Classified UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) documents released by hacktivist collective Anonymous raise serious questions about London’s cloak-and-dagger activities in Lebanon, and whether they may have led to the ouster of the country’s government.

Due to Lebanon’s position at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and Arabia, and borders with Israel and Syria, it has long been of enormous geopolitical significance to Western powers.

Given the decade-long Syrian crisis—which has precipitated the flow of almost two million refugees to Beirut—in which both Hezbollah, the country’s most powerful political force, and the UK government, have been so intimately involved, it is perhaps unsurprising that Lebanon is of intense interest to Whitehall.

Nonetheless, the disquieting dimensions of London’s covert operations in the country have remained largely secret. The leaked files now lay bare the FCDO’s extensive efforts to meddle in Lebanese society.

The foundation for many of these endeavors was a confidential “Target Audience Analysis’ (TAA), produced for the FCDO in March 2019 by shadowy “conflict transformation and stabilization consultancy” ARK, which surveyed perspectives and perceptions of Lebanese citizens. The document identifies “potential entry-points for strategic communications” in Lebanon; when one reads between the lines, it gives every appearance of being a blueprint for the government’s overthrow.

ARK, which has reaped untold millions from British taxpayers for running destabilizing psyops in numerous countries of interest to the FCDO, was founded by veteran Whitehall operative Alistair Harris. While an online CV presents him as a journeyman diplomat, his biography on ARK’s website refers to work on “ethno-sectarian conflict” overseas, including in Northern Ireland—a strong indication Harris’s actual affiliation is MI6, as the province is part of the UK, thus by definition doesn’t host a British embassy on its soil.

It is likely no coincidence—and highly significant—that within 10 days of Anonymous leaking these files in December 2020, Harris announced his sudden departure from the region for London after many years, to take up a post within the FCDO’s Civilian Stabilisation Unit.

A month later, UK Lebanese ambassador Chris Rampling was abruptly replaced by Martin Longden, previously UK Special Envoy to Syria, after less than 18 months in the post. Rampling is now FCDO National Security Director.

“Potential coalition for positive change”

The TAA’s stated objective was supporting the UK government’s “projects and programmes” in Lebanon, the research reportedly presenting “a sociological and psychological mapping of attitudinal and behavioural forces shaping the trajectory of a conflict, a snapshot of a complex dynamic situation,” which sought to “identify strategies for building a potential coalition for positive social change,” and “the ‘influenceability’ of specific groups that either pose a threat to, or may contribute to, positive social change.”

“Positive social change may be defined, attitudinally, as the commitment to a secure, prosperous, and inclusive future Lebanon, and behaviourally, as the willingness to take political action to achieve this vision,” the TAA stated.

The contractor was ultimately hunting for a particular segment of the population, a “Potential Target Audience” (PTA), which “saw the greatest potential for reform, or to affect positive social change through their own actions.” This constituency, “if exposed to effective strategic communications,” could be “influenced” to engage in “political behaviours leading to positive social change,” and “refrain from engaging in behaviors” limiting the potential for such upheaval.

