[This article is specially timed for Thanksgiving week and to commemorate native heritage month. See other recent articles on Native-American history published by CovertAction Magazine here, here and here.—Editors]

One of the ugly features of the U.S. Army genocide directed against Native Americans in the 19th century was the systematic slaughter of the buffalo.

Native Americans drew their livelihood from the buffalo by hunting them and using their skins for clothes and other life necessities.

They worshipped them in spiritual ceremonies and considered them to be a vital and sacred aspect of their communities.

In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz wrote: “Everything of the Kiowas [like other Native groups] had come from the buffalo….Most of all, the buffalo was part of the Kiowa religion. A white buffalo must be sacrificed in the Sun Dance. The priests used parts of the buffalo to make their prayers when they healed people or when they sang to the powers above. So when the white men wanted to build railroads or when they wanted to farm or raise cattle, the buffalo still protected the Kiowas. They tore up the railroad tracks and the gardens. They chased the cattle off the ranges. The buffalo loved their people as much as the Kiowas loved them.”

Dunbar-Ortiz continued: “There was war between the buffalo and the white men. The white men built forts in the Kiowa country, and the wooly headed buffalo soldiers shot the buffalo as fast as they could, but the buffalo kept coming on, coming on…Then the white men hired hunters to do nothing but kill the buffalo. Up and down the plains those men ranged, shooting sometimes as many as a hundred buffalo a day. Behind them came the skinners with their wagons….The buffalo saw that their day was over. They could protect their people no longer.”[1]

The horrific history underscores the significance of recent efforts by the Blackfeet Nation in northern Montana to bring back the buffalo to their community.

These efforts are chronicled in a documentary film, Bring Them Home, which was screened in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in late October and premiered on PBS on November 24.

Bring Them Home is directed by brother-sister duo Ivan MacDonald and Ivy MacDonald, as well as Daniel Glick, and narrated by Lily Gladstone, who was nominated for an Oscar for her performance playing an Osage woman who survived the 1920s Osage murders in Oklahoma in The Killers of the Flower Moon (2023).

Gladstone stated that Bring Them Home is “really about not letting that light go out. It’s about healing our relationship with buffalo that colonization hurt so tremendously—restoring that and, in doing so, healing ourselves and that interdependence, that kind of co-healing, that responsibility, we have to bring them back.”

Eloquently capturing the beauty of the Montanan landscape, Bring Them Home starts out by interviewing Blackfeet Nation elders who discuss how significant the buffalo—or “inni”—are to their way of life.

Noting how buffalo bones were used in the past as toys and their fur as bedding, they emphasized how they considered the buffalo to be like one of their relatives.

White settler attacks on the buffalo were in turn designed to annihilate and render extinct the Blackfeet people—like other native groups.

By the end of the 19th century, there were only about 1,000 buffalo left when there had been more than 30 million at one time.

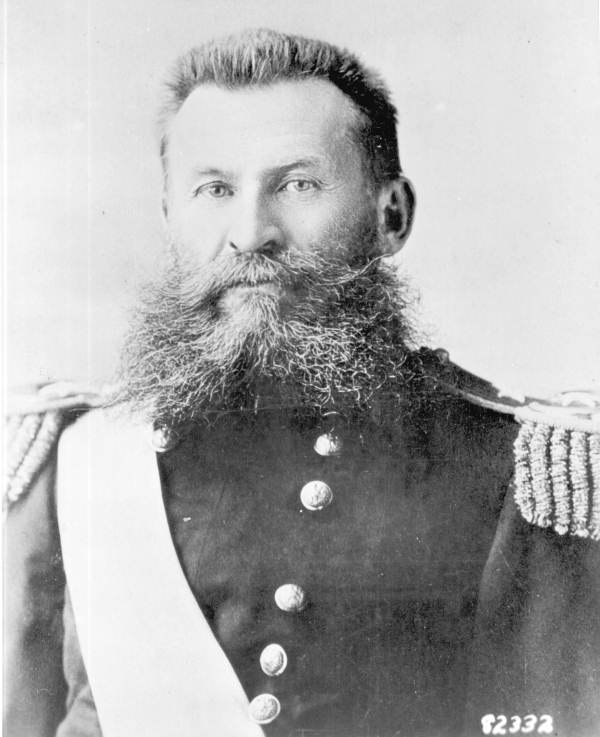

George Crook a famous Indian fighter, wrote to a friend: “The buffalo is all gone and an Indian can’t catch enough jack rabbits to subsist himself and family and there aren’t enough jack rabbits to catch. What are they to do? Starvation is staring them in the face….I do not wonder and you will not either, that when these Indians see their wives and children starving, and their last source of supplies cut off, they go to war. And then we are set to kill them. It is an outrage.”[2]

Much of the dirty work of killing the buffalo was carried out by African-American cavalry regiments—an irony captured in Bob Marley’s famous song “Buffalo Soldier,” which addresses how one oppressed group was used by the white man to subdue another.[3]

