Private interests and foreign influence helped to pave the path toward Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-1985). The armed forces is not an institution separate from society…It’s a reflection of that violent and authoritarian society. However, they are more dangerous because they have the prerogative to legally use firearms.

—Priscila Brandão

An Interview with Priscila Brandão, author of They Are Illegal and Immoral: Authoritarianism, Political Interference and Corruption Throughout Brazil’s Military History

On March 31, 1964, Brazil’s home-grown, foreign-supported military coup began. President João Goulart (Jango) had not abandoned the country, as was falsely announced by Senator and congressional leader, Auro Moura Andrade; Rather he retreated to the state of Rio Grande do Sul after a failed attempt to rally support against the armed takeover.

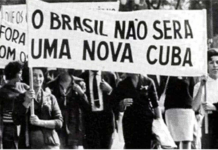

Lock, stock and barrel with the coup plotters, O Globo, Brazil’s largest media conglomerate both then and now, was left virtually unscathed by two decades of ensuing round-ups, torture, forced disappearances, and assassinations; indeed, the paper championed the unfounded, foreign concept of a “domino effect” extending from the shores of revolutionary Cuba to the South American giant and other regional countries. Meanwhile, dictatorships mushroomed across the continent to stave off communism. So did Operation Condor.

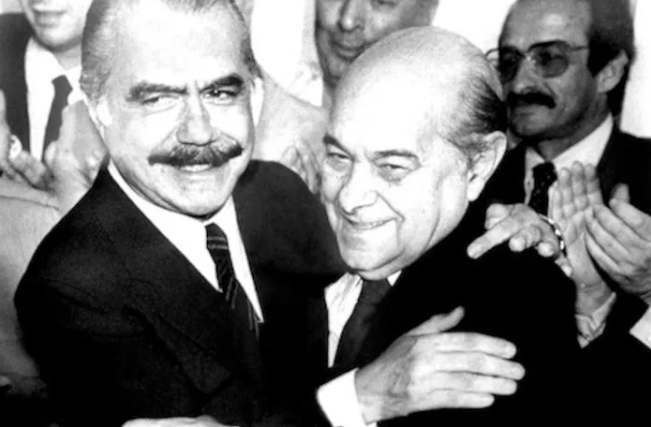

In place of Jango’s government, an administration that proposed modest economic and agrarian reforms, came 20 years of strong-arm military rule, along with the military police which persists across Brazil to this day. Traditional Brazilian political history teaches that civil society movements, not to mention underground resistance organizations, rendered the weakening of the dictatorship, forced democratic presidential elections, and reclaimed democracy. The end process saw Tancredo Neves elected (via an electoral college) president in 1984.

However, just one day before assuming office, Neves was hospitalized. Thirty-nine days later, after seven surgeries and other medical procedures, Neves died on April 21, 1985, from what was eventually reported to be stomach cancer. Coincidence or not, one day after Neves’s death, his butler, João Rosa, died after being hospitalized for 16 days due to poisoning. While this fueled doubts over Neves’s official cause of death, added misgivings loomed in light of his presidential replacement, Congressman and ex-governor of Maranhão José Sarney. At the time of his swearing in, Sarney held a military post, not to mention his staunch, long-standing support for the military rulers he was slated to replace.

Awash in favelas, ghettos, landless rural workers, and oppressed Indigenous nations, such as the Guaraní-Kaiowá and Yanomami to name a few, the idea of Brazil’s “re-democratization” in 1985 was debunked long ago. Last year (2023), for example, Brazilian police killed 6,392 people, 82.7% of whom were Black people. In six cities the police killed more people than armed gangs and crime.

Do Brazil’s security apparatus and intelligence agencies function, by and large, as they did during the military dictatorship? To gain more insight, I reached out to public security specialist and historian Priscila Brandão, author of They Are Illegal and Immoral: Authoritarianism, Political Interference and Corruption Throughout Brazil’s Military History. This book has not been translated into English. Brandão’s work focuses on the South American country’s military dictatorship, military history, federal police, secret services and the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN). She coordinated Brazil’s first Specialization Course on Intelligence and Public Safety, and served as a consultant for the federal government and various state administrations to develop intelligence and security policies. Here are excerpts from that interview.

JC: What was the impetus of your interest in the areas of intelligence and state security?