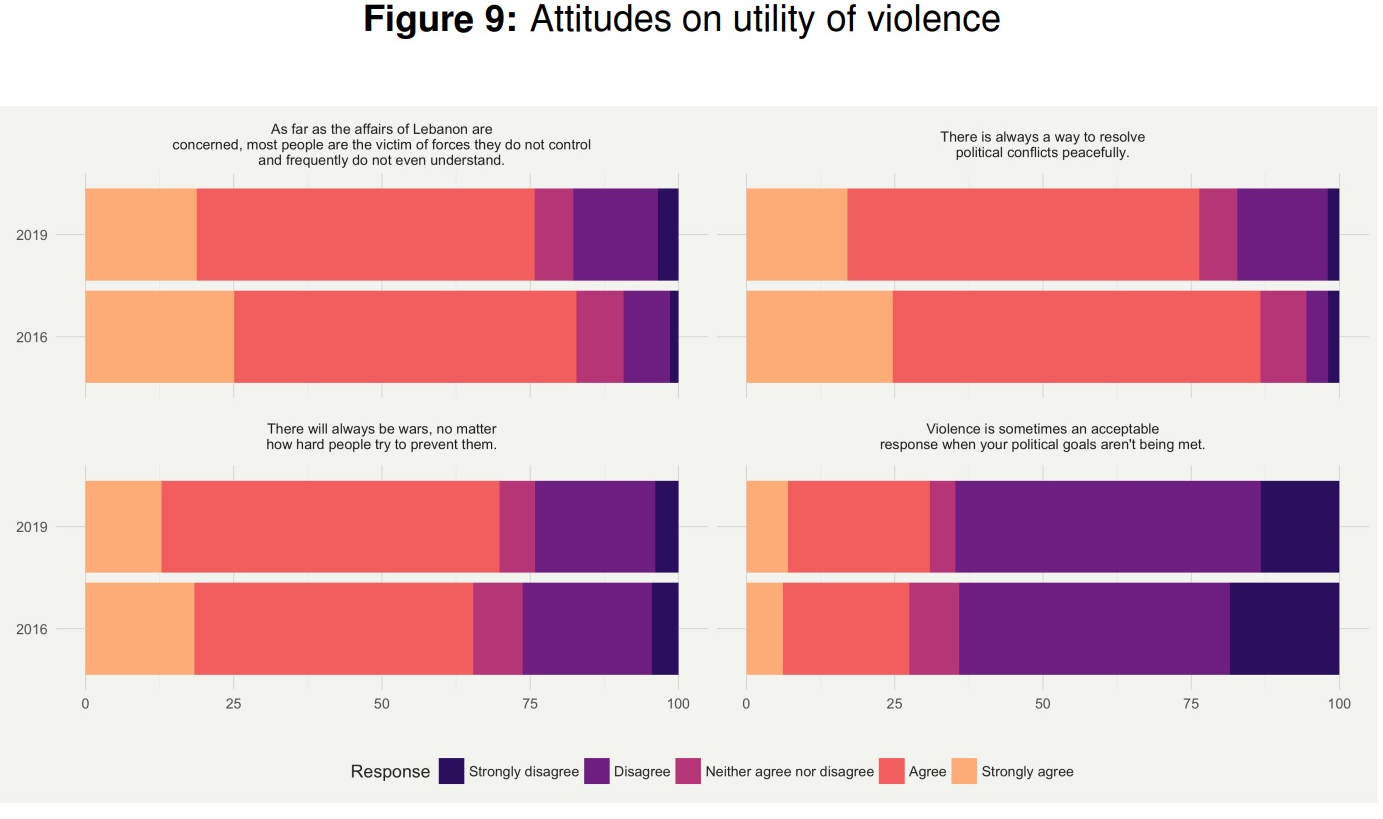

As such, ARK was particularly interested in the extent to which respondents agreed with four statements “about the use and efficacy of violence,” including whether they concurred with the notion that “violence is sometimes acceptable when your political goals aren’t being met.”

