[This article continues CAM’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War.—Editors]

April 30, 2025 marked the 50th anniversary of the end of the Indochina War, which lasted roughly from 1962 to 1975.

In the United States, a revisionism has long taken hold in which American soldiers have been imagined as victims of perfidious communist governments.[1]

For the people of Indochina, however, the damage caused by the U.S. aggression remains unyielding.

Erin Lin is a political science professor at The Ohio State University who traveled to Cambodia to interview farmers and others in an attempt to assess the legacy of U.S. bombing during the Indochina War.

In When the Bombs Stopped: The Legacy of War in Rural Cambodia (Princeton University Press, 2024), she shows that undetonated ordnance still litters the Cambodian countryside, rendering some of the country’s most fertile land unworkable, turning farmers away from commercial agricultural production, and helping to lock rural Cambodians in a cycle of poverty.

According to Lin, many rural Cambodians remain haunted by the weapons unleashed long ago by pilots who may now be dead. Parts of Cambodia are dangerous to travel because of the ordnance. Lin herself could only travel in certain areas with professional de-miners who taught her how to identify and locate bombs.

Lin writes that “our failures in military technology—the bombs’ failures to explode on impact—have drained Cambodian fields of their safety and economic potential.”[2]

The latter comments provide a damning rebuke to Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and other architects of the U.S. bombing of Cambodia, which began in the mid-1960s and continued until the triumph of the left-wing Khmer Rouge in 1975.

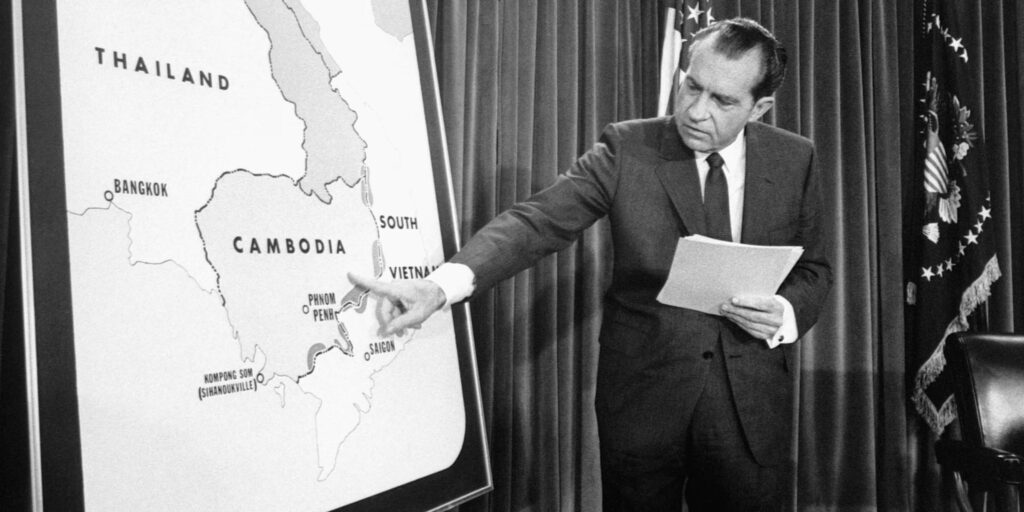

The original purpose of the U.S. bombing was to halt North Vietnamese supplies to South Vietnam along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which passed through Cambodia.

The Johnson and Nixon administrations, furthermore, aimed to undermine the regime of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, Cambodia’s chief of state from 1960 to 1970 who sought to sustain Cambodia’s neutrality and was accused of supplying the National Liberation Front (NLF, or South Vietnam-based guerrillas) from a major guerrilla command center.

In 1970, the Nixon administration backed a coup that replaced Sihanouk—who had allied with the Khmer Rouge—with army officer Lon Nol.

White House tapes reveal that President Nixon told Secretary of State Henry Kissinger after the coup to “go in there and I mean really go in….I want everything that can fly to go in there and crack the hell out of them.”

After the conversation ended, Kissinger called General Alexander Haig, Deputy National Security Advisor, to relay the new orders from the president: “He wants a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia….Anything that flies on anything that moves.”

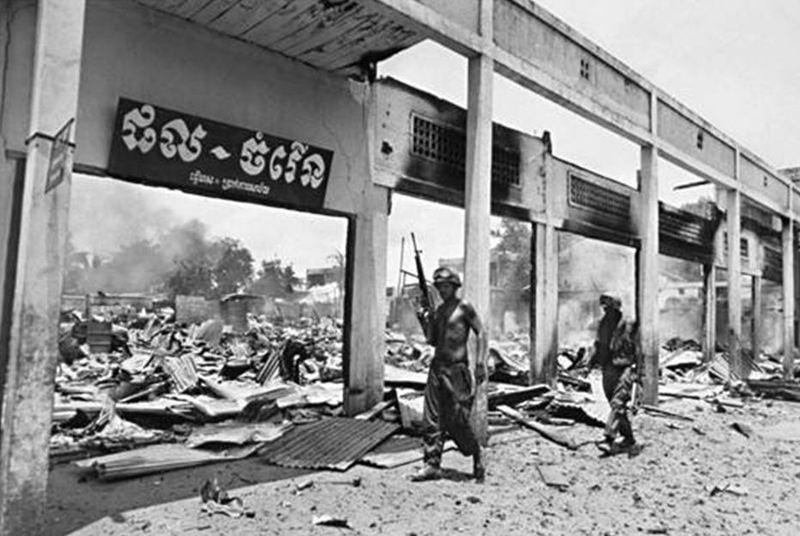

Killing an estimated 150,000 people and leveling countless villages, Nixon’s massive bombing campaign drove an enraged peasantry into the arms of the Khmer Rouge, who took retribution on Lon Nol’s supporters.

