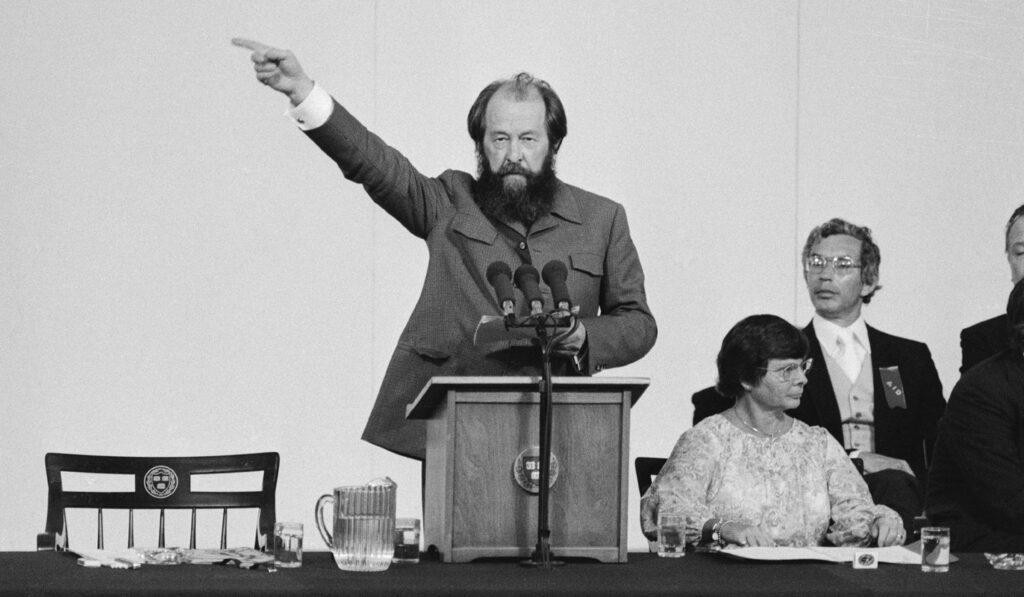

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is perhaps the most well-known Soviet dissident. He was the author of The Gulag Archipelago, a three-volume work originally published in 1973 which significantly turned international public opinion against the Soviet Union.

Described by Canadian psychologist and right-wing media personality Jordan Peterson as the most important book of the 20th century, the text and its author have seen a resurgence of popularity today. Quotes from Solzhenitsyn proliferate on social media, a more popular example being his injunction to “live not by lies.”

But Solzhenitsyn did not seem to abide by his own pronouncement during his life.

Throughout his literary career, he crafted a dystopian image of the USSR, unmoored from a broader historical analysis of the global situation, which persists to this day.

In the Western press Solzhenitsyn was made out to be a courageous dissident speaking out against tyranny.

However, history shows that he was mendacious, opportunistic, and a fascist sympathizer. The dissident and his work were used as anti-communist propaganda during the Cold War and the purported revelations of The Gulag Archipelago left an ugly stain on the legacy of the USSR.

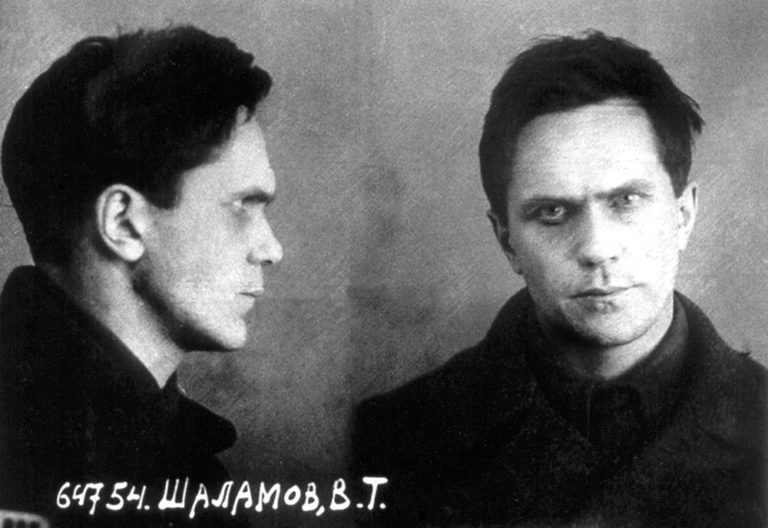

While one can acknowledge that Solzhenitsyn suffered greatly from his prison experiences, this does not explain or excuse how he allowed himself to be used by the U.S. empire. For example, there were other Soviet dissidents, such as Varlam Shalamov, a writer who also spent a large portion of his life in the labor camps, who never publicly denounced the Soviet Union as a whole or allowed his literary works to be weaponized by the West. Thus, spending time in the Gulag was not necessarily a prerequisite for capitulating to Western imperialism.