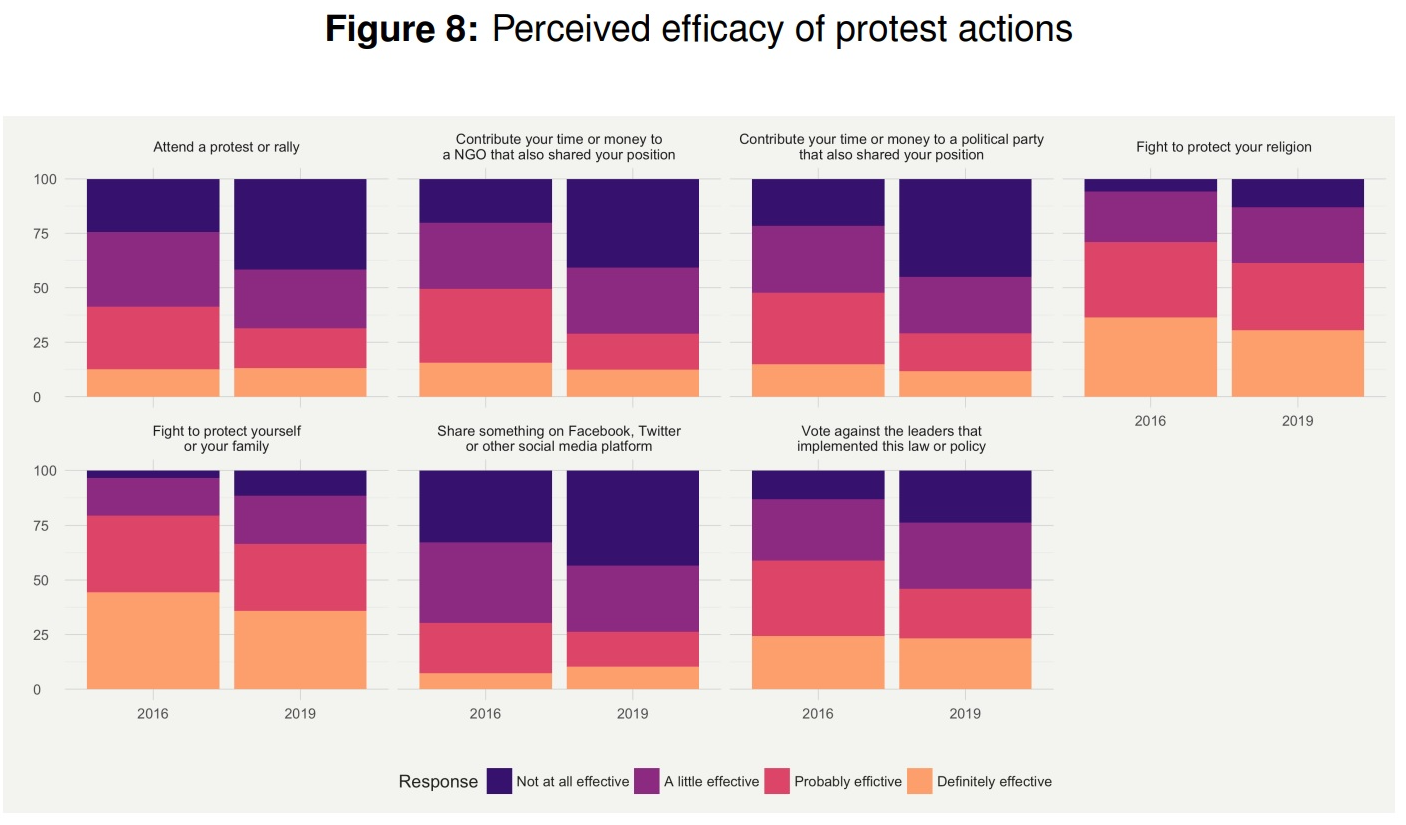

The contractor also sought to gauge the “likelihood and perceived efficacy” of a septet of political actions among respondents—attending a protest or rally; contributing time or money to an NGO; donating to a political party; fighting to protect oneself or one’s family; sharing “something” on social media; voting against leaders “that implemented this law or policy”; and “[taking] up arms to protect one’s religion.”