During my university studies I started researching the military’s repressive system and practices. I then turned my attention to a specific group called the Group of Eleven, which was organized by Congressman Leonel Brizola at the end of 1963 to resist the possibility of a coup. From there I completed my master’s degree at the Federal Fluminense University, where I studied with Professor Maria Celina D’Araujo. She selected me to undertake research about the closure of the SNI [National Information Service]. I recorded testimonies from military personnel as part of a groundbreaking project of the CPDOC. I even interviewed former [military] President Ernest Geisel, a trifecta figure due to his involvement with the “years of lead,” the coup, and the re-democratization process. Being from Belo Horizonte, I made contact with Marco Aurelio Cepik, a lecturer at Minas Gerais Federal University (UFMG). He worked with intelligence services from a public policy perspective and was completing a Ph.D. with a focus on intelligence service reforms in the United States. My contact with Marco transformed my work profoundly because I started to focus more on the ABIN rather than the SNI, as well as reflecting about the intelligence apparatus as it relates to public policy. Since 1998, I have worked a lot with Marco Aurelio. Today he is the director of the ABIN.

JC: Re-democratization is a keyword in Brazil’s political and educational affairs. Apart from the conspiracy theories, how do you analyze what happened in 1984/85 with the re-democratization process and the rise of José Sarney, a man who held a military post and supported the military dictatorship, to the presidency?

Re-democratization is a strong term. Just the other day we discussed this issue…during a meeting here at ABED [Brazilian Association of Defense Studies] in Belo Horizonte. We were discussing Guillermo O’Donnell’s statement that authoritarian processes have ended. Well, that doesn’t mean re-democratization. We’ve never went through—rather, Brazil’s never had a democracy in the strictest sense. Ever since the end of the Brazilian Empire at the end of the 19th century to the establishment of the republic, what was created was not a democracy. They established a liberal government that completely concentrated powers and fomented inequalities…I don’t think we can speak about democracy in the strictest sense. Our democracy is more delegating. In no way does it have anything to do with Sarney.

JC: How does the military exert influence and even power over present-day Brazilian politics?

Think about the power of Leônidas Pires Gonçalves [Minister of the Armed Forces during Sarney’s presidency] and what the military did concerning the constitutional process. All of the lobbying they did. Honestly, considering the other questions you’ve asked, the military’s had an articulation capacity that derives from the constituent assembly period. Their representation capacity is absurd within the legislative branch. They even have representation at the municipal level, within the assemblies, congress, and senate…Their interference is immense. They also control many things. For example, at the ABED, an organization that we academics established to hold public discussions, they [military representatives] came along, opened their own section while knowing everything we intended to research, and refused to provide us space. They are completely against civilians fomenting any type of discourse or developing teaching materials for military training. Their level of control and dressage is absurdly complete.

In Brazilian politics they [the military] have veto power. At the end of 2023, three of my former students, all of whom are pursuing Ph.D.s, and I published an essay discussing the military’s authoritarianism within the Brazilian republic… We’ve never had a democracy. At its limits, our democracy is always conditioned to the interests of the military. They can put on the brakes at any moment. They are the limit. If the power of the president always stumbles before the autonomy of the military, then we can’t speak about democracy. As you can see, President [Luíz Inácio] Lula [da Silva] did not allow any public [or governmental] processions critical of the 1964 coup. Why not? To appease the military. It is a reflection of military politics, including what happened on January 8 [2022, when Bolsonaro supporters attacked the three branches of government in Brasília]. So they [the military] still have plenty of power. Lula is completely pressured by them.

JC: Did the National Truth Commission, established in 2011 to seek answers, justice and reconciliation for criminal acts committed during the dictatorship, fulfill its mandate?

The National Truth Commission [NTC] was an entirely late response [to the military dictatorship]. As you see, Chile, at the end of its dictatorship, albeit much more tied down and conditioned compared to Brazil, instituted their truth commission much sooner. Brazil’s NTC cannot legally try anybody. So our transitional justice [re-democratization] is incomplete.

This past week, during a debate at the ABED, Cepik and I participated in the release of a two-volume book about the [Brazilian] republic and the military. It was organized by Professor Lucas Rezende [UFMG] and Celina D’Araujo…I wrote about intelligence activities within the military. We said that while we don’t bring an end to the liability left by the dictatorship, while the military does not submit to transitional justice or admit to their wrongdoings during the dictatorship, Brazil will never have an efficient intelligence agency. Why? Because the military believes it must keep an eye on the MST [Landless Workers Movement] or spy on a soldier who lives in a favela to ascertain if he is involved in “drug-trafficking.” A poorly resourced [intelligence] agency, as long as ABIN continues spending funds on matters it does not need to, it will keep neglecting its actual purpose. It must be efficient. So, if the intelligence agency is really going to be intelligent, its work must be directed toward its real purpose.