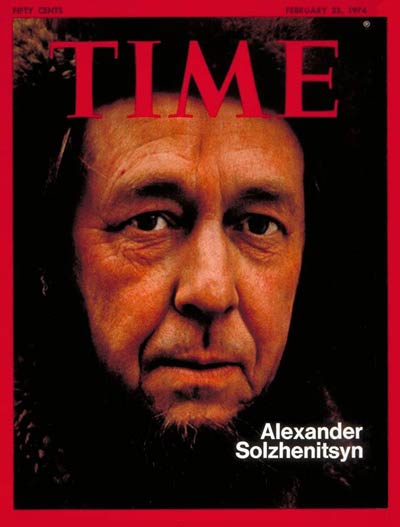

Unlike Shalamov, Solzhenitsyn received a warm welcome in Western Europe and the United States. He was awarded a Nobel Prize, gave lectures at Harvard University, and even graced the cover of Time magazine.

When the Royal Swedish Academy decided to present Solzhenitsyn with the Nobel Prize in Literature, the CIA, in a declassified document, noted how that decision would pose a problem for the Soviet leadership. However, during the Khrushchev era, Solzhenitsyn did not have problems getting his fictional work published in the Soviet Union.

After Nikita Khrushchev’s notorious “Secret Speech” in 1956, condemnation of the Stalin era was en vogue even within the Soviet Union itself. Under Leonid Brezhnev, the ubiquitous anti-Stalin attitude shifted, and Solzhenitsyn began to face publishing difficulties. In 1963, The Literary Gazette carried cautious criticism of Solzhenitsyn for the bleak picture he painted of the Stalin period.

A little later, the CIA, by its own admission, eagerly awaited his upcoming novel August 1914, stating that it “may be the most thought-provoking and controversial critique of the Soviet system’s fundamental principles that he has yet written.”

Shalamov, however, who had none of his prose published in the Soviet Union until after his death, never embarked on sweeping critiques or condemnations of the Soviet political project even though he denounced “Stalinism.” Solzhenitsyn’s political stance and the way in which he cooperated with Western imperialism had more to do with his personal history and character than his prison experiences, which Shalamov shared.

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was born on December 11, 1918, a little more than a year after the October Revolution. His father was an officer in the Imperial Russian Army and was killed in a hunting accident before Aleksandr was born.

Solzhenitsyn’s mother was the daughter of a wealthy Ukrainian landowner, but after the revolution and the ensuing redistribution of wealth, she raised him with modest means. When he was young, his mother taught him the Russian Orthodox faith in secret but, as Solzhenitsyn grew older, he became an atheist.

Solzhenitsyn attended university in Rostov where he studied physics and mathematics; he also enrolled in history, literature and philosophy courses by correspondence. During the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet dissident-to-be served in the Red Army. He attained the rank of captain and commanded an artillery fire correction detachment.

In The Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn claimed that he served at the front. Yet it is difficult to find any evidence for this, and even if he was technically at the front line, as a captain he most likely would have directed troops offsite from the battlefield. Toward the end of the war, he sent a letter to his friend Nikolai Vitkevich, voicing criticisms of Stalin as well as referring to him as “the Mustachioed One.” The letter was intercepted and resulted in Solzhenitsyn’s almost immediate arrest.

This alleged incident is highly suspicious. A thrice-decorated military captain such as Solzhenitsyn would certainly have been aware that the authorities monitored correspondence, as well as how tense the internal situation was during World War Two.

Two friends from his youth, Kirill Simonyan and Lidia Yezherets, noted how that sort of risk-taking behavior did not match what they called his cautious and cowardly character, nor did the letter accurately reflect his political views at that time. It has been speculated, by Simoyan and others, that Solzhenitsyn purposefully wrote a subversive letter as the fighting became more desperate so that he would be sent away from the dangerous front lines.

