U.S. democracy-promotion institutions were key to destroying any hope for democratic development in Haiti after the Cold War.

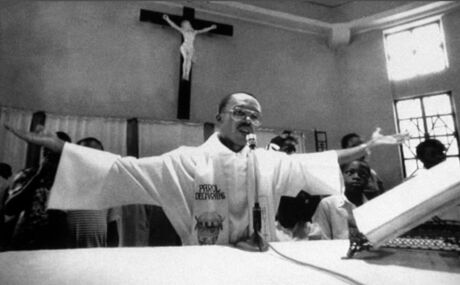

In 1986, when popular uprisings kicked out the nearly 29-year-long dictatorships of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc,” the U.S. could have become a partner to improve liberty and prosperity in Haiti. Instead, the U.S. backed some of the most oligarchic and anti-democratic forces in the country even after a popular movement peacefully voted in a progressive Catholic priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

U.S. Colonialism in the Western Hemisphere’s Second Republic

Haiti became the second post-colonial country in the Western Hemisphere after African slaves, inspired by the slogan of liberty, equality and fraternity proclaimed by the French Revolution, rose up for their freedom and human dignity. After a bloody struggle that included multiple attempts by the French and their allies to commit genocide against the slaves and ship in new ones from Africa, Haiti won independence by 1804.[1]

The U.S. and Haiti might have become partners advancing some of the highest ideals of classical liberalism, promoting anti-colonial, constitutional, and even democratic, governance against European capitalist imperialism. By the time the two republics were established, however, those ruling the U.S. had developed their own imperial ambitions and white supremacist ideologies arising from centuries of colonialism and African chattel slavery.

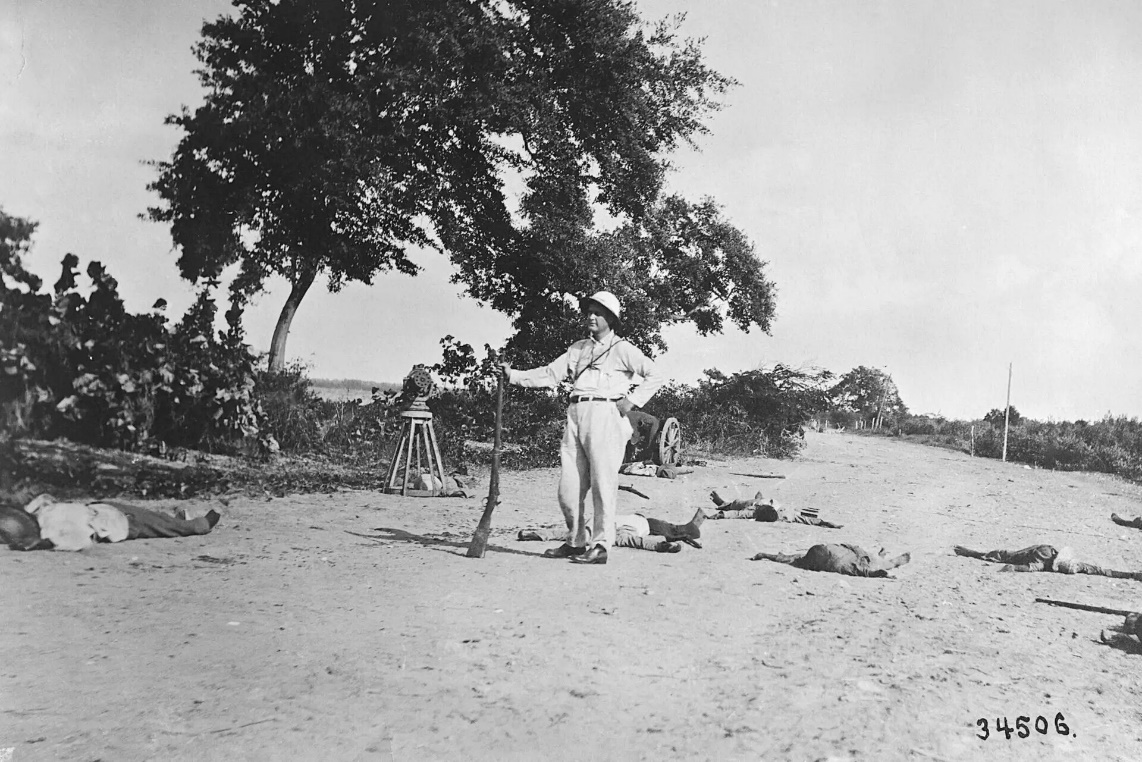

When Haiti declared independence in 1804, the U.S. under President Thomas Jefferson, a slave owner, refused to recognize the new country. The U.S. would not establish official diplomatic relations with Haiti until 1862 during the U.S. Civil War. U.S. intervention in Haiti culminated in the 1915 to 1934 invasion and occupation. Over those 19 years, the U.S. Marines set up a forced labor system, opened up Haitian land to foreign ownership, and seized Haitian banks.