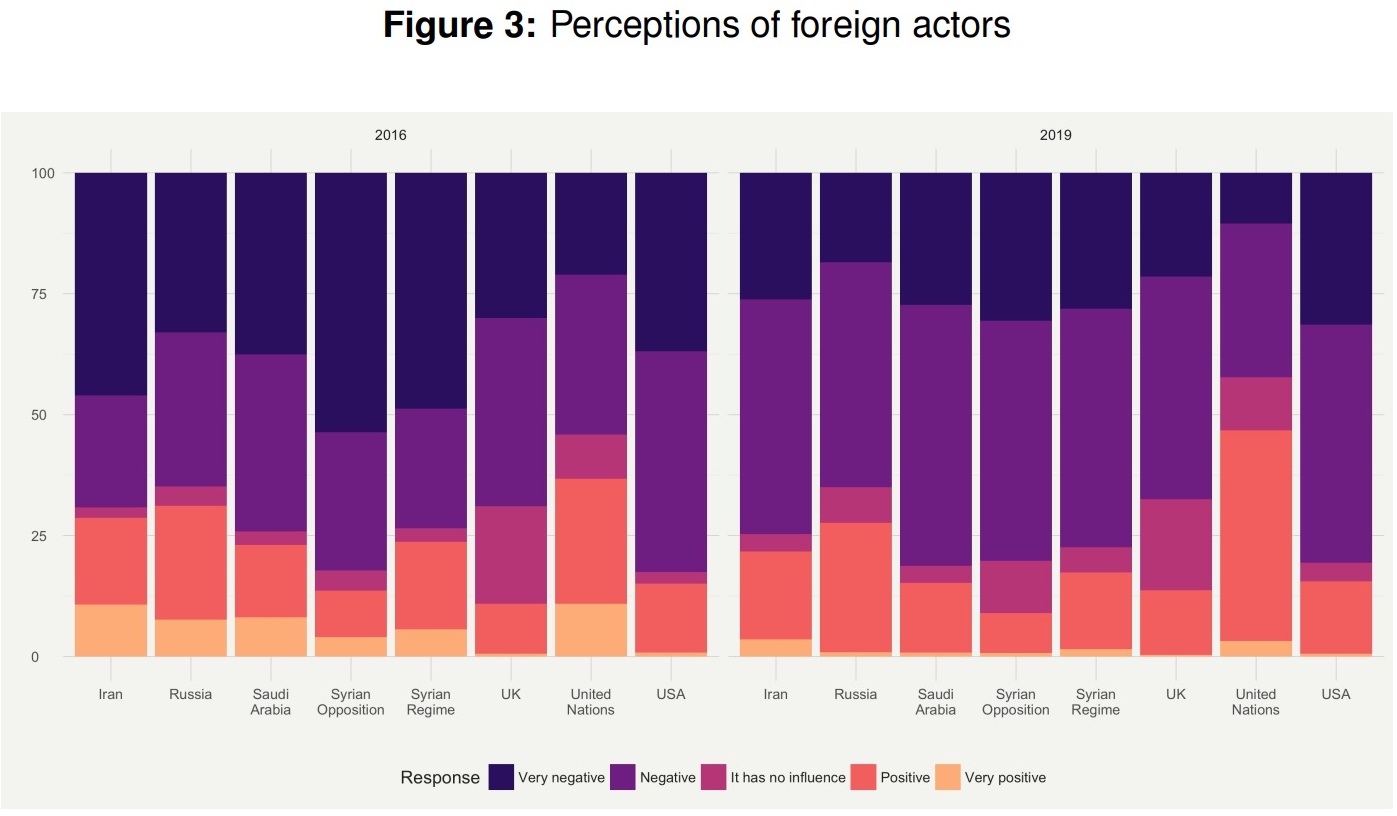

ARK acknowledged there were “real obstacles to meaningful social change” in Beirut, noting in a bitter irony that “the perception foreign actors may have undue influence” over government policy was “not unreasonable.” An accompanying graph, mapping local “perceptions of foreign actors,”, indicated that, out of Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the Syrian opposition, Syrian government, UK, United Nations and U.S., Whitehall was by far the least trusted among Lebanese citizens, bar the Syrian opposition.

Luckily though, the UK was also the most widely perceived to have “no influence” in Lebanon.

Nearly all respondents also had some complaint or other with Lebanon’s status quo, “most notably with respect to the state of the economy and economic expectations for the future, and to a lesser extent, concerning matters of safety and security.”

The greatest political and policy concerns were economic in nature, with unemployment, poverty and economic growth ranked the top three “most serious” problems facing the country—they “derived strongly” from perceptions of widespread corruption at the highest levels of Lebanese society.

The TAA also extensively probed the “media usage” of Lebanese citizens, and which sources of news and political information they trusted most, so they could be leveraged accordingly by Whitehall psyops efforts. An overwhelming majority of respondents said they “never [used]” the BBC, and it was among the least trusted of the platforms listed.

Nonetheless, television remained the most “used and trusted” information source for Lebanese citizens, followed by “news sites on the internet” associated with specific stations.

“The three most used and most trusted television channels were MTV, LBC and OTV, followed by Manar and Mustaqbal … Lebanese tended to have a higher degree of trust in one or two specific channels but also regularly consumed news from other channels,” the TAA reported.

“Important speeches were also likely to drive individuals to specific channels at times. Of the channels individuals were most likely to watch even if they distrusted, Christians were most likely to watch Hezbollah-affiliated Manar and Future Movement-affiliated Future TV. Shiites were most likely to watch MTV and LBC, even if they distrusted these channels.”

Overall, friends and family were “by far” regarded as “the most trustworthy sources of information,” and the significance of social media and encrypted messaging app WhatsApp were emphasized, as they “provided many with an important conduit to information shared by family and friends.”

“Participate in the change process”

In the end, ARK identified a suitable PTA, amounting to 12 percent of the Lebanese population. What set this group apart from the general public was they “saw a greater potential for reform, or to affect positive social change through their own actions,” demonstrated “willingness and capacity to participate in this change process,” and were “amongst the most likely to engage in positive forms of civic action, if given the opportunity to do so.”

“[The] PTA were more than twice as likely, relative to the general public, to reject statements such as, ‘violence is sometimes acceptable when your political goals are not being met,’” the TAA stated. “However, the rejection of violence within this group did not necessarily mean the rejection of other forms of contentious politics [emphasis added]. Members of this segment were also significantly more likely to state they would participate in protests, and more likely to believe that protest or similar actions could effectively lead to change.”

The only questions remaining for ARK were, “what might be done to enable other Lebanese to have similar confidence in their potential to contribute to positive social change?” and “how might this segment of the population … be grown to include a larger fraction of the public?”

Due to widespread consensus that social or political change was “difficult or even impossible to achieve,” strategic communications were to propound the idea that “ordinary citizens” can indeed achieve change, by unifying against the Lebanese establishment.

“Specifically, social change messages should focus on real and perceived barriers to civic participation, acknowledging the real challenge these barriers may present, and enumerating or exploring how these might be overcome and how the public might be motivated to participate,” ARK continued.

Given local skepticism about the prospect of reform, “future, unmet expectations of change” had the obvious potential to exacerbate such cynicism—therefore, it was considered vital that “promoted social change goals” were “for the most part … short-term, realistic and achievable.”

“Building momentum for social change and enhancing the potential for social change—even in modest increments—will likely have more positive long-term effects. In contrast, the failure of more ambitious or far-reaching efforts has the potential to further undermine confidence in the potential for the government, political parties or other decision makers to reform or respond to citizen demands,” the TAA said.