If this truly was his intent, he succeeded. The Soviet dissident was imprisoned for six months, during which time the war ended. He even recalled seeing celebratory victory fireworks through his prison-cell window.

At the end of his six-month prison stay, Solzhenitsyn claimed he was sentenced to eight years of hard labor in the camps. Yet eight-year terms were practically unheard of at that time. Terms of Soviet imprisonment were usually by fives: 5, 10, 15, 25, etc. At one point in The Gulag Archipelago, he admits to being given a ten-year sentence. How is it that his length of imprisonment was reduced by two years?

One possibility is that Solzhenitsyn acted as an informant. In her book about her life with him, Sanya: My Life With Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, his ex-wife Natalya Alekseyevna Reshetovskaya alleged that his punishment was mild because, while under interrogation, he had confessed that she and his friend Nikolai Vitkevich as well as another confidant and a man he had met on the train were “anti-Soviets conspiring to change the state.”

There is evidence to support Reshetovskaya’s claims. Vitkevich, the friend with whom Solzhenitsyn had exchanged letters during the war, was arrested at approximately the same time as he and served a ten-year sentence. When he saw the interrogation documents claiming his and his friend’s guilt, Vitkevich felt betrayed and disavowed the existence of the anti-Soviet organization to which he had been accused of belonging. Solzhenitsyn denied the whole incident.

One of the camps Solzhenitsyn did time in was a construction camp in Moscow. About one year into his term he lied to the authorities, claiming to be a nuclear physicist which got him transferred to a scientific research facility staffed by prison inmates.

In 1950, Solzhenitsyn was sent to a camp for political prisoners in Soviet Kazakhstan. Toward the end of his prison term, he developed a malignant tumor. The cancerous growth was operated on successfully in 1954, one year after his release. Solzhenitsyn had been released in 1953 with the sentence of “exile for life” but, after Stalin’s death, he was exonerated. Had he remained exiled, history would have taken a very different path.

The Gulag Archipelago is arguably Solzhenitsyn’s most famous work and was heavily promoted in the West. The book, still widely discussed today, was translated into 35 languages and sold more than 30 million copies worldwide. At the beginning of the 21st century, it was required reading in post-Soviet Russian schools.

While Solzhenitsyn was still drafting his three-volume series, he extended an invitation to Varlam Shalamov, asking him if he would like to collaborate on the work. Shalamov refused because he had disagreements with Solzhenitsyn’s views as well as a belief that long novel-like structures distort the truth. (He once wrote a book called Vishera: An Anti-Novel.)

One of their disagreements was over the role of the medical center within the camps: Solzhenitsyn adamantly insisted that the camp doctors deliberately made patients sicker and that the entire medical sector was there only for nefarious purposes; Shalamov, who had worked as a paramedic in the camps as well as having his life saved by camp doctors, strongly disagreed.

While there may have been individual doctors who abused their positions, the main reason camp medical care was insufficient was the lack of proper supplies due to theft and supply-chain difficulties.

The Gulag Archipelago contains no citations and very little evidence to support Solzhenitsyn’s more extreme claims. Documentation of arrests and deaths are lacking, vague and inconsistent. The stories, rumors and anecdotes presented as facts were sourced largely from the author’s fellow prisoners; from where he derived his statistics regarding deaths and arrests is unclear.

Although The Gulag Archipelago was taken by the West as a concrete and scientific historical document, it was, as the subtitle of the trilogy suggests, an “experiment in literary investigation.” The Soviet dissident was by and large a fiction writer, not a historian or statistician.

After the fall of the USSR, with the opening of state archives, The Gulag Archipelago was revealed to be full of fabrications and gross exaggerations. In fact, Solzhenitsyn’s number of deaths are irreconcilable to the population growth that occurred in the Soviet Union at that time.

Historian Vadim Z. Rogovin wrote, “Solzhenitsyn’s work, much like the more objective works of R. Medvedev, belong to the genre which the West calls ‘oral history,’ i.e., research which is based almost exclusively on eyewitness accounts of participants in the events being described. Moreover, using the circumstance that the memoirs from prisoners in Stalin’s camps which had been given to him to read had never been published, Solzhenitsyn took plenty of license in outlining their contents and interpreting them.”