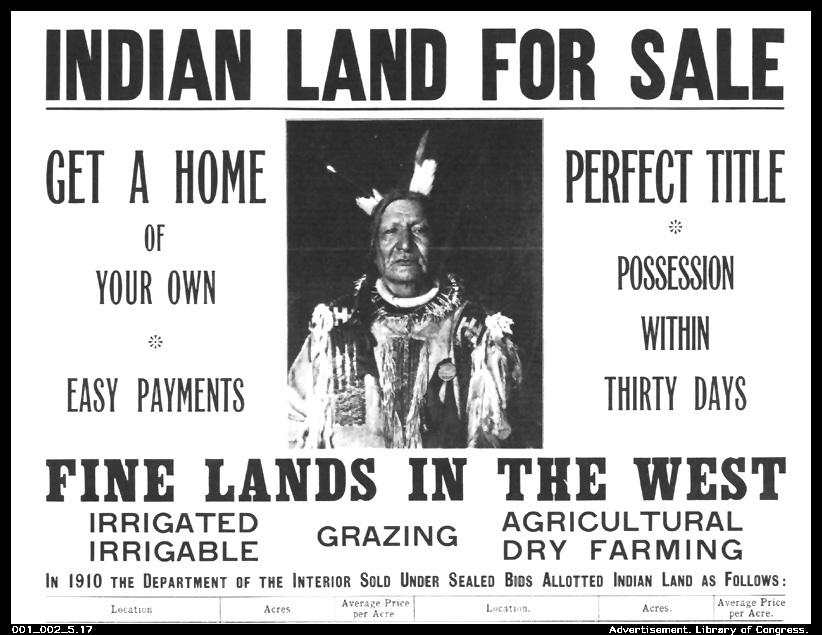

After the Blackfeet Nation was forced onto reservations and cut off from the buffalo, Congress passed the 1887 Dawes Act, which broke up the Blackfeet reservation into small plots of land and further fractured the Blackfeet community.

Government agents subsequently began kidnapping Blackfeet children to send them to residential schools, where they were taught to believe their own cultural traditions were inferior and that they needed to embrace dominant American “values” and to assimilate into U.S. society.

Cut off from their past and with limited means of making a good living, many Blackfeet Nation people fell into despondency and poverty, with high suicide and drug and alcohol abuse rates.

As part of the white man’s effort to eradicate their culture, Blackfeet people could even be sent to jail for speaking their native language.

Blackfeet children continued to play a traditional game called “make the buffalo run” where they would run as quickly as their legs could carry them, hollering at the top of their lungs, as though they were trying to drive a herd of buffalo to a buffalo jump.

One of the key figures involved in the efforts to bring the buffalo back to the Blackfeet reservation, Paulette Fox, first saw buffalo in 1979 when she traveled off the reservation as a university student.

In 2009, Fox and other tribal leaders—including Ervin Carlson and Leroy Little Bear—launched the Inni initiative whose goal was to bring the buffalo back to the Blackfeet community.

The first step was locating and securing ownership of a herd of buffalo that were found in Alberta’s Elk Island National Park.

The Native elders saw that these buffalo were like “orphans who were not properly cared for” like in the old days.

Once the buffalo were brought back, Blackfeet cowboys were employed to corral the herd and teach them new habits. The buffalo came to have a positive impact on the region’s grassland ecosystem and contributed to the flourishing of other animal and plant species.

The buffalo also provided a psychological boost to the Blackfeet community, which now proudly hosts buffalo re-enactment drives for kids as part of an effort to reclaim its cultural heritage.

Though initially local area ranchers had viewed the buffalo as a menace, they ultimately came to realize their value. Youth gained meaningful employment doing the physical labor of looking after the buffalo on a daily basis.

At first, the buffalo had to be kept in a confined area, but the film details the efforts to have them released into the wild, where they could roam around like in historical times.

Since their release in June 2023, the herd has grown from 49 to over 100 and is now thriving.

Bring Them Home suggests that the Blackfeet’s buffalo reclamation project has helped to heal the community and to regenerate its land. It has also inspired other native groups.

At the Tulsa screening of the film, representatives of the local Yuchi tribe discussed a program they had adopted to bring back buffalo to their community outside Tulsa.[4]

The Yuchi established themselves in Oklahoma in the 1830s after they were driven off their ancestral land in Georgia, Tennessee and Florida during Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal campaign. Some of the Yuchi had fought with the Seminoles against the U.S. Army during the Seminole Wars, which lasted roughly from 1816 to 1858.

The buffalo reclamation project is coinciding with efforts to revitalize Native American languages and culture across the U.S. and Canada.

Though the Trump administration has cut off funding for some initiatives that were government supported, tribal leaders are taking it upon themselves to raise funds and sustain programs that are helping Native peoples to reclaim the heritage that was stolen from them.

We may in the coming years see a wide cultural renaissance among Native groups that would be of great benefit to society as a whole.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014), 143. ↑

Charles M. Robinson III, General Crook and the Western Frontier (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), 220. ↑

See William H. Leckie, The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967). ↑

The Yuchi received five buffalo from Denver in 2023. Richard Grounds, the head of the Yuchi language program, stated that the acquisition of the buffalo means “We, the Yuchi People, are still here.” In a Yuchi celebration called the Green Corn ceremony, there is a dance to honor the relationship between people and the bison. The Cheyenne and Arapaho nations have also come to possess buffalo herds. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.