Moreover, as a majority of Lebanese viewed foreign influence as “both pervasive and mostly negative,” “linking social change goals even falsely to foreign interests or agendas” would “remain a risk,” to be mitigated “through meaningful [emphasis in original] partnerships with both Lebanese government institutions and local civic society organisations.”

One suggested approach was highlighting “where change has been achieved, or where threats to Lebanon’s stability have been countered or avoided, despite significant challenges”—for example, Lebanon’s military and security services cracking down on “extremist groups from Syria” operating within the country—which has led to scores of refugees being arbitrarily detained on terror charges, and brutally tortured. Working with local communities, local governments and municipal authorities on “realistic, achievable and relatively short-term social and political change goals” was to be “prioritised.”

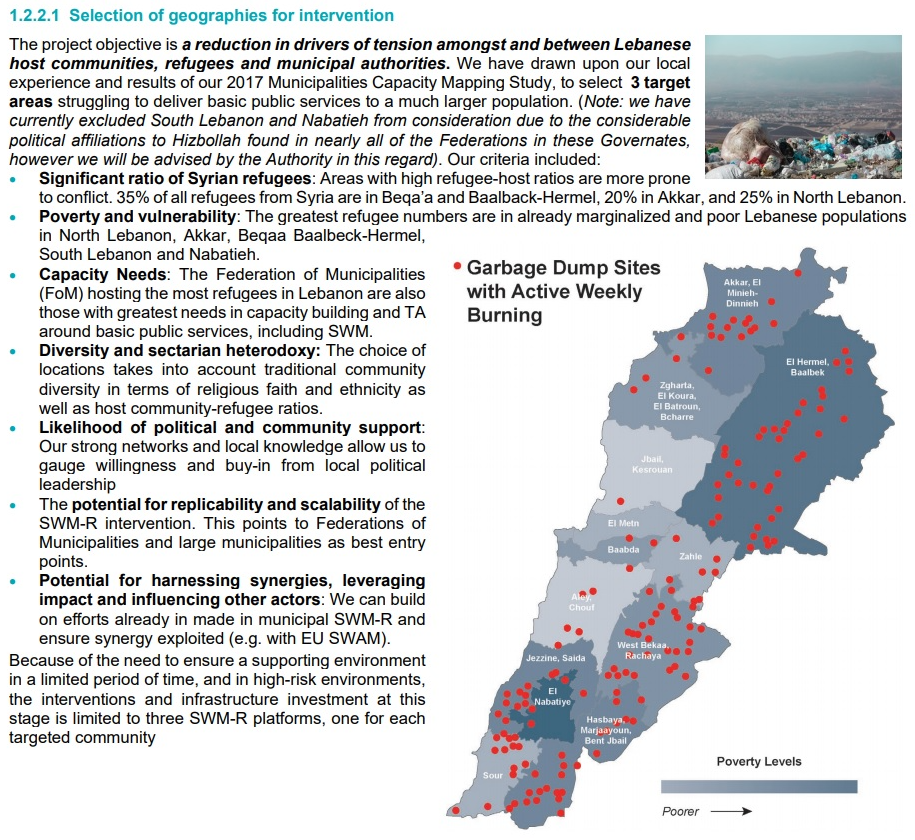

“Lebanese were more likely to have seen evidence of responsive government at local levels, where for example, some municipalities have taken more-effective measures to help manage tensions between Lebanese host-communities and Syrian refugees, or where municipalities have been able to provide solutions to public grievances, like the ‘garbage crisis,’” the TAA concluded.

Accordingly, one of the FCDO programs in Lebanon inspired by ARK’s TAA was “Peacebuilding and Rapid Stabilization through Solid Waste Management.” It ran April 2019 – March 2021, and cost Whitehall £4.7 million.

The project sought to “reduce drivers of tension amongst and between Lebanese host communities, refugees and municipal authorities”—thus presumably minimizing the scope for in-fighting among the country’s varied inhabitants, providing an example of “responsive government at local levels,” and ensuring citizens remained arrayed against Lebanon’s political elite.

Underlining the program’s information warfare objectives, in a separate submission to the FCDO, ARK proposed that the initiative’s activities be “shared and amplified” via Ana Hon (“I am here”), a social media brand it created to promote “positive local initiatives” and encourage citizens to “participate in or replicate” such activities. Its total reach was said to be 16.3 million people–three quarters of them aged 18-35 – including an estimated 37 percent of Beirut’s population. A shaky phone camera video clip of local residents cheerfully clearing away garbage was duly shared by the page in August 2019. While brief, its underlying message to viewers couldn’t be clearer – the state can’t solve simple problems, so take matters into your own hands.

