H. Rap Brown was charged for instigating a riot that never took place, and was sent to a Supermax prison after being convicted of a murder to which someone else confessed

[This article is special for Black History Month. See previous CAM articles for Black History Month here, here, here and here.—Editors]

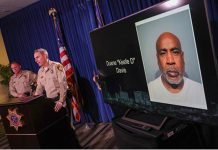

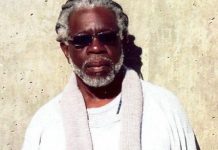

On November 23, 2025, Jamil Abdullah al-Amin, formerly known as H. Rap Brown and one-time chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), died in a federal prison hospital in North Carolina at the age of 82.

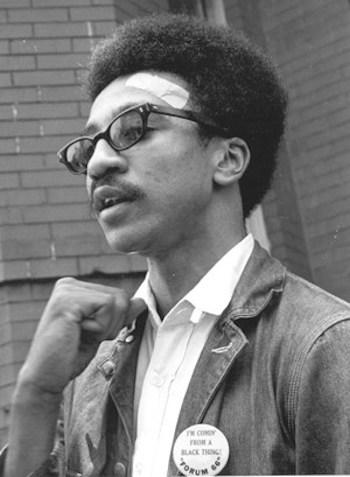

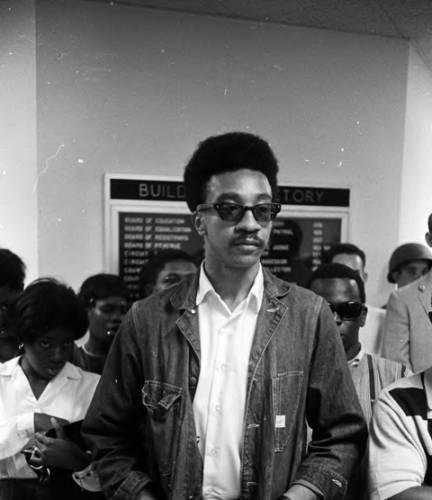

SNCC was a leading civil rights organization of the 1960s. Brown was appointed its chairman in 1967 at the age of 23.[1]

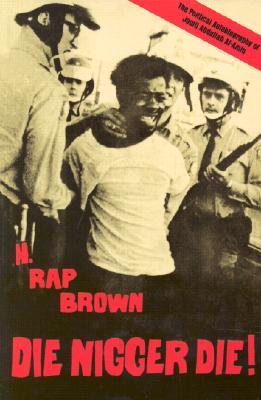

In 1969, he wrote a popular Black Power manifesto Die Nigger Die! which shed light on the systemic racism in U.S. society, including among white liberals, and how its consequences included the development of an inferiority complex among Black people. Brown argued that Blacks were a colonized force in America who should not try to integrate into white society but, rather, should take pride in their own cultural heritage and fight for their liberation.[2]

A proponent of direct-action tactics, Brown had started his activist career organizing a walkout of students at Southern High School in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in solidarity with demonstrations at nearby Southern University, and subsequently joined with activists in the Alabama Black Belt to challenge white supremacy through the ballot box.[3]

Born Hubert Gerold Brown, the name “Rap” was given to him because of the word games that he played with other boys on the streets, demonstrating his command of language, sharp wit and a mature political sensibility.