Natalya Reshetovskaya, Solzhenitsyn’s first wife, observed that he himself did not view his book as “historical research, or scientific research, but it was rather a ‘camp folklore’ collection.”

This account matches his original intention for the book, which was that it would be written by many Gulag veterans to form a “choir of different voices.”

Even Nikita Khrushchev’s son, Sergei, compared The Gulag Archipelago to fiction: “I think that [it] was even bigger than ‘Doctor Zhivago,’ as an example of, from the American point of view, successful propaganda.”

One might say it was very successful. Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago was actively weaponized by the CIA to reinforce anti-Communist propaganda about the lack of “freedom of expression” within the Soviet Union. Through their various book publishers, the CIA worked diligently to make sure that Doctor Zhivago made its way into the hands of Soviet citizens.

Although there is no publicly documented link between Solzhenitsyn and the CIA, it is likely that they used a similar strategy with The Gulag Archipelago.

After his camp experiences, Solzhenitsyn converted back to the Russian Orthodox Church of his childhood. The older he grew, the more pious he became. Yet Solzhenitsyn did not hesitate to contrast the West to the East and he vociferously proclaimed the former’s inherent superiority.

While he had criticized the West for its materialism and lack of religious faith, in an interview Solzhenitsyn stated that “I am not a critic of the West. I am a critic of the weakness of the West.” By “weakness” he meant the West’s lack of military intervention into other budding socialist countries.

Notably, Solzhenitsyn supported the Vietnam War, and he accused the anti-war movement of causing the deaths that occurred in Southeast Asia after the U.S. military’s withdrawal. However, after the fall of the USSR, he became increasingly anti-Western and was a strong supporter of Vladimir Putin.

The Soviet dissident saw the West, as well as NATO’s eastward expansion, as a destructive force attempting to destroy Russia’s culture and traditional way of life. Like controversial Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin, he saw Soviet socialism as equally anti-Slavic because of Marxism’s origins in Western Europe. Solzhenitsyn became critical of the Westernization that occurred in Russia under Boris Yeltsin and adopted a political position of pan-Slavic nationalism.

As a result, toward the end of Solzhenitsyn’s life, the Anglophone press turned its back on the former poster boy of anti-communism. He was criticized for his religious attitude as well as his chauvinistic views, yet the only thing that had changed in his politics was his orientation away from the West.

As we still see today, the media of the imperial core do not tolerate anti-Western sentiments or any authentic form of nationalism, even when espoused by figures who were formerly useful to the CIA and the national security state.

In the third volume of The Gulag Archipelago, which was written years after the initial volumes and with a different tone, Solzhenitsyn lamented that Hitler did not succeed in invading Russia far enough to “liberate” the Gulag inmates. He wrote that many prisoners he knew wished for this as well, even though Hitler viewed Slavic peoples as an inferior race deserving nothing but enslavement. The Russian author’s remarks about the Führer, his recurring mentions of how life was easier in the Nazi concentration camps than in the Gulag, and his controversial book Two Hundred Years Together (a history of Jews in Russia) has led to his popularity with neo-Nazis.

To conflate and even negatively compare the Soviet Union’s prison labor camps to the Nazi’s extermination camps is an ahistorical analysis and an ignorant generalization. The Nazi death camps housed and killed children, practiced all kinds of horrific medical experiments on the prisoners, and certainly no one was able to earn a reduction on their sentences as Gulag inmates could.

While there were innocent people in the Gulag, there were also saboteurs and foreign spies, not to mention many recidivist and dangerous criminals such as mobsters, murderers, pedophiles and rapists. In fact, Shalamov wrote consistently about the criminals in the camps, who terrorized the political prisoners. Children were never interned there, and medical torture and experimentation on prisoners was never an approved practice as it was in the Nazi extermination camps.

Many of the abuses in the Gulag were due to corrupt local officials and were not, as in fascist Germany, government-approved practices. Solzhenitsyn’s comparison is an obfuscation of history, one which greatly minimizes the level of calculated scientific experimentation conducted by the Nazis.