Before the occupation officially began, eight U.S. Marines disguised in civilian clothes and brandishing guns robbed the Haitian central bank in broad daylight and stole Haitian gold reserves for the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank) to house in its vault on Wall Street.[2]

The U.S. set up the Haitian Gendarmerie, forming the nucleus of the Armed Forces of Haiti that would dominate Haitian politics in brutal fashion until President Aristide disbanded it in 1995.

Future anti-imperialist critic Smedley Butler was the first commander of the Haitian Gendarmerie and, in June 1917, he led his gendarmes to force the Haitian parliament to dissolve itself, impose a State Department-written constitution opening up Haitian land to foreign ownership, and cover up any written record of the coup.[3]

U.S. Fails to Establish Neocolonial “Democracy”

The 1986 uprising that forced President Jean-Claude Duvalier to flee Haiti, popularly known as the Dechoukaj (“Uprooting” in Haitian Creole), might have been an opportunity for the U.S. to truly foster democratic development abroad. The Reagan administration had just proclaimed in 1983 a new foreign policy paradigm of democracy promotion and established its crowning institution, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

On its face, democracy promotion promised to move U.S. foreign policy away from support for dictatorships in the name of anti-communism and toward supporting democratic development in all countries regardless of any corrupting interests. In reality, the NED and U.S. democracy promotion were established to promote the economic and security interests of the U.S. government, corporations, allies and transnational capitalism.[4]

While the Haitian military ruled Haiti from 1986 to 1990, NED and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) linked up with or created civil society organizations and networks disproportionately dominated by light-skinned mixed-race Haitians, and black elites. The U.S. spurned the more radical democratic grassroots movements popularly known as Lavalas (“Flood” in Haitian Creole) that consolidated around Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a Salesian Catholic priest and proponent of Liberation Theology.

This is a key strategy of U.S. democracy promotion, to link with foreign elites organically amenable to U.S. capitalist interests and promote them as democratic leaders while marginalizing working-class democratic movements. If a country has popular organizations advancing the rights of workers, women, minorities, journalists, or students that the U.S. deems too left-wing or too friendly (or even neutral) toward its geopolitical adversaries, the U.S. will simply create or boost different organizations and leaders more to its liking.

In Promoting Polyarchy, perhaps the most influential critical book on democracy promotion from a U.S. scholar, William I. Robinson writes that U.S. democracy-promotion attempts to establish neo-liberal capitalist rule by consent (that is, through nominally representative electoral procedures rather than open dictatorship). But the U.S. resorts to force when attempts to establish consent fail, and Robinson named the 1991 coup against Jean-Bertrand Aristide as a particularly egregious example of this.[5]

During the 1990 presidential elections, the U.S. chose Marc Bazin, an official of the World Bank and former finance minister under Baby Doc, as its favored candidate. USAID spent $10 million on the elections, supporting Bazin and rallying elite-based civil society behind him.[6] The U.S.-backed coalition, however, lacked popular support, and Aristide won more than 67% of the vote. Bazin scored less than 15%.

Punishing Haiti’s First Popularly Elected President

By the time Aristide was inaugurated in February 1991, the U.S. had given $26 million in aid to the vehemently anti-Aristide private sector of Haiti, and allocated another $24 million in May 1991 to elite-based political parties and civil society groups through the State Department’s Democracy Enhancement Project. Aristide’s political party and allied groups were largely kept out of these aid packages despite their electoral successes and grassroots support.

Again, if one took U.S. rhetoric at face value, Aristide would seem like a great candidate for U.S. assistance. Aristide was not an anti-American Marxist revolutionary leading a communist party or guerrilla group; he was a reformer who rose up through civil society and grassroots democratic mobilization via constitutional electoral procedures. Yet, Aristide was serious about improving conditions and pursuing justice for the impoverished majority even if it meant impeding the profits and privileges of the Haitian elite and foreign interests.