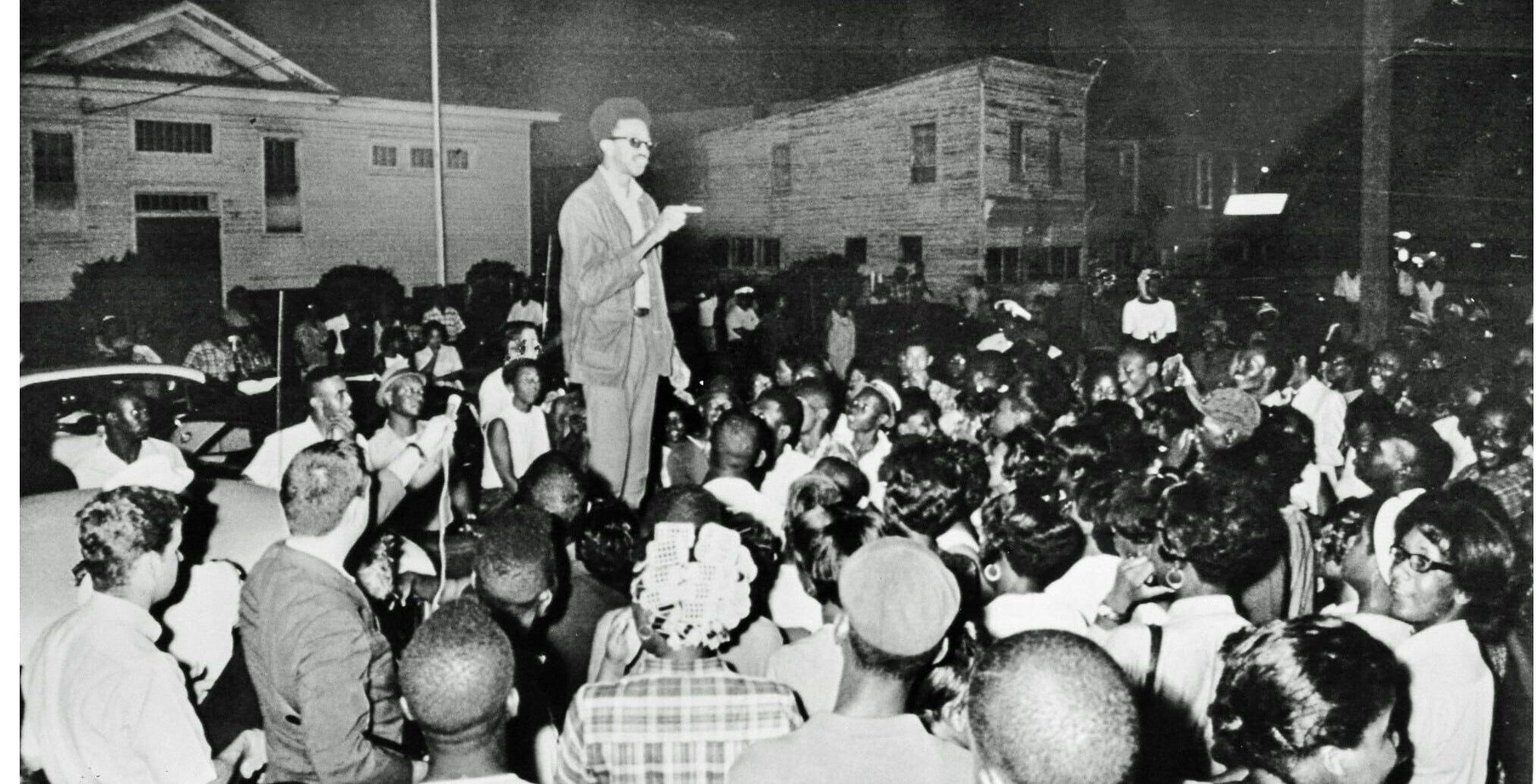

Around the time of the July 1967 Detroit riots that left 43 people dead, Brown became a target of the FBI’s counter-intelligence operation (COINTELPRO) when he gave a speech proclaiming that “Black folks built America, and if it don’t come around, we’re gonna burn America down.”

Brown was suggesting that it was hypocritical for white liberals to condemn Black violence when violence was “part of American culture. It is as American as cherry pie” as he said.

In 1968, Congress passed an anti-rioting law that was used to prosecute leaders of the Democratic Party Convention protests in Chicago. The law was referred to as the “H. Rap Brown Federal Anti-Riot Act.”

A fervent opponent of the Vietnam War and admirer of the Cuban Revolution, Brown was arrested for supposedly instigating a riot in Cambridge, Maryland, in 1967 during which Brown was shot without provocation by a deputy sheriff.[4]

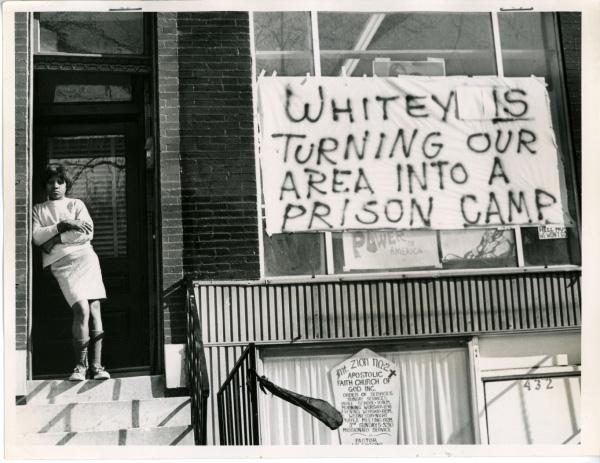

Historian Peter Levy determined that the Cambridge riot never actually took place but that the police chief and all-white fire company allowed a small fire at a school to burn for hours and spread so it would destroy Black businesses and could be blamed on Black militants like Brown—whom Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew called a “mad dog.”[5]

In a speech he gave in Cambridge, MA before his arrest, Brown didn’t promote any violence, but said. “Black folks got to understand that [its beautiful to be black]. We built this country. They tell you you(`re) lazy. They tell you you stink. Brother, do you realize what the state [would] be of this country if we was [were] lazy? That the slaves built this country? If we was lazy how we built this country? (Brother,) they captured us in [from] Africa and brought us over here to work for them. Now, who`s lazy?” Brown continued by noting that “he [the white man] run around and he talks about black people looting. Hell, he is the biggest [greatest] looter in the world. He looted us from Africa. He looted America from [the] Indians. Man can you [How can he] tell me about looting? You can’t steal from a thief. This is the biggest thief going.”