As Thomas Mann said, “To place Russian communism and Nazi-fascism on the same moral level, in the measure that both are totalitarian, is superficial at best; fascism at worst. Anyone who insists on this comparison could very well be considered a democrat, but deep in their heart a fascist is already there, and naturally they will only fight fascism in a superficial and hypocritical way, while they save all their hatred for communism.”

Yet the anti-communist dissident went even further. In The Gulag Archipelago Hitler and the Nazis are portrayed favorably in comparison to the Soviet Union and communism in general.

Mann’s quote is further validated by Solzhenitsyn’s praise of fascist Spain, which he admired because it was keeping left-wing forces at bay. He even went so far as to remark how it was dangerous for Spain to democratize too fast because it could give power to the communists.

From this we can see that the Russian author was not some liberal humanist, as much as the West would have liked to present him in that way.

Regarding Shalamov, Solzhenitsyn seemed to harbor resentment about the former’s unwillingness to collaborate on The Gulag Archipelago. Upon his return to Russia, Solzhenitsyn published memoirs about Shalamov which shredded him from multiple angles.

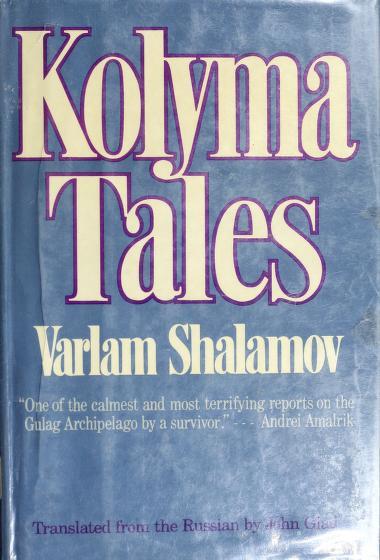

He criticized Shalamov as insufficiently patriotic and for not condemning the Soviet Union as a whole. He declared that Kolyma Tales, Shalamov’s collection of stories, was artistically unsatisfying and made ad hominem attacks on his appearance. It should be noted that Solzhenitsyn published these memoirs after Shalamov’s death.

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov was born on June 18, 1907. His parents were both teachers, but his father was also a Russian Orthodox priest who had spent 12 years doing missionary work in Alaska, a one-time Tsarist colony. Although religious, Shalamov’s father held progressive views and was sympathetic to the October Revolution. At the age of 13, Shalamov became an atheist and remained unconverted for the rest of his life.

After graduating from school, he worked at a leather factory for two years, after which he was accepted into the Soviet Law Department at Moscow State University. On the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, Shalamov took part in a Trotskyist demonstration that displayed slogans such as “Down with Stalin!” and “Carry out Lenin’s testament!” Less than two years later, in 1929, Shalamov was arrested during a raid of an underground print shop.

Sentenced to work at a chemical construction plant, he wrote an appeal to the authorities while interned there. In his letter to the head of the secret police, he called for a merciless purge of the “Thermidorian elements” of the party, which is in reference to the French Revolution. (The Thermidorian Reaction constituted the ousting of Robespierre and a turn away from Jacobinism). Trotsky wrote in The Revolution Betrayed as to how Stalin’s consolidation of power constituted a “Soviet Thermidor.” Thus, it is a Trotskyist argument par excellence.

However, Shalamov also mentioned how unpleasant it was, as a law-abiding citizen loyal to Soviet power, to be imprisoned with real criminals such as the notoriously brutal Russian gangsters. He was eventually released in 1931 but was arrested again in 1937 and sentenced to five years’ hard labor for counter-revolutionary activities. Sent to the Far North, he worked in the coal mines and gold mines under harsh conditions.

In 1943, Shalamov was sentenced to ten additional years. Back and forth between subarctic camps and the camp hospitals, eventually a doctor at the infirmary helped Shalamov attend a prisoner training course for paramedics. His conviction for Trotskyism made him ineligible for the program, but a friend erased it from his records at her own risk.

Shalamov worked as a medical assistant for the remainder of his sentence which allowed him to be released early, but he did not manage to return to Moscow until 1956. A year later, some of his poetry was published. His prose, however, remained censored in the Soviet Union.

A copy of Kolyma Tales was smuggled via samizdat to an anti-communist publishing house, Posev, which had connections to the Tsarist White Russians. Samizdat (essentially “underground literature”) were texts subjected to government censorship that circulated through unofficial channels, at times even unbeknownst to the respective authors.