As Aristide attempted to implement social and economic reforms, the U.S. cut off aid on which Haiti had become dependent over the decades since 1915. The U.S. stated that aid would be reinstated if human rights improvements were met, despite the fact that aid to the previous dictatorships did not include such demands. Aristide and the Lavalas movement did make significant progress in health care, education, disbanding repressive military and paramilitary institutions, and bringing human rights offenders to justice despite Haiti’s dire lack of resources.[7]

Essentially, Aristide and Haiti were punished for doing the very things that the U.S. government claimed to promote. Aristide’s administration was far from perfect, but it is difficult to judge because he was overthrown in a bloody military coup just eight months into his presidency.

Officially, the U.S. condemned the coup and backed Aristide. However, in 1992, the U.S. resumed its Democracy Enhancement Project, funding the same elite anti-Aristide groups that represented key constituencies of the coup regime even while Lavalas democracy movements were brutalized and slaughtered.

Robinson writes that “most of the coup leaders and members of the junta that directly conducted the systematic repression, and the political figures such as [Jean-Jacques] Honorat and [Marc] Bazin that tried to legitimize a post-Aristide order, had since established extensive relations with Washington through the CIA and the DIA [Defense Intelligence Agency], the NED, and other programs.”[8]

The U.S. hoped to create another democratic transition without Aristide, but the intransigence of the coup leaders and resistance of the Haitian masses left little alternative between the continuation of a destabilizing dictatorship, or the return of Aristide.

The U.S. did not act meaningfully to reinstate Aristide until after he agreed to impose a U.S.-approved agenda. Aristide was compelled to implement a “structural adjustment program” of austerity, privatization and deregulation, give more power to the U.S.-backed electoral opposition, and even give amnesty to putschists in exchange for a $1.2 billion aid package from USAID, the IMF and World Bank. In October 1994, the U.S. once more invaded Haiti and reinstalled Aristide, who was only allowed to serve another 16 months because his three-year exile during the coup was considered time served in office.

Covert U.S. Collusion in a Military Takeover

The U.S. openly backed anti-Aristide political groups connected to the former Duvalier regime and the military dictatorships of 1986 to 1990 and 1991 to 1994 as part of a bloody campaign against Haitian democracy.

After the Duvalier dictatorship’s fall, the CIA backed the Haitian military and set up the Haitian intelligence agency, Service d’Intelligence National (SIN), both of which engaged in large-scale drug trafficking. The CIA provided $1 million a year to SIN between 1986 and 1991, during which SIN agents killed up to 5,000 democracy activists and even cancelled the 1987 Haitian election by massacring as many as 300 people as they waited in line to vote.[9]

Robinson describes the military regime of 1991 to 1994 as an “all sided war of attrition against the Haitian people” in which the Haitian elite and military, U.S. policy, and international media and business interests converged.[10]

Raoul Cédras, the military officer who led the 1991 coup against Aristide, was a CIA informant trained at the infamous U.S. Army School of the Americas, where dozens of infamous Latin American death squad, drug trafficking, intelligence and military junta leaders had trained since 1946.

Emmanuel Constant, a founder of SIN who was on the CIA’s payroll, founded the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti in 1993, a death squad that murdered and terrorized Aristide supporters.

Also in 1993, the CIA created black propaganda (propaganda wherein the source is concealed or credited to a false authority) to smear Aristide and sabotage efforts to reinstall him, distributing a later discredited report to U.S. government officials alleging that Aristide was mentally unstable.[11]

Democracy-promotion institutions backed elite sectors of Haitian society even as clandestine U.S. and Haitian interests persecuted popular democracy movements, yet this failed to stem the Lavalas movement.

Aristide and his new party, Fanmi Lavalas (Flood Family, FL), surged into office once more after Aristide won the 2000 presidential vote with over 91% support, more than doubling his raw vote numbers. Yet Aristide would be unconstitutionally thrown out of office once more and, in this anti-democratic coup, democracy promoters would play a much more direct role.

Punishing Haiti for Electing Aristide, Again

The crisis began like many regime-change efforts involving U.S. democracy promotion, with a dispute over elections. As Aristide swept the presidency, FL won supermajorities in the Haitian Chamber of Deputies and Senate, winning all 27 Senate seats. However, the opposition disputed ten Senate seats because the votes were counted in a way that the FL candidates won outright, but the opposition argued they should have moved to a second-round runoff vote.

