc.

Yet this JFK-related folk-rock ballad is never so much as even mentioned, let alone played in Down in Dallas Town. What an odd omission in this musical homage to the slain chief executive. To paraphrase the lyrics: “Anybody here seen my old friend Dion? Can you tell me where he’s gone?”

But the most head scratching thing about Govenar’s triptych are sequences dealing with homelessness, gun control and substance abuse. These scenes are interwoven with the film’s eyewitness accounts, ruminations by tourists paying homage to Kennedy by visiting Dealey Plaza, archival footage from JFK’s supposedly stirring inaugural speech (“Ask not…,” etc.) and the Zapruder film, plus all of the mediocre musical interludes featuring JFK-related recordings.

What is the point of these vignettes about the eponymous K2 (a particularly virulent, vicious drug), people living out on the streets, gun buyback campaigns and so on?

It seems to me that Govenar is suggesting that by snuffing out Kennedy and his supposed brand of idealistic liberalism, that America made a wrong turn away from a liberal welfare state toward a harsher dog-eat-dog world, unleashing gun violence, drug addiction, and a growing homeless crisis.

If this is the case, Govenar is not alone in believing that JFK was a reformer who aspired to change the USA for the better, and his death cut short not only Kennedy’s life but the altruistic promise of Camelot.

Oliver Stone, who is arguably the greatest challenger to and scourge of the status quo’s coverup regarding who shot Kennedy and why, certainly thinks that the 46-year-old intended to disengage the U.S. from Vietnam and that cutting him down in his prime enabled America’s deepening entanglement and escalation in Indochina, with tragic consequences.

The reality of Kennedy’s politics and policies is beyond the scope of this review and I’ll leave it to others to assess whether John Fitzgerald Kennedy would have ended homelessness, drug abuse and gun violence had his life not abruptly ended that sorrowful day back in 1963, and if he had lived and run for and served a second term…

According to press notes, writer/director Alan “Govenar’s film, Stoney Knows How, based on his book by the same title about Old School tattoo artist Leonard St. Clair, was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and was selected as an Outstanding Film of the Year by the London Film Festival.

“His documentaries The Beat Hotel, Master Qi and the Monkey King, You Don’t Need Feet to Dance, Tattoo Uprising, Extraordinary Ordinary People, Myth of a Colorblind France and Looking for Home are distributed by First Run Features. Govenar’s theatrical works include the musicals Blind Lemon: Prince of Country Blues, Blind Lemon Blues, Lonesome Blues (with Akin Babatundé), Texas in Paris, and Stompin’ at the Savoy.”

Alan Govenar’s curious movie mélange, meditation and memory of JFK, Down in Dallas Town, theatrically opened November 17 at Cinema Village in Manhattan. The film will be streamed on platforms such as Apple, Amazon, etc., starting in Spring 2024.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ed Rampell is an L.A.-based film historian and critic who also reviews culture, foreign affairs and current events.

Ed can be reached at edrampel@gte.net.