Brown had angered President Lyndon B. Johnson at a White House meeting where Johnson had complained that all-night demonstrations outside the White House were so noisy that his daughters could not sleep. Brown responded by stating that he too was “real sad that the presidential daughters’ repose had been disturbed, but Black people in the South have been unable to sleep in peace and security for a hundred years. What did the President plan to do about that?”[6]

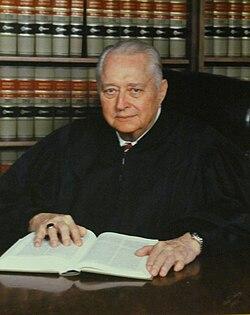

A secret 1967 FBI memo had called for “neutralizing” Brown. After he was arrested on gun and rioting charges that year, a U.S. federal judge, Lansing Mitchell, declared his intention to “get that nigger [Brown].”[7]

In 1970, Brown was placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list after he was falsely accused of detonating a car bomb that killed two of his closest SNCC associates, Ralph Featherstone and William Payne, who were en route to the courthouse where one of his cases was being heard.[8]

Then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was a racist intent on destroying the Black Power movement through COINTELPRO.

COINTELPRO documents placed Brown on a list of four men considered top targets to surveil, harass and destroy. Others on the list included Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King, Jr., whom the FBI conspired to kill.

FBI branch offices devised various plans under COINTELPRO to sow seeds of discord between Brown and other radical Black leaders and to have him arrested on frivolous charges and denied bail.

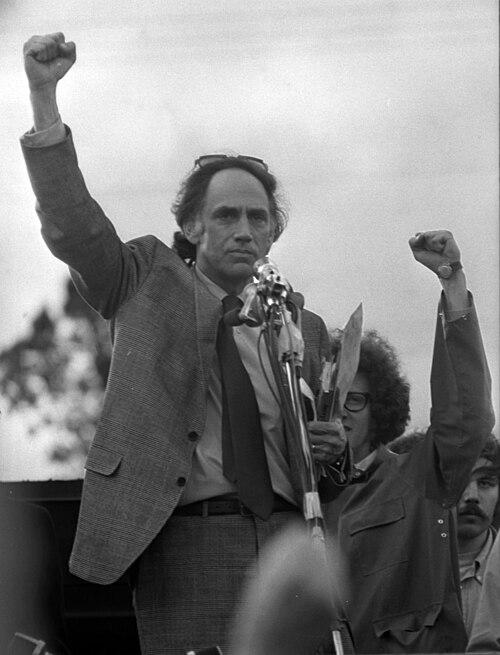

Brown’s lawyer, William Kunstler, stated that the U.S. government had pursued an unabated vendetta against Brown, writing in 1973 that his case “is a classic example of the perverse use of the legal process to silence a voice that some hate and fear.”[9]

In 1971, Brown was wounded in a police shootout in New York, and convicted of robbery and assault.

Brown never actually robbed anyone, but was pursued by New York Police Department (NYPD) officers when members of a group he was working with confronted drug dealers in a bar.

William Kunstler charged that police witnesses concocted a phony account to cover up the fact that they had brutalized Brown. Watergate journalist Bob Woodward found that previous charges against Brown were similarly fabricated.[10]

Brown served five years in Attica Prison during which time he converted to a sect of Sunni Islam and changed his name to Jamil Abdullah al-Amin.

After he was released from prison, al-Amin continued his political activism and fought drug abuse, poverty and gangs in Black communities where he lived in New York and Atlanta, Georgia.

In Atlanta’s West End, al-Amin established his own mosque and grocery store that sold Qurans. Additionally, he became President of the American Muslim Council, the first organization, based in Washington D.C., to promote Muslim issues.

The head of an Islamic civic group in Atlanta called al-Amin “a pillar of the Muslim community.” Nevertheless, the FBI sent paid informants to infiltrate his mosque, according to his New York Times obituary, and tried to continuously set him up for crimes he did not commit.

In 1995, the Times reported that police pressured a man who was shot in al-Amin’s neighborhood into making a false accusation implicating al-Amin. The next year, Al-Amin was arrested on phony drug charges.

Al-Amin’s lawyer said that the police were looking for any excuse to put al-Amin in jail. The FBI had a file on him that contained approximately 44,000 documents.