Polling evidence suggested that many of the FL candidates would have won the second-round vote, and FL would have maintained a clear majority even without any of the ten disputed Senate seats. However, the opposition used the disputed seats as a pretext to delegitimize the entire Aristide FL government.[12]

The U.S. government remained as obstinate as ever toward the first popularly elected president in Haiti’s history. Aristide entered office in February 2001, and the new George W. Bush administration in the U.S. promptly rushed to cut off aid to Haiti once more, and then blocked $615 million in loans from the Inter-American Development Bank that was scheduled to be distributed over a few years.[13]

The U.S. would continue to withhold aid throughout Aristide’s second term even after Aristide ordered the winners of the disputed FL Senate seats to resign, accepted opposition members into his government, and agreed to hold legislative elections years early while reforming the electoral council in favor of the opposition.[14]

U.S. Ambassador Accuses NED Core Grantee of Covertly Organizing Anti-Democratic Coup with USAID Money

In a 2006 documentary, Brian Dean Curran, the former U.S. ambassador to Haiti appointed by President Clinton in January 2001 just before Bush Jr. took office, spoke bluntly about his disputes with democracy-promotion organizations, particularly NED core grantee the International Republican Institute (IRI). The IRI spent $3 million in Haiti from 2000 to 2004, and it was instrumental in uniting hardline anti-Aristide parties into the Convergence Démocratique (Democratic Convergence) in the lead-up to the 2000 elections.

Curran stated that the Bush administration’s official policy, and thus his own diplomatic mission, was to accept Aristide as president and work with him to find political solutions to the political impasse plaguing Haiti, advising Aristide and the opposition to compromise with each other.

However, Curran complained that, through back channels, namely the IRI, the elite opposition received messages from Washington and the State Department to maintain an uncompromisingly hard-line stance against Aristide with the hope of overthrowing his government.[15]

Ambassador Curran accused the IRI program officer in Haiti, Stanley Lucas, of telling opposition leaders that he and his hard-line position demanding regime change, not Ambassador Curran and his stance of peaceful engagement and compromise, truly represented U.S. policy in Haiti. Lucas, the scion of a wealthy landowning elite mulatto family, had been a militant adversary of Aristide for years.[16]

Stanley Lucas’s cousins, Rémy and Léonard Lucas, were arrested in 1998 over allegations by human rights groups that they organized the mass butchery of more than 200 peasants who were protesting for land distribution outside the Lucas family ranch at Jean-Rabel in July 1987.[17]

In the documentary, Ambassador Curran thus claimed that the IRI directly undermined official U.S. policy—to advance dialogue, compromise and cooperation between the government and opposition so Aristide might finish his constitutional term—in favor of an unofficial hard-line policy to remove Aristide and FL, and replace them with the U.S.-backed elite opposition.

Curran cabled his concerns about Lucas and the IRI through official channels to his superiors in the White House’s Latin American policy team, led by neo-conservative diplomats Elliott Abrams and Otto Reich. During the 1990s, Abrams was politically and morally compromised after he helped cover up the 1981 El Mozote Massacre, where at least 800 civilians were slaughtered by the Salvadoran military, and was then convicted of lying to Congress in 1991 about his knowledge of the Iran-Contra affair as Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs.[18]

Reich’s reputation was similarly tarnished after he stepped down as USAID assistant administrator for Latin America and the Caribbean to become a leading propagandist involved in the Iran-Contra affair. Despite this, the neo-conservative-dominated Bush administration named Abrams Senior NSC Director for Democracy, Human Rights, and International Operations in June 2001. It also installed Reich as the top U.S. diplomat in Latin America and the Caribbean as Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs from January 2002 to 2003. Reich then served as Special Envoy to Latin America from January 2003 to June 2004.[19]

As Curran’s boss, Reich refused to remove or censure Lucas, and denied that he was even informed of Curran’s protests despite evidence to the contrary. Reich admitted to The New York Times that Curran failed to see the U.S. policy shift away from support for Aristide. Reich’s statement contradicted U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who emphatically asserted that supporting Aristide’s right to serve out his democratically elected term was the only U.S. policy toward Haiti’s government.[20]