Why does [former Brazilian President Jair] Bolsonaro have so much appeal and fertile soil here? Because our society is authoritarian, violent and racist. There is no acknowledgment that the military operates contrary to how it is supposed to. That is why people believe: Oh well, that person who got beat up was not beaten up so badly; not so many people were killed; a good thief is a dead thief. It has a huge impact on our society. The NTC did not fulfill what it needed to fulfill. It should have investigated further. It should have uncovered more. The NTC is just the beginning, not the end. It failed to do many things.

JC: What is the Parallel ABIN and how are the investigations going?

There is no such thing as a Parallel ABIN. For example, if today, during Lula’s administration these people were operating, then you could say there is a Parallel ABIN. However, as these people operated during Bolsonaro’s government, it is not parallel. Numerous federal police were assigned to ABIN and they operated under the command of ABIN’s former director, Alexandre Ramagem. Ramagem was subordinated to [former Secretary of Institutional Security] Augusto Heleno. Ultimately, Heleno was subordinated to Bolsonaro. So it was not a parallel organ. It was ABIN operating legally, operating with legal technology for which it had no mandate. There is nothing parallel about it. What must be understood is that the ABIN of today has nothing to do with this. Investigations are proceeding and many people are who had nothing to do with this are being investigated. Among staff there is a state of utter frustration, melancholy, discredit and a sense of devaluation even though ABIN’s school, personnel examination and training processes, operational definitions, missions, and a separation between its internal and external sectors are undergoing radical structural reforms.

I can tell you that I have seen a revolution because Marco Cepik is heading the agency now…He has studied intelligence operations for over 30 years, traveling to China, India, United States, Britain. He has operated in various sectors and he has brought forth all of our criticisms and proposals, about professionalism, institutionalism and transparency. It is quite impressive to see the transformations he has made this year. Just having reformed the intelligence doctrine is impressive. I spent two years attempting to reform the public security intelligence doctrine, coordinating with various military personnel, some of whom served as part of the dictatorship. I could not make any advancement. The current public security doctrine is a product of the military dictatorship’s National Security Doctrine. However, the doctrine ostensibly published by ABIN and is publicly available is completely different. It is a phenomenal advance and I really hope it influences the public security intelligence system.

JC: In 2013, it was revealed that the U.S. government spied on former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, some of her top advisers, and Petrobras. Has ABIN or another intelligence agency implemented counter-intelligence measures to thwart such activities?

The U.S. government has always done this. At times they do it conspicuously, other times not so much. For example, the DEA and CIA have operated within the federal police and the CDO (Operational Data Center) for years. The CIA financed the installation of 15 CDO centers where every last computer was furnished by them. By claiming they wanted to test an officer’s degree of trustworthiness, the CIA used a polygraph test to evaluate federal police officers at the CDO. In fact, they used these polygraphs to test a person’s level of obedience or malleability when given orders by the CIA. For years they financed these offices in Brazil.

The safeguarding of knowledge not only in terms of patents but also organic security is of great concern to ABIN. They host many awareness campaigns in these areas. However, ABIN’s budget is minuscule and since it is an organization that is being discredited more and more, whenever the government wants to cut spending, it cuts ABIN’s budget. That is a big problem.

JC: What is the solution?

It is difficult because you are not sure what comes first, the chicken or the egg. ABIN must produce positive effects that are visible to society. This work is currently under way. However, it is taking place precisely when ABIN is at the peak of a crisis in which the media are constantly looking for reasons to discredit the agency based on what happened during the previous administration. So, ABIN is experiencing a positive moment while, simultaneously, receiving bad media coverage. Unfortunately, this is very bad. If you interviewed me a year and half ago, of course, I would have said shut down ABIN, during Bolsonaro’s administration. That was a mafia.

The law that created ABIN is bad. A decree was recently passed which better regulates ABIN. However, there is no chance to even attempt to change the actual law because, with Brazil’s overloaded, right-wing congress, the situation can only worsen. It would be foolhardy to submit ABIN’s legislation to a rewrite because congress is dreadful.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com