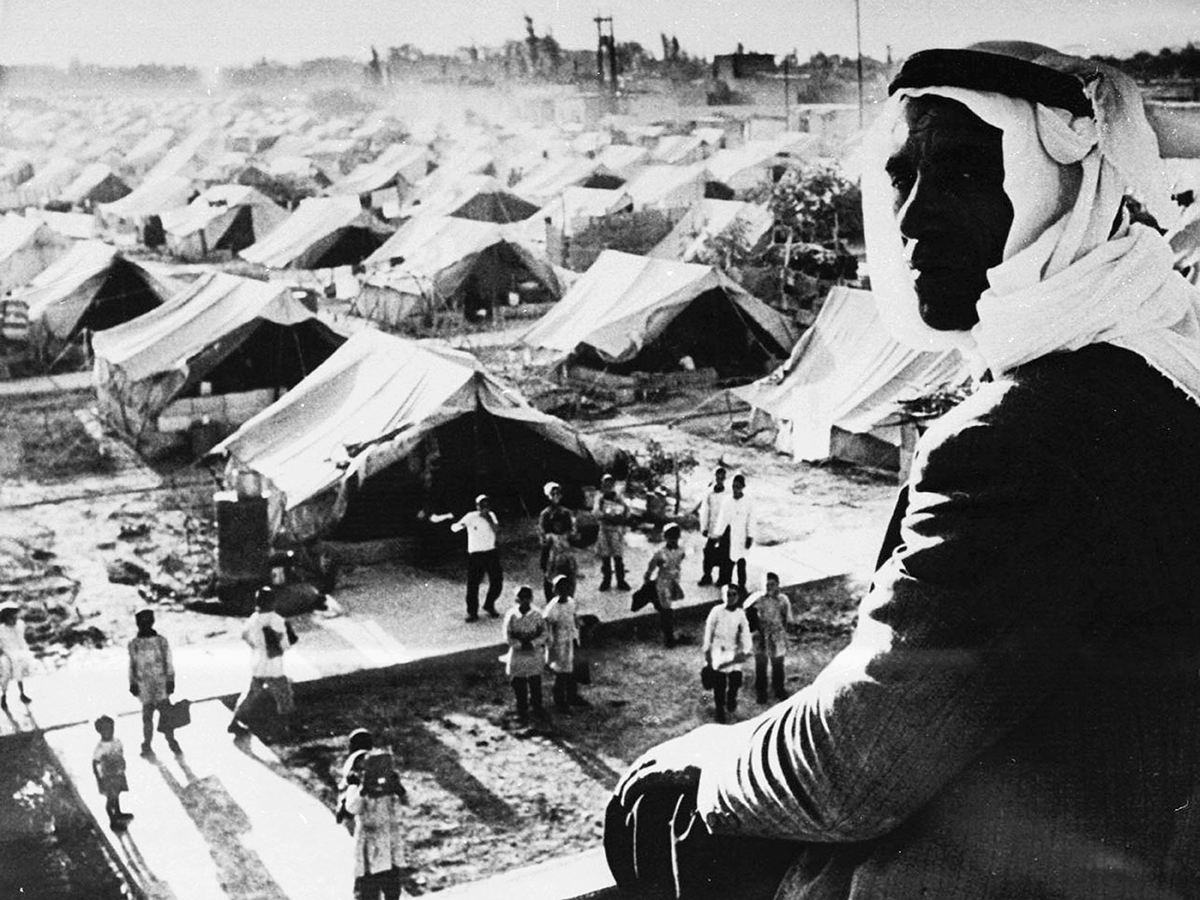

The ongoing genocide in Gaza has brought greater global attention to the plight of Palestinians, a huge number of whom have been refugees since the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 when they were expelled from their land in what is known as the Nakba.

The brutal Israeli onslaught over the last year and a half has contributed to a further deterioration of living conditions inside the envisioned state of Palestine—the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip—and outside it, where refugees are hosted under the UNRWA operations and elsewhere.

Recent events have underscored the necessity of empowering Palestinian refugees and ending their dependence on foreign aid organizations and NGOs.

Adding to their self-reliance would help decrease the huge despair and anger caused with a prolonged status of refugeehood and statelessness.[1]

Palestinian stateless refugees are considered a significant bulk out of the stateless persons around the globe.[2]

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) announced an international campaign in 2014, titled “I Belong,” and calling for resolution of existing major situations of statelessness by November 2024, applicable in principle to Palestinian stateless persons but with little effort paid on that front due to unattainable mutual negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian representations.

