[This is the second of a two-part article. Part I is available here.—Editors]

Obstacles to Change

Attempts to change the United States immigration system faces the serious problem that the current system is a very lucrative business for some powerful interests. Corporations benefit with an influx of cheap labor into the U.S.

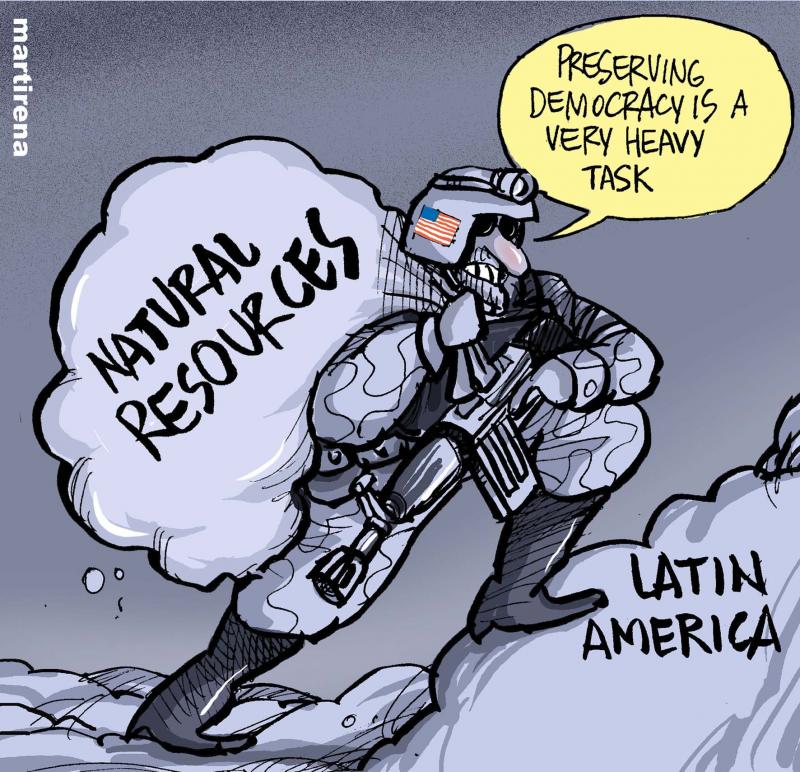

Corporations also benefit in countries where they are free to pursue the unregulated extraction of resources at the expense of the lives and communities of local people. Politicians benefit from supporting these corporate interests and by portraying immigration as a threat and themselves as the only ones able to turn back the threat.

Foreign governments benefit when immigrants send back remittances (money) to folks at home. In the past few years, Hondurans in the U.S. have sent back to families in Honduras an average of four billion dollars each year, a sum that represents nearly 20% of the Honduran national income.

The U.S. government has been contracting with private prison companies to hold undocumented immigrants in detention in prison-like conditions while the immigrants await a hearing or deportation. Such companies are paid thousands of dollars per year for each detainee.

The companies have an economic interest in holding as many detainees as possible in as cheap (i.e., shabby) conditions as possible. This practice has been criticized and condemned by international human rights agencies, and groups of U.S. citizens have made efforts to end the use of private prisons for undocumented immigrant detention.

Beyond the legal and quasi-legal sphere, other interests benefit from a large flow of immigrants. Private “guides” (coyotes) charge thousands of dollars with the promise of guiding individuals and families safely into the United States. Families often sell anything they have or even go into debt to finance this “safe” guidance, only to be abandoned along the way by the coyote who absconds with the fee.

Criminal gangs and powerful drug cartels also threaten and prey on vulnerable immigrants, forcing them to carry drugs into the U.S. or risk the kidnapping or death of family members. Adding insult to injury, politicians such as Donald Trump use reports of this to blame the victims by portraying the immigrants themselves as the drug traffickers or simply as attracting criminal gang activity.

In addition, immigration is a foreign policy propaganda tool. The U.S. uses immigration as a propaganda weapon against its “enemies,” countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua. In the past few years, U.S. agencies have engaged in an active campaign to lure Nicaraguans to the U.S. with promises of legal documentation and work. One purpose is to increase the flow of emigration out of Nicaragua and to claim that the emigration is due to oppressive conditions created by the Nicaraguan government.

Nicaragua has had a policy of allowing migrants from other countries to pass through Nicaragua on their way north, a practice that was grossly mis-characterized by U.S. officials as “human trafficking.”

