“This pact exists throughout Brazil. It’s not privileged to Rio de Janeiro. Truth be said, it’s a very organic, structured relationship between Rio de Janeiro politicians, militia groups and the police.

How does it function?

Militias control growing amounts of territory. Approximately one million to 1.9 million people (in Rio de Janeiro) reside under the dominion of militia groups that control these territories. They also control how people vote to elect representatives to parliament or state congress or the legislative assembly or even federal congress.

Once politicians are elected, they’ll seek to place their representatives within the executive branch, otherwise, within Rio de Janeiro’s government. That’s to say, we have elected parliamentarians chosen by militia groups. They in turn nominate allies, their cronies, to assume positions within the public security apparatus.

This is what I call the heart of darkness…By controlling territories, they (militias) control how people vote. Consequently, they can offer votes to politicians who participate in this alliance.

Similarly, politicians defend the interests of militia groups by affording them political positions…like in the public health care or social security sector. Criminal factions and militias benefit this way because they don’t exist, exclusively, by means of coercion or the imposition of force or violence. They also exist by being able to provide benefits to poor communities.

This is what I refer to as the organic alliance between the police, militias and politicians, as well as the so-called crime bureau, which is tasked with eliminating those who run afoul of these criminal associations. They have captured the better part of Rio de Janeiro’s state government and its public security apparatus.”

Raul Jungmann, Brazil’s former Minister of Defense and ex-Minister of Public Security

Word on the Streets

“We’ve always had dialogue with left-wing governments, however, we haven’t been able to halt the state’s machine gun by one single centimeter.”

—Débora Maria da Silva (coordinator and founder of Mães de Maio)

Word on the streets, at least in some corners, is: What Brazil really needs is a “revolutionary government.” Any resolution(s) to Brazil’s “heart of darkness” that lingers short of a “revolutionary government” must be weighed against the forces outlined by Raul Jungmann.

His comments were made in respect to the abrupt end to the Marielle Franco homicide investigation, an inquiry that resulted in the detention of a sitting congressman (Chiquinho Brazão), his brother and audit court adviser (Domingos Brazão), and an ex-police chief and former director of Rio de Janeiro’s Homicide Division (Rivaldo Barbosa), as the masterminds and financiers of the hit.

By comparison, and taking into account the recent first and second-round approval of Bill 2.234/2022, a proposal to legalize casinos and other forms of gambling, by Brazil’s congress and the senate’s Constitution and Justice Commission, Jungmann could have been describing a prelude to Havana in the 1940s and much of the following decade.

An eyebrow raiser for Brazil’s establishment left, calls for a “revolutionary government,” one that preceded Luíz Inácio Lula da Silva’s third presidential term, is prefaced by a clear and detailed identification of centuries-old internal issues and whose lives are at stake in the struggle between the country’s past and whatever future it holds. Last year (2023), Brazilian police forces killed 6,393 people. Of the total number of victims, 82.7% were people of African-descent, despite this majority group making up just over 50% of the population. Also last year, over 69% of Brazil’s 850,000 prison population were black people.

In total, 46,328 people were killed across Brazil in 2023. “Approximately 3% of the world population reside in Brazil, however, the country is responsible for roughly 10% of all homicides committed on the planet”, said Renato Sergio de Lima, president of the Brazilian Forum of Public Safety.

The report also revealed that in six cities, Brazilian police forces killed more people than armed gangs and criminals last year. Those cities include Angra dos Reis and Niterói (Rio de Janeiro); Itabaiana and Lagarto (Sergipe); Guarujá (São Paulo); and Jequié (Bahia).

Yanomami and Other Indigenous Nations

Yanomami Indigenous nation remains engulfed in a humanitarian crisis. It resulted in the deaths of 363 Yanomamis in 2023. Casualties, including infant deaths from preventable causes, exceed the number of deaths recorded during former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s last year in office (2022), which reached 343 fatalities. The deaths are the result of an invasion by thousands of illegal gold miners, loggers and land prospectors upon Yanomami nation.

In December, Brazil’s parliament passed Law 14.701, the infamous Marco Temporal (Time Marker). The measure prohibits government-authorized demarcations of Indigenous territories that, for whatever reason, were unoccupied by Indigenous people on the day Brazilian lawmakers ratified the country’s 1988 Constitution.