Responding to Curran’s official complaints from the U.S. Embassy in July 2002, USAID banned Lucas from running IRI programs in Haiti for 120 days. However, Lucas continued to de facto lead IRI programs while serving nominally as a translator, which IRI officials acknowledged went against the USAID ban.[21]

The USAID mission director in Haiti in charge of administering funds to IRI and other democracy-promotion groups, David Adams, expressed personal misgivings about Lucas but said that he faced strong pressure from Congress to continue the program. Adams stated that “there were senior State/NSC officials who were sympathetic to IRI’s position as well,” likely referring to Abrams, Reich and another neo-conservative diplomat, Roger Noriega.[22]

In December 2002, Stanley Lucas used USAID money to fly hundreds of opposition members to a training program at the Hotel Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic owned by Cuban expatriates and billionaire sugar and real estate tycoons, the Fanjul family (big-time donors to current Secretary of State Marco Rubio). No members from Aristide’s FL party were invited to this ostensible democracy program.

Two leaders of the budding armed rebellion against Aristide were present at the hotel during the training meetings, but insisted they did not attend the meetings. These rebels were Guy Philippe, a former death squad leader and drug smuggler, and Paul Arcelin, a former government adviser and ambassador to the Dominican Republic during the 1986-1990 Haitian military junta governments.[23]

After the 2004 coup, Guy Philippe said he had known Stanley Lucas since childhood (Lucas was Philippe’s table tennis coach) and that he met Lucas both in Ecuador in 2001 and in the Dominican Republic during the 2002-2003 IRI trainings, but that they did not discuss politics. Arcelin said he met Lucas at the Hotel Santo Domingo to talk “about the future of Haiti” but claimed they did not discuss overthrowing Aristide.

Lucas denied meeting with either of them.[24] Brian J. Berry, vice president of the U.S. Republican Party media consulting firm The Strategy Group for Media and director at the conservative political action committee Citizens United, was among the trainers brought to the Hotel Santo Domingo.

Ironically, the U.S.’s former favored presidential candidate for the 1990 elections, Marc Bazin, was a moderate opposition leader who favored negotiations with Aristide at the time of the IRI-funded Dominican Republic meetings. Bazin gave credence to accusations that the Bush administration was pursuing a covert regime-change agenda while publicly proclaiming engagement and compromise with Aristide and FL.

Bazin stated that representatives of his organization at the trainings told him that “there were two meetings—open meetings where democracy would be discussed and closed meetings where other things would be discussed, and we are not invited to the other meetings.” Others who were invited to the closed meetings told Bazin that Aristide would ultimately be overthrown and that Bazin should stop calling for compromise.[25]

At the time of the trainings, Stanley Lucas kept in close contact with neo-conservative diplomat Roger Noriega. Noriega had worked at USAID under Reagan, where he oversaw so-called “non-lethal” aid to the Contras in Nicaragua (right-wing terrorist group intent on sabotaging the left-wing Sandinista social revolution). In the 1990s, he became a senior staff member of segregationist Senator Jesse Helms, where in 1996 he co-authored the Helms-Burton Act that escalated the U.S. embargo against Cuba.

As leader of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Helms had backed Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier before Aristide’s first election in 1990 and supported Raoul Cédras, the military junta officer who led the coup that ousted Aristide the first time in 1991.[26] In 1994, Helms, referring to a discredited CIA black propaganda report, stated that Aristide was “mentally unstable” and that the U.S. should not attempt to reinstate the democratically elected leader of Haiti.[27]

Noriega, an enemy of Aristide for more than a decade, was the U.S. ambassador to the Organization of American States (OAS) during the 2002 coup against Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. In January 2003, Noriega was nominated to replace Otto Reich as Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, making Noriega the top U.S. diplomat for Latin America during Aristide’s ouster in February 2004.[28]

Fed up with the contradictory actions of the Bush administration that undermined his diplomatic efforts, Ambassador Curran resigned in September 2003 and was replaced by James Foley. With the new Bush-appointed ambassador in Haiti, Aristide’s government only became more fragile.

When armed rebels crossed the border from the Dominican Republic and made their way to the capital of Port-au-Prince, Noriega helped the IRI increase funding to the Haitian opposition, and the White House took a wait-and-see approach to the political crisis boiling over in Haiti.