This accusation may seem hypocritical if one considers the many ways in which the U.S. uses immigration and immigrants for its own economic and political purposes, its own form of human trafficking. Economic sanctions against Venezuela and Nicaragua are meant not only to weaken the economies of these countries, but also to promote emigration that can be portrayed as people fleeing oppressive regimes when, in reality, many people are leaving because U.S. sanctions have worsened economic prospects in their countries.

Changing the current immigration system also faces the intractable problem of imperial addiction. For more than a century, the United States has become dependent on acquiring and controlling an array of countries, mostly in Latin America, as sources of wealth and resources. This “colonial” system is deeply entwined with an image of what the U.S. standard of living and “spread of democracy” should be.

Resources of Heart and Mind

Some claim that making the U.S. immigration system more humane and less punitive will only serve to encourage more people to immigrate to the U.S. This argument seems to assume that people make decisions about migrating based on how receptive or exclusionary U.S. policy appears. In fact, people decide to emigrate for a variety of reasons, and do not always have the luxury of waiting for the U.S. to be receptive.

Emigrating is so much of a life and survival act for many that, for most immigrants, both the dangers of the journey and uncertainty about how they will be received seem preferable to remaining in an untenable situation at home. It is often difficult for those who have never been in such a situation to understand this logic of survival. Creating sustainable and self-reliant conditions at home is a better and more direct way to influence migrants to decide to remain at home.

U.S. citizens have various ways to affect the immigration system and make it more humane, and even to help reduce the need for emigration. Many people are involved in groups that provide direct material and other assistance to both documented and undocumented immigrants, without differentiating. The assistance ranges from providing shelter and necessities to enabling legal defense for immigrants, especially asylum seekers. Individuals and groups can also counter the most offensive stereotypes of immigrants by emphasizing the positive contributions of immigrants to local communities where they live.

U.S. citizens can also encourage and support actions in Congress for change, including how immigrants are treated and legally processed when they arrive, guarantees for their rights, ways for the U.S. to assist governments in reducing corporate influence and corruption over foreign governments, and even attempts to call attention to the fundamental imperial or colonial ideology that underlies much of the immigration “problem.”

To that end, Representative Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) introduced Resolution 943 into the U.S. House, a resolution to abrogate and reject the Monroe Doctrine that has been the basis for much of U.S. policy in Latin America. This calls for a major change of mind and heart, but it comes with a list of specific measures that Congress can take. It is perhaps doubtful that the new Congress incoming in January 2025 will consider, much less pass, this resolution or, if passed, will implement its recommendations. But the very fact that it is there, in public, and boldly stated, gives us all a place to stand, a program to demand.

In some colleges and universities, faculty members, student groups, groups of scholars, and some administrators are working to defend undocumented students from detention and deportation. They can call upon several features of university culture to assist them. The university itself as an institution has long had a quasi-sacred aura about it. Many major U.S. universities were founded by religious denominations, often beginning as schools of ministry, and there is a cultural taboo against government interference in the life of the university, including a taboo on police or military presence on university campuses—a taboo that is quite often violated.

Universities and colleges are legally bound to confidentiality in not publicly disclosing the identity or presence of individual students registered in classes. There is a tendency among faculty not to ask which students might be undocumented. Although none of these safeguards is fully reliable, together they suggest that it should be difficult for government agents to enter campuses to identify and detain undocumented students. But universities are also businesses that are vulnerable to government pressure.

Non-participation is an old and widely used form of resistance to inhumane conditions and policies. It can take many forms. It is one of what anthropologist James Scott called “weapons of the weak.” Non-participation can mean withdrawing support from some part of a large, powerful and oppressive or illegal situation or regime. Mohandas (Mahatma) Gandhi and a large group of villagers in India provided one of the classic examples of non-participation—the so-called Great Salt March. The British colonial rulers of India imposed a tax on salt, a necessary item of diet. The tax helped to fund continued British rule.

As one way to weaken imperial rule and promote Indian independence, Gandhi led a march of several hundred miles to the sea where people made salt from sea water, bypassing the need to buy salt and pay the salt tax. This act was illegal, and people risked arrest and beatings. But non-participation does not have to be illegal or particularly risky. Today, some local and state police and law enforcement agencies in the United States have been instructed or have decided not to cooperate with federal agents in identifying and detaining immigrants. Non-participation of this sort would certainly make mass round-ups and deportation of immigrants more difficult.