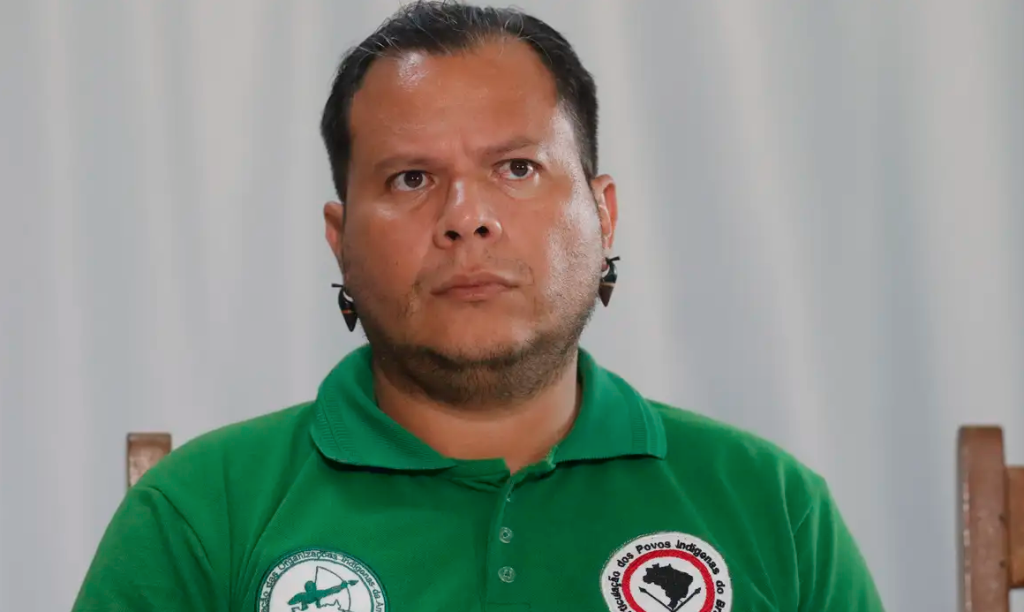

“We support this government; however, we’re well aware that it’s a joint administration, one that’s not 100% aligned with our demands,” said Kleber Karipuna, coordinator at the Articulation of Indigenous People of Brazil (APIB), the largest Indigenous organization in the country. “There are government ministers opposed to certain Indigenous agendas. Dialogue remains open but the outlook will be one of greater demands.”

At this year’s 20th anniversary of Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Encampment), an annual event where Indigenous nations gather in Brasilia to demand their rights, Lula was not invited, as he was in previous years.

Apart from and potentially more damaging than the Time Marker law, is bill, PEC 59. The proposal aims to transfer the role of demarcating indigenous territory from Brazil’s executive branch to the legislature. For Karipuna, the move would signal “the end of demarcations” altogether. “Even worse, it even runs the risk of rescinding indigenous territories already certified (by the government).”

At this year’s 20th anniversary of Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Encampment), an annual event where indigenous nations gather in Brasilia to demand their rights, Lula was not invited as in previous years.

Right-Tide over Pink

With the political bar and Brazil’s international image lowered to basement levels during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency, Lula’s return as head of state has proven good. It has triumphed over lawfare, foreign right-wing interest groups providing moral and financial support to Lula’s political rivals during the 2022 presidential race.

The former Trump adviser and founder of Breitbart News, Steve Bannon, stated the election represented the “second-most-important election in the world,” adding confidently, “Bolsonaro will win unless it’s stolen by, guess what, the machines.” The media mogul has maintained close relations with Bolsonaro’s son and congressman, Eduardo Bolsonaro, since 2018, designating him as representative of his conservative international movement in Brazil.

The government is going to have to “learn how to cope with the ascension of the far right,” Finance Minister Fernando Haddad said earlier this year. In an apparent response, Lula stated that, “instead of reading books,” Haddad should “spend more hours in Congress” lobbying on behalf of government proposals and policies.

Two Grave Institutional Problems:

The melodramatic breakthrough into the not-so-shadowy figures behind Marielle’s assassination could not have come at a more opportune moment. Similar to the popular saying, “Um negócio pra boi dormir” (“to lull the bull to sleep”), comes another aphorism: “para o inglês ver” (“for the English to see”). Both sayings refer to when somebody, a group of people or an entity, says something—not necessarily a lie—to give a warped account of reality. Magically, they transform—like Brazil from slaveholding colony, to empire, to republic—criminality of the highest order to something more respectable. It was Brazil’s former Minister of Finance, Ruy Barbosa, who ordered all of the country’s official archives and documentation related to chattel slavery to be burned on December 14, 1890. In the official statement, Barbosa argued that the government was compelled to make “the last vestiges of slavery disappear,” thus obligating officials to “destroy” the archives to maintain the “honor of the country.”