As the rebels closed in, Aristide tried one desperate last bid to make a deal with the opposition wherein he would give up much of his power. Luigi Einaudi, an OAS representative from the U.S. who brokered the deal, accused the Bush administration, through Ambassador Foley, of “pulling the rug out” from their efforts by canceling the meeting between Aristide and the opposition.[29]

On February 29, 2004, Secretary of State Colin Powell and Ambassador Foley spoke with Aristide and advised him to resign from office to avoid further bloodshed, chartering a U.S. plane to fly Aristide to the Central African Republic. Aristide immediately went public with accusations that he had been coerced into resigning by U.S. officials and that the U.S. had kidnapped him to facilitate a coup against his government.[30]

Two Coups Lay Bare the True Face of “Democracy Promotion”

The case of Haiti is not some aberrant corruption of U.S. democracy promotion via groups such as the NED, USAID, or IRI. It is its true face, unobstructed by the propaganda that so often veils it.

The two coups against Aristide demonstrate stark similarities. Both occurred under the George Bush Sr. and Jr. administrations. Both U.S. administrations and their democracy-promotion organizations showed little support for the only legitimate, popularly elected government and political movement in modern Haitian history. In fact, both administrations actively undermined Aristide and the Lavalas movement in favor of the far less popular or democratic elite opposition.

The Haitian case is essential for understanding imperialist so-called democracy promotion because U.S. anti-democratic intervention and exploitation in Haiti is so brazen. In other countries, such as Venezuela, Serbia or Syria, the U.S. made substantial investments of money and labor in creating plausible deniability and a narrative to support its agenda and obscure or justify its actions. Yet both Bush administrations intervened in Haiti with only the slightest democratic and human rights pretexts and covered up their efforts with a minimal diplomatic and media effort.

The U.S. did not bother to invest in a convincing media narrative for the opposition or against Aristide, relying on silence as well as dubious statements from U.S. government officials in the White House, Congress and CIA to muddy the waters of what was going on. This move illustrates Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s third filter of their propaganda model in Manufacturing Consent, that is, mainstream news’s reliance on “official sources.”[31]

U.S. officials, acting as official sources, issued statements in mainstream coverage of Haitian politics to distort issues related to Haiti’s problems and Aristide’s government without having to substantially invest in a domestic or Haitian propaganda program, as they had with Nicaragua during the Iran-Contra affair. The realpolitik of U.S. imperialism in Haiti since the end of the “Baby Doc” Duvalier dictatorship has been perhaps the most naked of any in the world.

U.S. democracy-promotion institutions became more important for deep political and imperialist intrigue between 1990 and 2004. In this case, it was the NED and USAID’s core grantee, the IRI, led by the right wing of the U.S. political establishment during a Republican administration. This reflects opportunistic use of well-positioned allies by Bush Jr.’s team in Haiti specifically, as well as the increased value of democracy promotion as both a rationale and technique of U.S. intervention in the broader post-Cold War unipolar era.

U.S. policy makers, through their covert intelligence and pseudo-overt democracy-promotion arms, committed grave crimes against Haitian democracy. No Cold War or other threat to U.S. security existed to justify such crimes. Powerful U.S. officials and organizations undermined official U.S. policy and democratic and human rights principles, and democracy-promotion institutions violated their own formal rules against meddling in foreign elections or supporting individuals or groups that undermine democratic processes.

Since the 2004 coup, Haitians suffered a 15-year United Nations military occupation, natural and man-made disasters, the banning of Haiti’s most popular party, Fanmi Lavalas, from contesting elections, and abysmal election turnouts installing governments with no popular legitimacy.

Investigations show that, after Aristide’s election, powerful Western allies of the U.S., namely France and Canada, also colluded in deadly crimes against Haiti that violate basic principles of human rights, international law, and relations between countries.[32] After more than 200 years of independence achieved by the world’s only successful slave revolution, Western powers still refuse to consider Haitians as fully human or forgive them for the crime of freeing themselves.