Another leaked document indicates that ARK’s activities in the country are so extensive that it has a dedicated Lebanese production hub, which “generates content to support projects that [are] disseminated on a wide variety of platforms, from websites and social media channels to local television news and regional satellite channels.”

In all, it manages 30 “targeted” Facebook pages disseminating content every day—just one of its Facebook assets is said to reach 45 percent of Lebanon.

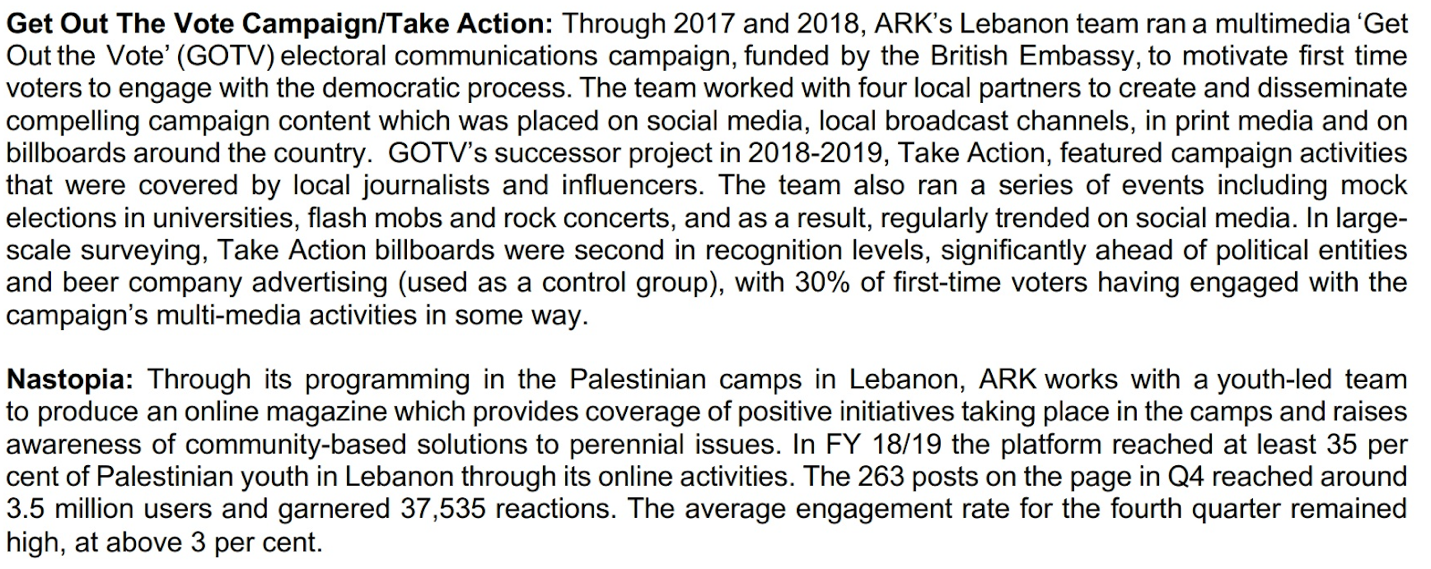

These pages were instrumental in ARK’s elaborate and covert 2017-2019 electioneering efforts, “Get Out The Vote” and “Take Action,” detailed in the file. Funded to the tune of millions by the British Embassy in Beirut, the campaigns sought to “motivate first time voters to engage with the democratic process,” creating campaign content amplified via social media, local TV channels, print media and billboards around the country.

“Campaign activities … were covered by local journalists and influencers. The team also ran a series of events including mock elections in universities, flash mobs and rock concerts, and as a result, regularly trended on social media,” ARK wrote. “In large scale surveying, Take Action billboards were second in recognition levels, significantly ahead of political entities and beer company advertising … with 30% of first-time voters having engaged with the campaign’s multi-media activities in some way.

“Identity shift”

Lebanon’s “garbage crisis,” which ARK cynically sought to exploit, is quite some public grievance—in fact, it almost led to the government’s downfall in 2015.

In July that year, Beirut’s primary landfill was shut down—officials failed to identify an alternative destination in advance, so it wasn’t long after the site’s closure that the streets became deluged with thousands upon thousands of tons of refuse.

In turn, Lebanese citizens began convening regular street protests in ever-growing numbers, leading to an estimated 20,000 people occupying the historic Riad El Solh Square on August 23rd, and engaging in violent clashes with police.

The number of demonstrators consistently swelled over subsequent days, rising to as many as 100,000 at one stage, chants and placards no longer referring to garbage, but outright revolution. The fervor grew to such an incendiary extent that Lebanese army units had to be deployed to suppress the street fighting.