Al-Amin’s brother Ed told The Nation magazine that his brother was routinely spied upon and harassed by police, “just one damn thing after another. No matter how absurd. The police simply would not leave my brother alone…an ongoing police vendetta.”[11]

In March 2000, after missing a trial call over a contested traffic charge, a warrant was issued for al-Amin’s arrest in Cobb County, Georgia.

When two deputies showed up at his store to serve the warrant, they did not find al-Amin, but James Santos (aka Otis Jackson), another member of the community and leader of a street gang that looked to rebuild communities by driving out drug dealers and violence.

Fearful of being sent back to prison for violating his parole, Jackson exchanged fire with the police when they approached; he was shot and injured, one deputy was killed, and the other injured.

The next day, Jackson confessed to the shooting to his parole officer. That did not stop a federal agent from arresting and beating al-Amin three days later.

Left Voice reported that al-Amin’s trial was rife with insubstantial evidence and contradictions submitted in court: weapons introduced that did not have al-Amin’s fingerprints; a ballistics expert who was later terminated; and the state failing to reveal Jackson’s written confession to the crime.[12]

The surviving deputy’s incident report stated that he had hit his assailant with gunfire and al-Amin had no bullet wounds when he was arrested four days later or gun powder residue on his body. Blood evidence from the crime scene also did not match al-Amin’s and the deputy said that his assailant’s eyes were grey while al-Amin’s eyes were brown.

Al-Amin said that he was at another location at the time of the shooting and that evidence used against him was planted by FBI agent Ron Campbell who had a sordid history of attacking Black suspects, including in Philadelphia where he shot a black suspect in the head.[13]

In a 2002 prison interview, al-Amin told The New York Times that he was framed because the power structure “still fear a personality, a character coming up among African Americans who could galvanize support among all the different elements of the African-American community.”

The FBI continued to perceive al-Amin as a threat in prison because of his mentorship to younger inmates, issuing a report in 2006 featuring discussion about him that was titled “The Attempt to Radicalize the Georgia Department of Corrections’ Inmate Muslim Population,” according to an article in Left Voice.

The report led to al-Amin’s transfer to the federal “supermax” prison in Colorado where some of the nation’s worst criminals are housed and inmates are confined to their cells 23 hours a day.

The transfer represented yet another gross injustice done to al-Amin, whose life story epitomizes the horrific mistreatment of African-Americans in the U.S., including especially those who speak truth to power and inspire others to rise up.

Brown had been introduced to key luminaries in SNCC by his older brother Edward, who went to Howard University with SNCC Chairman Stokely Carmichael. Carmichael called Brown a “serious strong brother” with a “calm, deliberate manner and a presence that inspired confidence.” ↑

H. Rap Brown, Die Nigger Die! (New York: Dial Press, 1969). ↑

Brown’s father Eddie was a World War II army veteran who worked for the Standard Oil Company in Louisiana for 30 years. His brother Ed became president and chief executive of the Southern Agriculture Corp., a non-profit organization helping Black farmers obtain federal subsidies and other benefits historically denied them. ↑

Dustin Holt, “Author debunks riot myth,” Dorchester Star, July 23, 2017. ↑

Holt, “Author debunks riot myth”; see also Peter B. Levy, Civil War on Race Street: The Civil Rights Movement in Cambridge, Maryland (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003). On the night of the riot, Brown gave a speech and then walked a woman home before he was shot. Washington Post columnist Jack Anderson ridiculously asserted, based on what FBI sources told him, that “Peking’s shadow” was behind the riots. Peter B. Levy, The Great Uprising: Race Riots in Urban America during the 1960s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 87. Newspapers across the U.S. condemned Brown for his “hate white” rhetoric and for being what they considered a seditious traitor.

Brown once called Johnson “the greatest outlaw going” and a “two-gun cracker.” ↑

Levy, Civil War on Race Street, 154. Mitchell was from Louisiana. A 1970 book by Eugene Methvin, a Reader’s Digest editor with an Air Force background, warned that Brown and other Black Power radicals whom he considered to be extremists, followed Leninist tactics by instigating riots as the prelude to a revolution. ↑

Levy, The Great Uprising, 112.

Levy, The Great Uprising, 114. ↑

Levy, The Great Uprising, 114. ↑

Al-Amin was picked up by the authorities for questioning after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and later released without a shred of evidence tying him in any way to the attack. ↑

Al-Amin’s son pointed out that state authorities took great measures to depict Otis Jackson as mentally ill and incompetent in an attempt to negate his confession, though in reality Jackson was mentally fit and intelligent. Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King, Jr., was among those to express “concern” about fairness and justice in the trial of Jamil Abdullah al-Amin. ↑

Campbell allegedly spit on al-Amin during his arrest. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.