The plight of refugees, as noted, is closely related to the events of 1946-1948 and can be said to be of a protracted and continuous nature.

The events of voluntary and forced displacement and dispossession accompanying the succession of Mandate Palestine initiated the 1948 Israel-Arab armed conflict which has changed and turned over time along with the establishment of the International-law de jure state of Palestine into an Israel-Palestine international armed conflict associated with the 1967 armed conflict.

The challenges faced by Palestinian refugees differ from one context to another. The main problems include: limited access to social, cultural and economic rights; narrative fight over the Nakba displacement and related school education; work generation; higher education; inadequate housing; and poor infrastructure inside the camps.

In addition, they face a lack of public spaces, overcrowding, restrictions on camp expansion and land titleship outside the camp, and limited secondary health-care services, social marginalization, de-development, and heightened poverty inside the camps.

These multifaceted issues have resulted in increased violence and instability within the limited-space camps. The vulnerabilities of refugees have been compounded by internal events in host communities and events of violence, like in Syria, resulting in double refuge status. The challenges extend to political and civil rights, with Israel denying Palestinians their right to self-determination and for refugees to move on from their plight of statelessness and refugeehood.

On November 15, 2022, the Commissioner-General of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency in Palestine (UNRWA)-Jerusalem stated that 90% of Palestinian refugees in Syria and Lebanon suffer from “unprecedented levels of poverty.” Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini added that most Palestinian refugees (93%) in Lebanon live below the poverty line. He talked about the increasing needs in the refugee community, noting that 40% of UNRWA students “could not eat breakfast every morning.”

In 2012, then-President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Peter Maurer authored a law journal article, “Challenges to international humanitarian law: Israel’s occupation policy (icrc.org), in which he stated “Perhaps the most protracted and entrenched humanitarian situation in the region is the continued alienation of the Palestinian population living under occupation in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, or displaced in refugee camps across the region.”

Durable solutions

According to the UNRWA,[3] Palestinian refugees are defined to be “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”

This link with property and livelihood is directly concurrent with Resolution 194 (III) on compensation for titles lost between 1946 and 1948.

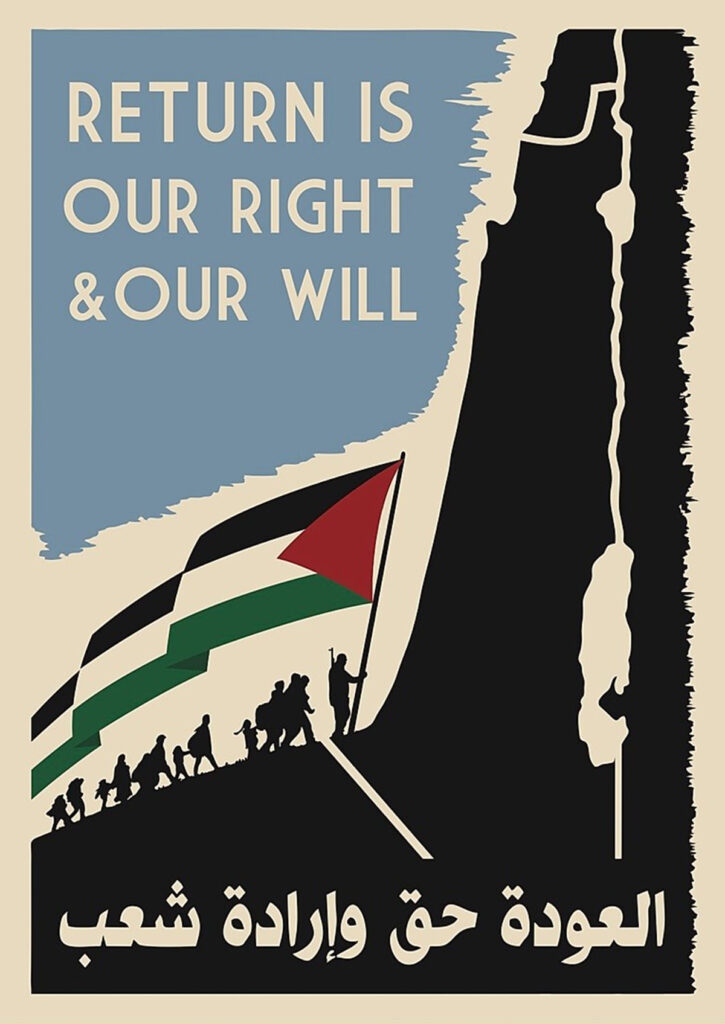

Durable solutions are pending final negotiations occurring between the parties to the armed conflict—Israel and Palestine. The durable solution highlighted by the Palestinian position is a just solution that relies on UN General Assembly resolutions with three-element reparations:

- recognition by Israel of the Palestinian refugees’ right to return to start the negotiations;

- restitution and, where impossible, adjustment to a form of assigning another vacant land in Israel; or

- in case of the preference of a refugee to receive compensation rather than “return,” to receive full and complete compensation on lost land and livelihood.