Chhit Do, a former Khmer Rouge official, noted that “the ordinary people sometimes literally shit in their pants when the big bombs and shells came. Their minds just froze up and they would wander around mute for three or four days. Terrified and half crazy, the people were ready to believe what they were told. It was because of their dissatisfaction with the bombing that they kept on co-operating with the Khmer Rouge, joining up with the Khmer Rouge, sending their children to go off with them.”

Over the course of the Indochina War, the U.S. dropped 500,000 tons of bombs over Cambodia—more than the combined weight of every man, woman and child in the country.[3]

Many bombs were cluster munitions which had a high dud rate, or gravity bombs that failed to detonate when they hit soft ground. In northeast Cambodia, as many as 80,000 air-dropped cluster munitions containing 26 million bomblets remain unexploded.[4] About 738 square miles of land in Cambodia are contaminated.[5]

This has created a great hazard for people who are afraid of triggering the bomblets. Lokkru Kheang, a teacher from Koun Mom District in Ratanakiri Province told Lin that, during certain weeks, he hears bombs going off on a daily basis.[6]

Another woman, Pom, told Lin about her 15-year-old cousin who found a cluster bomb in the stream where he used to bathe and struck it too hard with a stick, causing it to explode. The boy lost his hand and a fragment was lodged in his head, resulting in his death.[7]

Sadly, every Lao and Tumpuon that Lin interviewed could recall a story in which a friend, family member, or acquaintance was injured or had died from unexploded bombs. The gruesome accidents were spoken of as if they were almost routine—a normal hazard of life.[8]

Lin suggests that, because of fear of the bomblets, many farmers cannot maximize their land usage or experiment with new crops. The procedure they must follow is not to go into abandoned fields, to be careful in forests and overgrown areas, to keep a light footprint and to beware of stray objects.

Because of the hazards, farmers in heavily bombed areas during the Indochina War are still unable to “take advantage of modern agricultural machinery and innovations such as tractors, water pumps, and new types of commercial crops that require tillage,” according to Lin.[9]

Large numbers of unexploded bombs tend to cluster in the most fertile soil, causing farmers in these seemingly ideal areas to produce crops only at the subsistence level.[10]

One of the farmers whom Lin interviewed, Vannary Leng in Ratanakiri Province, said she could only work on a small piece of land because of the fear of the bombs, avoids crops like potatoes that require tilling even if they are profitable, and uses hand tools instead of machines so she can keep her eyes peeled for bomblets.[11]

Sam Oeurn, a village elder and former Khmer Rouge (revolutionary army) fighter, told Lin that he chose to plant a few cashew trees rather than grow cassava for commercial production because, if he did the latter, he would have to break apart his topsoil.[12]

Back in the war years, Oeurn told Lin, people in his village had to flee into the forest to hide from American bombers which would fire at any traces of smoke. They would then have to sneak back into the village and farm their fields at night in order to have food to eat.[13]

According to Lin, the net effect of all the undetonated ordnance remnant from that period is to stunt the Cambodian economy. Farmers in bombed, high-fertility areas end up producing 50 percent less rice and collect forty percent less income than their counterparts on non-bombed similarly fertile land.[14]

Lin writes that an undetonated bomb acts as a “time capsule, marking the place in time when development stopped. More than fifty years after the Vietnam War, affected farmers are still unable to safely take advantage of machinery or even the entirety of their land…The American foreign policy decision to thoroughly bomb a neutral country had a profound impact on the structure of its modern economy”[15]

Unfortunately, none of the policymakers responsible for the bombing has ever displayed any remorse or concern for the people whose lives were shattered by their decisions.

Nor have most academics, whom Lin criticizes for trying to sugarcoat or minimize the ravaging economic effects of American wars.

Fifty years after the end of the Indochina War, the U.S. continues to bomb sovereign countries and provide weapons for yet more bombing attacks that will continue to adversely impact people’s lives decades from now.

See H. Bruce Franklin, Vietnam and Other American Fantasies (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000). ↑

Erin Lin, When the Bombs Stopped: The Legacy of War in Rural Cambodia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024), 7. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 9. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 58. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 178. By comparison, land mines and unexploded ordnance contaminate only 280 square miles of land in Afghanistan, another war-ravaged country, and 15 square miles in Lebanon. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 59. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 106. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 107. People also told Lin how they became sick from toxic chemicals released by the undetonated bombs. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 28. ↑

Idem. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 62. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 66. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 104, 105. Oeurn joined the Khmer Rouge who he said came from the villages. He considers the Khmer Rouge to have been a revolutionary army defending the people from foreign attack. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 84. ↑

Lin, When the Bombs Stopped, 81. The only positive thing Lin notes is that the damaging presence of the undetonated ordnance has hindered the desire of predatory elites from taking over the land of poor peasants in the Cambodian countryside. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.” He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025). Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency . He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

The Trump administration has cancelled or halted most USAID to Cambodia, but it seems like China will be replacing this aid. China will especially be providing help clearing mines.

https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/in-cambodian-mine-clearance-china-replaces-usaid

Ordinance or Ordnance? There’s a big difference.

Ordinance = (1) a piece of legislation enacted by a municipal authority or (2) an authoritative order; a decree.

Ordnance = military supplies, especially weapons and bombs.

Yes, this article is correct.

The bombing of Cambodia began under President Johnson in 1965. It appears to have been on a small scale though compared to what happened under President Nixon.