C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (2nd edition) (New York: Vintage, 1989), 358-60, 370-75. ↑

Jonathan M. Katz, Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022), chapter 11. ↑

Katz, Gangsters of Capitalism, chapter 13; Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), chapter 2; Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti 1915-1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1971). ↑

See Jeremy Kuzmarov, “If the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) Is Subverting Democracy—Why Aren’t Some of the Left Media Calling It Out,” CovertAction Magazine, March 4, 2022. ↑

William I. Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy: Globalization, US Intervention, and Hegemony (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 294. ↑

Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy, 289. ↑

Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy, 295. ↑

Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy, 303. ↑

Kathleen Marie Whitney, “Sin, Fraph, and the CIA: U.S. Covert Action in Haiti,” Southwestern Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas 3 (1996), 319. ↑

Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy, 305. ↑

For more on black propaganda, see Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion (6th ed.) (Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2015), 21. ↑

Peter Hallward, “Option Zero in Haiti,” New Left Review, no. 27 (May-June 2004), 37-38. ↑

Hallward, “Option Zero in Haiti,” 39. ↑

Idem. ↑

Haiti: Democracy Undone, produced by Peter Bull (Discovery Times, 2006), digital, https://vimeo.com/483807153. ↑

Amnesty International, “Amnesty International Annual Report 1999,” Annual Report (Amnesty International, June 14, 1999), 187, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/0001/1999/en/; Max Blumenthal, “The other regime change,” Salon, July 17, 2004, https://www.salon.com/2004/07/17/haiti_coup/. ↑

Due to lack of resources, the Haitian judicial system was unable to carry out an official investigation of the Jean-Rabel massacre. Léonard Lucas was released from prison in January 2003 following orders from Aristide, and Rémy Lucas escaped from prison just hours after Aristide was flown out of the country during the February 2004 coup. See Belleau Jean-Philippe, “Massacres Perpetrated in the 20th Century in Haiti | SciencesPo Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network,” Paris Institute of Political Studies, January 25, 2016, https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/massacres-perpetrated-20th-century-haiti.html; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, “Rapport No 27/10, Pétition 134-02, Décision de Mise Aux Archives, Haïti” (Organization of American States, March 16, 2010), https://www.cidh.oas.org/annualrep/2010fr/Haiti134.02fr.htm. ↑

In 2000, the position of Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs was renamed as the Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs. ↑

George Bush attempted to appoint Reich Assistant Secretary in 2001 but failed due to opposition in the Senate over Reich’s involvement in the Iran-Contra affair and his support for anti-Cuban terrorist Orlando Bosch. Bush made a recess appointment for Reich to become Assistant Secretary for one year without Senate approval, and then named him Special Envoy to Latin America, which did not require Senate approval. ↑

Haiti: Democracy Undone. ↑

Joshua Kurlantzick, “The Coup Connection,” Mother Jones, November-December 2004, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2004/11/coup-connection/. ↑

Walt Bogdanich and Jenny Nordberg, “Mixed U.S. Signals Helped Tilt Haiti Toward Chaos,” The New York Times, January 29, 2006, 10. ↑

Bogdanich and Nordberg, “Mixed U.S. Signals Helped Tilt Haiti Toward Chaos,” 10. ↑

Idem. ↑

Idem. ↑

Max Blumenthal, “The Other Regime Change,” Salon, July 16, 2004. ↑

Haiti: Democracy Undone. ↑

James Dao, “Bush Names Veteran Anti-Communist to Latin America Post,” The New York Times, January 10, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/10/world/bush-names-veteran-anti-communist-to-latin-america-post.html. ↑

Haiti: Democracy Undone. ↑

Constant Méheut et al., “Demanding Reparations, and Ending Up in Exile,” The New York Times, May 20, 2022. ↑

Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (2nd ed.) (New York: Pantheon Books, 2002). ↑

Haiti Betrayed, directed by Elaine Brière (Cinema Politica, 2020), digital, https://haitibetrayedfilm.com/; Méheut et al., “Demanding Reparations, and Ending Up in Exile.” ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ben Arthur Thomason received his Ph.D. in American Culture Studies from Bowling Green State University in 2024.

He specializes in the history, culture, and geopolitical economy of U.S. imperialism and soft power. He has published peer-reviewed articles, including “Save the Children, Launch the Bombs: Propaganda Agents Behind The White Helmets (2016) Documentary and Media Imperialism in the Syrian Civil War,” in The Projector (2022), and “The Moderate Rebel Industry: Spaces of Western Public-Private Civil Society and Propaganda Warfare in the Syrian Civil War,” in Media, War and Conflict (2024).

He is currently seeking to publish his manuscript, Make Democracy Safe for Empire: US Democracy Promotion from the Cold War to the 21st Century.

Get in touch with Ben by going to benarthurthomason.com or by emailing him at benthomason696@gmail.com.