![Demonstrators throw stones during a protest on August 8 as they try to break through a barrier to the parliament building following Tuesday's blast in Beirut, Lebanon [REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani [Daylife]](https://covertactionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/demonstrators-throw-stones-during-a-protest-on-aug.jpeg)

The loudest calls for the government’s resignation emanated from protest group You Stink! – a double entendre referencing the stench of both uncollected refuse and Lebanon’s political elite.

Once the protests fizzled out, You Stink! morphed into political campaign group Beirut Madinati – professors from the American University of Beirut were among its founders, including economics professor Jad Chaaban, who previously worked for the World Bank, and created the Lebanese Economic Association, which receives support from Booz Allen Hamilton, the Ford Foundation, and Washington intelligence cutout USAID.

In the end, Lebanon’s rulers were not pressured into providing proper waste management solutions, let alone unseated from power. However, as academic Adham Saouli observed, the protests were highly impactful. A highly religiously divided society, Lebanon’s political system splits power between both Sunni and Shia Muslims, and Christians, its electoral structures reinforcing sectarianism at the highest levels, which thoroughly permeates downwards.

“The August protest … constituted a wake-up call, a cognitive and identity shift that led many to realise their common socioeconomic grievances and identify a new rival: the political class. Popular uprisings bring agency back to people. In Lebanon a sense of powerlessness towards politics and politicians had generally permeated the social consciousness of many; the demonstrations brought back power and hope,” Saouli wrote at the time.

Of course, it is precisely this disconnect between Lebanese politicians and citizens that ARK sought to identify, and Whitehall seeks to leverage to its advantage. Six months after “‘Peacebuilding and Rapid Stabilisation through Solid Waste Management’” was launched, large-scale public disturbances again engulfed Beirut. The “garbage crisis” protests of four years prior were widely invoked in mainstream media coverage, as a prelude to the current strife. As the New York Times explained to its readers, “to make sense of Lebanon’s protests, follow the garbage.”

“The Lebanese have finally had enough of a system that has enriched the political elite while failing to build a stable economy or provide basics like reliable running water or consistent waste management,” the paper stated. “They are demanding an end to corruption and mismanagement, as well as the crony sectarianism that enables it.”

The demonstrations were far larger and even bloodier this time, becoming significantly enflamed when the military began employing beatings, tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition against peaceful protesters. In a perverse coincidence, some of this arsenal may have been supplied by Whitehall—analysis produced by Action on Armed Violence reveals that in 2015, Beirut spent £2.3 million on UK-made weaponry, in breach of international embargoes.

“This is getting tired”

The protests were watched closely by ARK, with aforementioned founder -and- chief Alistair Harris publishing a series of blogs on LinkedIn about developments on-the-ground. His first, on October 19—two days after the unrest erupted—noted, undoubtedly with some pride, that “Lebanese have been increasingly more likely to attribute social, economic and other problems to a ‘corrupt elite’ rather than to ‘other’ Lebanese groups or confessions.”

The next day, he wrote that data ARK had collated on social tensions in Lebanon over the previous two years provided “several indicators” of how the country’s political elite would respond to what was unfolding. In a passage rendered rather chilling in light of the leaked files, Harris predicted that Lebanese leaders would blame “foreign actors with ‘interests’” in the country for the disorder, but this would have little traction with demonstrators, as “this is getting tired; it’s been the elite refrain for years.”