A companion for all options is to receive compensation for non-material damage in terms of mental suffering resulting from long displacement.[4]

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “the options for our refugees should be: return to Israel, return/resettlement to a future Palestinian state, integration in host states, or resettlement in third-party states,” all linked with compensation that its value would be assessed against the option of the single refugee.

(1) Return: The international fora have some examples on voluntary return of refugees to their original land. Chances for voluntary repatriation are reliable based on agreement made by the parties to the armed conflict during the conflict or post the settlement. An example of the latter is the case of non-international armed conflict in Burundi, which occurred between 1994 until 2005 and resulted in refugeehood in neighboring countries. The returnees into Burundi, after settlement of the conflict, are included within policies drawn for integration and empowerment set by the Directorate General for Repatriation, Resettlement, Reintegration of Returnees and War-Displaced Persons in cooperation with the UNHCR and UNDP.[5] The UNHCR role toward the Palestinian refugees is discussed below in the case of UNRWA.

(2) On the local integration and/or resettlement of refugees and fostering their inclusion into third countries conferring a citizenship,[6] local integration has been employed by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in relation to all Palestinian refugees, excluding Palestinian displaced persons in 1967 who are located inside the so-known Gaza Camp of which 88% of its residents are medically uninsured.[7] Nationality laws of different hosting countries to Palestinian refugees can contribute indirectly to the local integration. For example, on the small percentage of refugees in Egypt, those who were married to Egyptian females, the mothers can pass on their nationality to their sons and daughters, unlike the nationality laws of Lebanon and Syria.[8] About the re-resettlement of refugees into other countries other than the original hosting state, some Palestinian refugees have made their way to Europe, Canada, and elsewhere and received or are in the process of receiving a nationality that would end their stateless status, but were not compensated on losses sustained. The available countries’ mechanisms and the UNHCR can play a significant role in resettlement of Palestinian refugees into third-country options.

(3) There is some evolution of Palestinian pragmatism on the right of return with PLO showing options for return of refugees into the West Bank and Gaza Strip considering the fact that refugees are unwilling to submit themselves to live in an Israeli state.[9] In fact, the main problem of repatriation/return is that the refugees may not want to receive Israeli nationality. From that it can be inferred that the Israeli settlements in the West Bank representing big urban centers can have the potential to receive thousands of Palestinian refugees into the future Palestinian Sovereign State, allowing for Palestinian citizenship.

Having the right of return at the end of the day considered as an individual-based right under the inalienable collective right of return, any of the afore-mentioned options shall not jeopardize the right of compensation on titles and livelihoods lost and mental suffering. On that, the UN Conciliation Commission for Palestine concluded an identification and evaluation of Arab property in 1964 and it still retains land records of Arab owners defining the location and area of the property.

There is an international recognition that Palestinian refugees are entitled to their property and to revenue—income derived therefrom since then—in conformity with the principles of equity and justice under Resolution 194 (III).

It is important to mention that hundreds of Palestinians were displaced due to the 1967 armed conflict, many of whom were residing in UNRWA Areas of Operations. Like the Palestinian refugees of 1948, displaced persons of 1967 were guaranteed the right to return to their property based on UNGA resolutions and Article XII of the Oslo Declaration of Principles of 1993.

Status of Palestinian refugees, and roles of UNRWA, UNHCR and ICRC

The Palestinian refugees have a distinctive legal status under international law. The 1951 Refugee Convention and its protocol of 1967 excludes the application of the convention over Palestinian refugees registered under the UNRWA support by virtue of Article 1 (D): “This Convention shall not apply to persons who are at present receiving from organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection or assistance.”

The same holds true for the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons which literally repeats in Article 1 para. (2) (I), the quoted Article 1D above of the 1951 convention.

Therefore, the 1951 and 1954 conventions excluded Palestinian refugees supported by UNRWA from the scope of the two conventions and, as such, from the support that can be provided by the UNHCR, regardless of whether the hosting countries have ratified those conventions or not.