A Dedicated Right-Wing Military

Antiquated red hysteria is an ideological mainstay for Brazil’s armed forces. In an effort to clean house of untrustworthy military authorities operating within the executive branch, Lula relieved dozens of Institutional Security Office (GSI) officers of their duties following the January 8, 2022, attacks in Brasilia. The organization is responsible for the security of the president, vice president, and their official workplace and residence.

Lula also sacked general Júlio César de Arruda as head of Brazil’s armed forces. The move, according to an unnamed source in Brazil’s military high command, caused “disaffection” within the company.

Despite personnel removals, “The government remains hostage to the military,” says historian Priscila Brandão. “Our biggest problem involves the 1979 amnesty law and its interpretation by the supreme court in 2010 when it accepted the military’s interpretation. The military maintains an effective veto (against any charge of crimes against humanity during the dictatorship or revisions to the amnesty law) ever since the transition to democracy in 1985. While the mere possibility of discussing crimes committed by the dictatorship doesn’t exist in this country, nobody believes punishment will exist.”

A Spy vs. Spy Ring

More than a year into his third term as head of state, Lula sacked Alessandro Moretti as deputy director of the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN). His removal came one week after Brazil’s federal police launched Operation Close Vigilance, which cited Moretti as a suspect in their investigation into an illegal “counterintelligence” cell operating within ABIN. The web is accused of targeting opponents to Bolsonaro, his sons and close allies.

Popularly known as the “Parallel ABIN,” the spy ring formed during the previous government and is accused of tapping the mobile phones of at least 30,000 people, including congressional and senatorial representatives, supreme court justices, journalists, lawyers, police officers and others.

A Crossroads?

Yesterday’s meal doesn’t calm the child

(Boasting of past successes will not resolve today’s problems) — African proverb

Brazil’s pink tide success story during Lula’s first two terms as president are undeniable. Millions were lifted from poverty. The country was removed from the UN hunger list. A thriving, more equitable economy emerged. Quotas were afforded to Indigenous and African-descent people to attend universities, just one of the many institutions they’d been historically excluded from. So on and so forth. However, if one single Bolsonaro term can reverse the gains of 13.5 years of progressive governance (Lula and his presidential successor Dilma Rousseff, both members of the Workers Party) as quickly and thoroughly as it did, then the pink tide should have turned blood-raging-red by now. But it hasn’t. And the chips keep rolling against their hope for a return to the days of old.

Having assumed control of the Argentinian and Peruvian embassies in Caracas following Venezuela’s recent presidential election, Brazil’s foreign policymakers are being pushed to the test in a political row extending beyond regional geopolitics. Them on August 8th, Lula, acting in diplomatic reciprocity, expelled Nicaragua’s ambassador to Brazil, the Honorable Fulvia Patricia Castro Matu. The source of tension derived from Lula’s discussions with Pope Francis and the Vatican’s Secretary of State, Pietro Parolin, over imprisoned catholic priests and bishops in Nicaragua. Also notable was the absence of an official Brazilian delegation at the 45th anniversary celebrations of the Sandinista Revolution on July 19th.

On-the-ground in Venezuela is Celso Amorim, special advisor to president Lula. The mission for Brazil’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs and ex-Minister of Defense is to keep lines of communication between Nicolás Maduro’s government and the opposition open and help reach a consensus between both parties. However, with a Brazilian pink tide divide over the affair (a divide that weakens their hand and benefits the right), home to a military that frowns heavily upon Venezuela, and a right-wing dominated media constantly insinuating or calling Lula a communist, socialist, and/or Chavista sympathizer, is it any wonder why Brazil’s leadership straddles the fence best they can?

Meanwhile, internal issues in Brazil have not thawed from one executive administration to the next. Last month (July), Rio de Janeiro’s state government unleashed a massive police incursion into ten favelas in the city’s west zone. It involves approximately 2,000 military and civilian police, as well as special forces. The operation, scheduled to go on indefinitely, is stated to “bring an end to the war between drug=traffickers and militias,” according to governor Cláudio Castro. “It’s an area where we know the CV (Red Command – the main armed rebel group in Rio de Janeiro) has been attempting to reclaim territory from the militias.”

Earlier in July, a police operation into the City of God favela in Rio resulted in the deaths of six people.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com

Lula wants to maintain a stable relationship with Venezuela so he has been very careful and diplomatic in his comments about Venezuela.

“I think Venezuela is living under a very unpleasant regime,” Lula said, adding that he did not, however, consider it a dictatorship.

“It’s different to a dictatorship – it is a government with an authoritarian slant but it isn’t a dictatorship the likes of which we know so many in this world,” said Brazil’s president.