Posev published Shalamov’s stories without his consent. An emigré magazine, Novy Zhurnal, also got ahold of Kolyma Tales, publishing them one and two at a time to make it appear as if Shalamov was a regular contributor to the publication. This upset the author because he did not want his writings used as a political weapon and especially did not want his stories published by the odious Posev.

Shalamov’s refusal to be affiliated with anti-communist publications garnered him criticism from some Western intellectuals as well as Solzhenitsyn, who accused him of “capitulating to the authorities.” Although Shalamov was critical of “Stalinism,” he was supportive of the Soviet project. For example, he insisted on only wearing Soviet-made shoes. He never adopted a pro-Western perspective and always upheld the positive achievements of the October Revolution, mass literacy being particularly important to him.

In 1972, Shalamov sent a letter to the newspaper Literaturnaya Gazeta stating that he was an honest Soviet citizen and disavowed Western publication of his works. Shalamov’s close female friend of the time was very upset with him about the letter, but he wished to get his poetry book “Moscow Clouds” published in the USSR and was for good reason very displeased with the Western profiteering from his works. The letter caused quite a stir within Soviet dissident circles, and many in the liberal movement disavowed him. Solzhenitsyn considered the letter to be a betrayal, declaring it as Shalamov’s “death.”

Shortly after his return to Moscow, Shalamov joined the circle of now well-known Russian dissidents such as Nadezhda Mandelstam. Yet, as time went on, he became cynical and alienated himself from the group. Shalamov grew to see samizdat as a political weapon in the struggle between the KGB and the CIA.

He became distrustful of the mad fervor of the dissident movement and, quite accurately, suspected them of political opportunism. At one point Shalamov said of the dissident movement, “They need me dead. They would push me into a hole in the ground and then write petitions to the UN.”

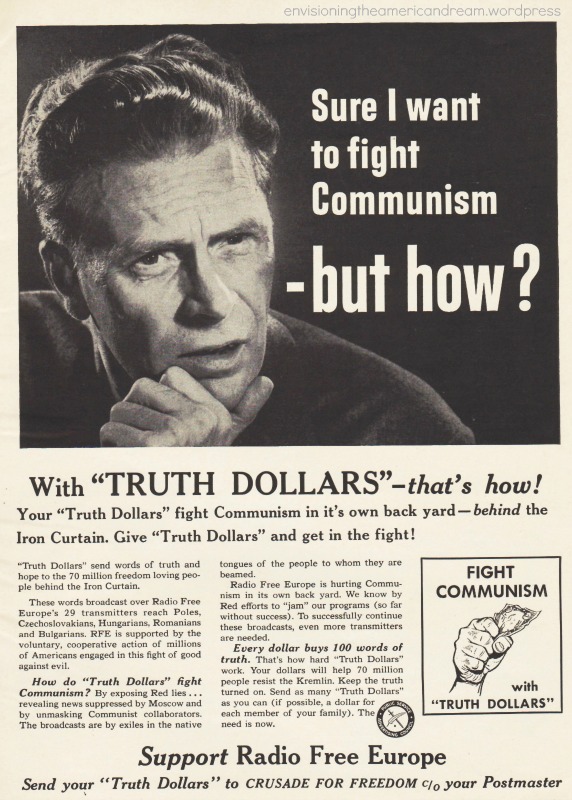

Solzhenitsyn, however, was either ignorant of the CIA’s monitoring of the dissident movement or did not care. In an interview, he praised Radio Liberty, saying, “If we learned anything about events in our own country, it’s from there.”

The CIA was the main backer of Radio Liberty and its 1969 budget for the Radio Liberty Committee (RLC) was more than $13 million. The U.S. government inundated the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries with non-stop radio programs, which aired pro-Western propaganda.

Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty were the two most prominent broadcasts with many Soviet citizens tuning in. The Soviet government desperately tried to stop these subversive radio programs, pouring a lot of money into radio jamming, but to no avail.

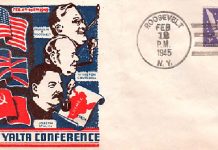

The U.S. targeted the USSR with more than just radio waves. In a National Security Council document from December 9, 1969, it was admitted that the CIA sponsored a covert action program against the USSR which supported media and “contact” activities which pushed for liberalization within the Soviet Union.