Knowing that the UNRWA areas of operations are the Gaza Strip, West Bank, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan are considered as de-facto stateless persons on the basis that they are not protected by the operation of any country and the fact that UNRWA does not, at the end of the day, provide a citizenship per se as it solely provides relief and assistance operations.[10]

The case is different for refugees acquiring a Palestinian ID number that allows them to reside, regularly, in their respective domiciles in areas of Gaza and the West Bank, or those given nationality in their respective hosting countries.

Doctrine 13 of the UNHCR speaks about the Palestinian refugees in areas of UNRWA operations.[11] The guidelines illustrate the interpretation of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention, the guidelines were made in cooperation with the UNRWA for the attention of governments, legal practitioners, decision makers, the judiciary, and UNHCR staff.

- Article 1D, para. 1, is considered an “exclusion clause,” while para. 2 is an “inclusive clause,” and the two should be read sequentially. [12]

- It was the purpose of Article 1D to show that Palestinian refugees are considered a sui generis class of refugees under the 1951 Convention until their position has been definitively settled in accordance with the relevant resolutions of the UNGA, and meanwhile to avoid duplications or overlapping between the UNRWA and UNHCR.[13]

- According to the doctrine, Palestinian refugees are defined as follows:

- Palestinian refugees within the sense of UNGA Resolution 194, para. III, and subsequent resolutions, encompassing all of those who were displaced from the part of Mandate Palestine which became Israel, and who have been unable to return there. Under UNRWA system, those are registered persons—persons who meet UNRWA’s Palestine Refugee criteria: 1948.[14]

- Displaced persons within the sense of UNGA Resolution 2252 (ES-V) of 1967 and subsequent UNGA resolutions and who, because of the 1967 conflict, have been displaced from occupied Palestinian territory and unable to return there, including those displaced due to hostilities up until 1982. Under UNRWA system, those are non-registered persons—persons eligible to receive UNRWA emergency services without being registered in UNRWA’s Registration System; 1967.[15] Having this category originally displaced from the envisaged Palestinian state located within the border of June 4, 1967, the main problem of this category is that in the two months following the armed conflict of 1967, the State of Israel (IL) conducted a census of the residents of the West Bank and Gaza, combining the Palestinian population registry. Any addition to the Palestinian population by the Palestinian Authority would need the IL consent to materialize the addition as per Article XII of the Oslo Accords and Article 28 of the Annex III.

- Descendants from original male and female Palestinian refugees and displaced persons of the 1948 and 1967 events.

All the above categories are excluded from the support of UNHCR with noting that the standard is the “eligibility,” not on whether they receive assistance from UNRWA at current or not for 1946-48.[16] This lock of UNHCR support adds on the legal impediments toward reaching durable solutions for refugees. In 2021, approximately 5.7 million women, children and men are registered with the Agency as Palestine refugees.

A further 700,000 persons are also registered with the UNRWA as eligible to receive services within the scope of 1967 displacement. It is important to flag that the non-registered persons of 1967 are eligible to access UNRWA services on the basis of need—as such in case of improved economic conditions, then they are no longer supported by UNRWA, and as such remain outside protection of UNRWA which would justify UNHCR involvement solely in the case of statelessness of the refugees.

UNHCR is to re-establish its mandate over the Palestinian refugees in the UNRWA areas of operations in the following scenarios:[17]

- Termination of the mandate of UNRWA by UNGA resolution—automatic alternative protection.

- Inability of UNRWA to fulfill its protection or assistance mandate.

- Threat to the applicant’s life, physical integrity, security or liberty or other serious protection-related reasons: individuals may be forced to leave area of UNRWA operation due to persecution, torture and CIHD treatment, human trafficking, and exploitation, forced recruitment, severe discrimination or arbitrary arrest and detention. Group threats involve armed conflict, civil unrest, OSV, the non-ability of the state to protect refugees.

- Practical, legal, and/or safety barriers preventing an applicant from (re)availing him/herself of the protection or assistance of UNRWA—case-by-case scenario.

In addition, it can be concluded that it is the primary UNHCR responsibility to address Palestinian de facto refugees and stateless persons under the 1951 and 1954 conventions who exist outside the countries in which UNRWA performs its operations, like in Egypt and Iraq.

It also holds true that the ICRC has within its mandate all refugees residing in the Occupied Palestinian territory, themselves being protected persons under the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.

“Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Persons of Concern,” UNHCR, May 2003. ↑

“Stateless Palestinians,” Forced Migration Review (fmreview.org) There are approximately seven million refugees world-wide; one in three is Palestinian, half of whom are stateless persons. Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, available at Refugees (mfae.gov.ps) ↑

UNRWA was founded in 1949 through UN General Assembly Resolution 302 at the conclusion of the Arab-Israeli conflict of 1948, aiming for “the alleviation of the conditions of starvation and distress among the Palestine refugees” ↑

UNGA Resolution 3236, para. 2: “Reaffirms also the inalienable right of the Palestinians to return to their homes and property from which they have been displaced and uprooted, and calls for their return.” See also UNGA Resolution 194 (III), para. 11, on the right of return and compensation: “Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.” ↑

“2021 Burundi Joint Refugee Return and Reintegration Plan, January-December 2021. ↑

“Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Persons of Concern.” “This includes the three traditional durable solutions of voluntary repatriation, resettlement and local integration, as well as other local solutions and complementary pathways for admission to third countries, which may provide additional opportunities.” United Nations, “Global Compact on Refugees EN.pdf (globalcompactrefugees.org) (2018). ↑

Division of Refugees Affairs – Hamas, 2015. ↑

Citizenship Rights in Africa Initiative, May 2011, “Post-Revolution, Egypt Establishes the Right of Women Married to Palestinians to Pass Nationality to Children,” May 13, 2011. (citizenshiprightsafrica.org) ↑

“For his part, the Palestinian PNA President, Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen), acknowledged that a massive repatriation of the refugees to Israel would destroy the country: return to Palestine would thus chiefly concern the territory of a future Palestinian state, limited to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and living in peace with Israel.” “Palestinian Refugee Issue After Oslo Agreements,” September 11, 2015 (fanack.com) See also Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Refugees (mfae.gov.ps) ↑

The term “stateless person” means a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law according to the 1954 Convention. Art.44 of the GCIV defines refugees as those who do not enjoy the protection of any government. The 1951 Refugee Convention defines refugee under introductory norms to be “A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country” [NOTE: The term “stateless” was first used on page 1 and throughout the article. Why is the definition here instead of near the front?] ↑

Guidelines on International Protection No. 13: Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/legal/5ddfca844/guidelines-international-protection-13-applicability-article-1d-1951-convention.html ↑

Article 1D states:

This Convention shall not apply to persons who are at present receiving from organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection or assistance.

When such protection or assistance has ceased for any reason, without the position of such persons being definitively settled in accordance with the relevant resolutions adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, these persons shall ipso facto be entitled to the benefits of this Convention. ↑

Paragraphs 6 and 7. ↑

Consolidated Eligibility and Registration Instructions (CERI) for refugees – UNRWA regulations – Question of Palestine. The following documents may be presented as proof that elements of UNRWA’s Palestine Refugee criteria, main mandate, are met: • Palestine passport issued prior to 15 May 1948 indicating that the applicant was resident in Palestine during the period between 1 June 1946 and 15 May 1948. • Birth certificate issued in Palestine before 15 May 1948. • Marriage certificate issued in Palestine before 15 May 1948. • Identity card issued in Palestine before 15 May 1948. • Employment certificate issued in Palestine before 15 May 1948. Receipts of water, electricity, telephone, radio, taxes or other official documents indicating residence in Palestine before 15 May 1948. • Land registry documents concerning property in Palestine (“tabbo”) issued by the Department of Land in Palestine before 15 May 1948. • Documents showing registration of close relatives with UNRWA (paternal side only). • Red-Cross registration card issued between 15 May 1948 and 1 May 1950. • UNRWA registration Fact Sheet. • UNRWA Punch Card (Ex-code). • Any other documents endorsed by an official authority in Palestine before 15 May 1948. ↑

Ibid., page 7 – mandate of UNRWA in relation to the 1967 displaced persons: “to continue to provide humanitarian assistance, as far as practicable, on an emergency basis, and as a temporary measure, to persons in the area who are currently displaced and in serious need of continued assistance as a result of the June 1967 and subsequent hostilities.” (Emphases added.) ↑

Footnote 11, para. 26 and para. 27. ↑

Footnote 11, para. 22. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Khalil Al-Wazir is a Palestinian from Gaza now living in Egypt.

He is an attorney with an LLM from the University of Pittsburgh School of Law and served as a legal adviser for the International Committee of the Red Cross in Gaza from 2017 until he was forced to leave due to the war in June of 2023.