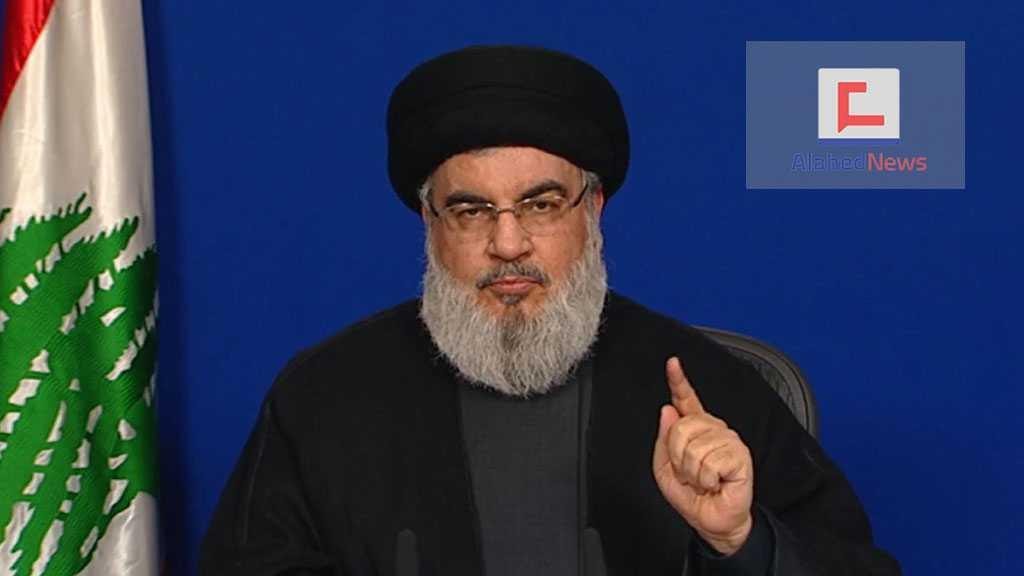

Just as forecast, on October 25 Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah gave a speech in which he made clear his party–the country’s most powerful–supported the demands of protesters, but warned that they were being “exploited by embassies” and “well-known political forces” were providing “management, coordination and funding.” He also asked citizens to consider whether these actors “care for the interests of the Lebanese people.”

Four days later, Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced not only his own resignation, but that of his entire cabinet, on the basis that he wanted to give Lebanon a “positive shock”–a move strongly opposed by Hezbollah’s leadership.

The protests, which continue to this day and served to greatly disrupt the country in every way, have posed immense challenges to the movement and left them politically isolated. London no doubt enthusiastically welcomes these difficulties, given it has in recent years designated Hezbollah’s political wing a terrorist group, and frozen its assets.

Harris was surely correct that elite talk of “foreign actors with ‘interests’” fell on deaf ears due to the “refrain” having been so frequently invoked by Lebanese leaders in recent years, although the leaked FCDO files make clear the charge is entirely true—and ARK is just one malign “political force,” in Nasrallah’s phrase, engaged in the “management, coordination and funding” of destabilizing efforts and elements in the country.

Two FCDO operations in Lebanon influenced by the company’s Target Audience Analysis are particularly significant in this regard—’Female Political Participation’ and ‘Youth Political Engagement.’ For one, women and young Lebanese were at the forefront of the October 2019 “‘revolution’,” many of whom were no doubt exposed to ARK’s assorted “strategic communications” campaigns in the months and years prior.

However, the documents make clear that London had longer-term objectives in pursuing these programs, with one referring to building “a pipeline of potential future women leaders,” in support of increased female representation in the 2022 national and municipal elections.

Evidently, under the fraudulent aegis of progress and empowerment, Whitehall seeks to identify, groom, and promote individuals who could make up Lebanon’s next political generation, and ensure that they are well-placed to take power when the country’s troublesome incumbent leaders are finally swept away for good.

If and when that does come to pass, it will no doubt further destabilize Hezbollah, thus making a total political takeover of Lebanon—a key ally of Damascus and Tehran—easy pickings.

Who says the age of imperialism is over?

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions.

Follow him on Twitter @KitKlarenberg.

[…] Leaked Foreign Office files in December 2020 reveal that seven months before the protests erupted, the UK commissioned a Target Audience Analysis in Lebanon, which sought to pinpoint a segment of the population that could effectively be mobilized to “affect positive social change,” and provide methods of reducing tensions between sectarian communities to unify them in opposition to the country’s ruling elite. […]

[…] Pour le lectorat anglophone, cf ce lien : https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/05/27/secret-documents-expose-british-cloak-and-dagger-activit… […]

[…] «Secret Documents Expose British Cloak and Dagger Activities in Lebanon», Kit Klarenberg, Covert Action Magazine, 2021. «Britain’s Secret Propaganda War in Lebanon», Kit Klarenberg, The Cradle, 2021. «Leaked files expose Britain’s covert infiltration of Palestinian refugee camps», Kit Klarenberg, The Cradle, 13 de agosto de 2022. […]

[…] Secret Documents Expose British Cloak and Dagger Activities in Lebanon Kit Klarenberg, Covert Action Magazine, 2021. […]

[…] « Secret Documents Expose British Cloak and Dagger Activities in Lebanon », Kit Klarenberg, Covert Action Magazine, 2021. – « Britain’s Secret Propaganda War in […]

[…] unify them in opposition to the country’s ruling elite. Reading between the lines, it gives every appearance of a blueprint for the overthrow of the Lebanese […]

[…] Pour le lectorat anglophone, cf ce lien : https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/05/27/secret-documents-expose-british-cloak-and-dagger-activit… […]

[…] Pour le lectorat anglophone, cf ce lien : https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/05/27/secret-documents-expose-british-cloak-and-dagger-activit… […]

[…] https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/05/27/secret-documents-expose-british-cloak-and-dagger-activit… […]

Mi6, CIA, MOSSAD etc are different names for the same glodal terror network. In this case as with the Syrian situation & the ongoing Palestinian genocide is probably in order to further the “greater israel” plot.

If the new UK Ambassador to Lebanon was the UK Special Envoy to Syria, you can bet that MI-6 will be no less intimately involved in its destabilization efforts than it was.