The CIA had a book publishing and distribution program through the “American Committee for the Liberation from Bolshevism” (AMCOMLIB), which was designed to provide Soviet citizens with “dissident literature.” The non-radio programs of Free Europe, Inc., and Radio Liberty Committee, Inc., also sponsored book distribution across the Soviet Union. There was even a program to distribute anti-Soviet propaganda literature throughout the Third World.

Free Europe, Inc., administered a program for exiles who fled Eastern Europe post-World War Two, even though many of these exiles would have been Nazi collaborators. FE, Inc., and RLC, Inc., distributed a total of two and a half million books across the USSR and Eastern Europe between the late 1950s and the late 1960s alone.

The book-dissemination program was successful in influencing the intelligentsia’s nascent liberal views. A 1970 U.S. document prepared by the CIA, entitled “Tensions in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe: Challenge and Opportunity,” noted how the workers and peasants were for the most part apathetic to the dissident movement, if not outright hostile. The intelligentsia, the most liberal demographic in the USSR, became the perfect political weapon of the West.

The U.S. government also recognized the important role of anti-Soviet emigrés in breeding dissatisfaction within the Soviet Union, something which became much easier after Stalin’s death. To quote from a declassified government document: “In short, the United States government concluded that anti-Soviet emigrés had a special contribution to make to United States information programs, both overt and covert, which collectively aimed at influencing the attitudes of the Soviet people and their leaders in directions which would make the Soviet government a more constructive and responsible member of the world community.”

The United States, the irresponsible hegemon that it is, highlighted the need for the Soviet Union to be more “constructive.” Even a cursory examination of the history of the country which claims to be the worldwide bastion of democracy shows the hypocrisy inherent in the U.S.’s scolding of the USSR. The United States was founded on the genocide of the Indigenous population and has a bloody history of 246 years of slavery. Eight U.S. presidents owned slaves during their times in office.

The U.S. implemented forced sterilization laws long before fascist Germany, and segregation, lynching and terror against African Americans lasted far into the 20th century. (Both the eugenical policies and the regime of white supremacy served as inspiration for the Nazis.) Not to mention the manifold imperialist wars the U.S. empire has conducted abroad, as well as its support for armed fascist groups, death squads, and military dictators around the globe.

The incubation of terrorists, harsh sanctions against countries resisting Western imperialism, the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the use of Agent Orange and napalm in Vietnam. The list of U.S. atrocities goes on and on.

Even Solzhenitsyn’s grossly exaggerated figures about the Gulag pale in comparison to the global horror and destruction that makes up the history of imperialistic capitalism. While there were excesses perpetrated by the Soviet internal security services, they nowhere near compare to the Nazis’ indiscriminate slaughter of “inferior” peoples, the treatment imperial Japan meted out to the Chinese, and the general immiseration and brutality suffered by the working class across the globe.

The Soviet Union succeeded in raising the standard of living for millions of people, eliminating homelessness, achieving mass literacy, extending life expectancy, as well as equality for women. The same certainly cannot be said for the United States.

The national security state’s weaponization of dissidents, literature and media persists to this day. The dismantling of USAID exposed the omnipresence of U.S. propaganda activities, but these endeavors continue. The State Department has resumed funding the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a front for promoting U.S. interests abroad, while programs purportedly aimed at alleviating poverty remain frozen.

As the China-hawk wing of the U.S. political establishment gains power and places war with China via Taiwan as a proxy on the agenda, Radio Free Asia (an equivalent of Radio Free Europe) and The Epoch Times, which is run by the CIA-backed Falun Gong cult, amp up their output of anti-China propaganda.

As history has demonstrated, the U.S. empire will use media, literature and art to further its goals. Dissidents are used unless they recant their pro-Western stance, after which they are discarded. As was shown after the disastrous collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing economic genocide, whatever flaws another country may have had can never compare to the havoc wreaked by imperialism.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Shaenah Batterson is a polemicist and poet located in Eugene, Oregon.

She writes a Substack called The Red Letter and cohosts the podcast Captive Minds.

Shaenah can be reached at shaenahbatterson@icloud.com.