Sanctuary

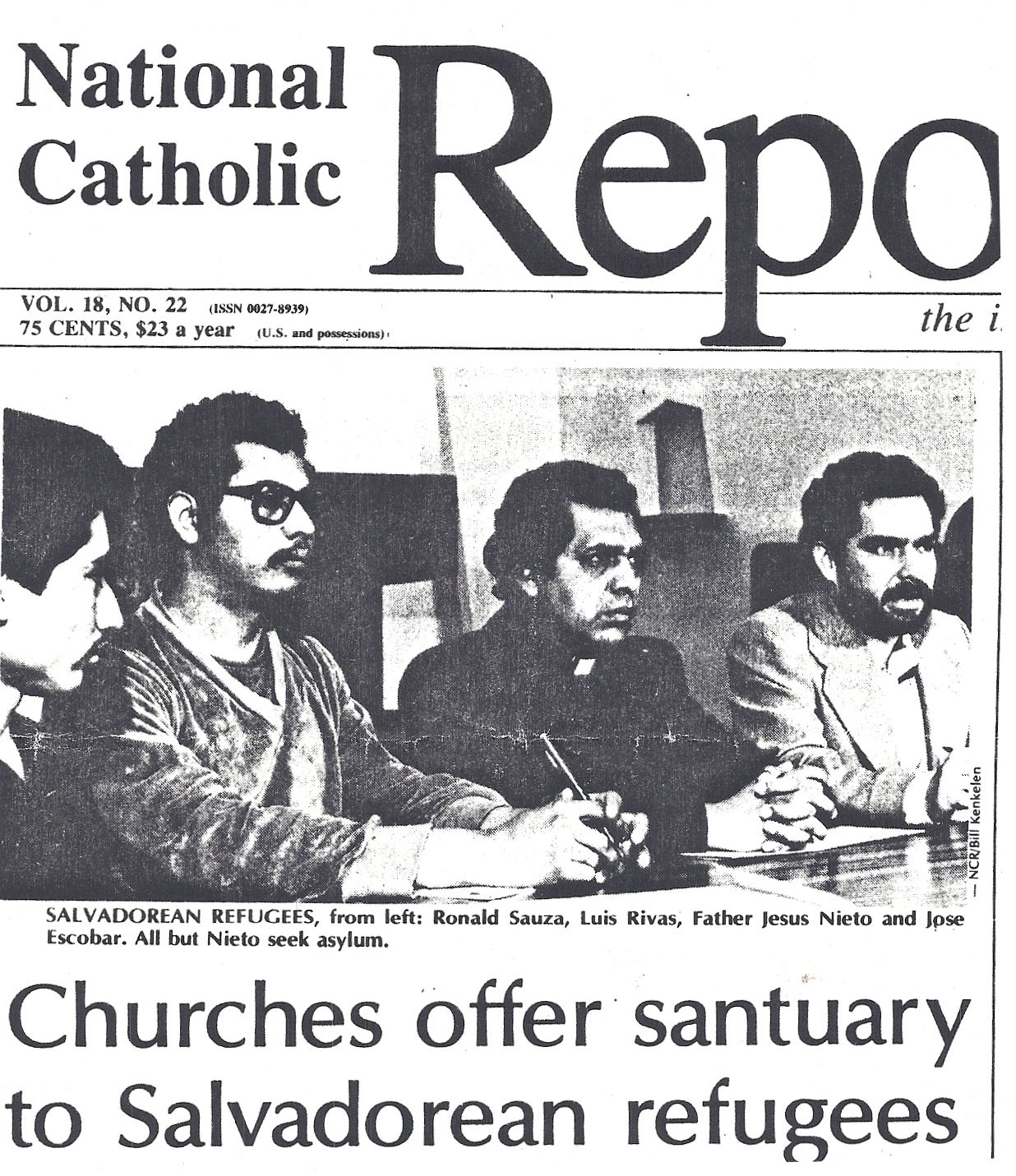

The so-called Sanctuary Movement of the early 1980s provides an important example for today. In the early 1980s, Central America was immersed in several deadly conflicts. In Nicaragua, the Reagan administration had promoted the Contra War that claimed 30,000 lives. In Honduras, those who controlled the government—the military and wealthy entrepreneurs—reacted to the Nicaraguan revolution of 1979 by enforcing the most oppressive measures of a national security state.

In El Salvador, the government and the military waged war against the FMLN guerrilla movement and anyone they thought supported it, including especially priests and other leaders of the Catholic Church. In Guatemala, the military in the early 1980s engaged in a genocide against the Mayan population (more than half the country’s population). People fled the violence, many finding their way to the U.S. with no time or ability to procure legal documents. This tide of immigrants was an embarrassment to the Reagan administration that had promoted the conflicts that forced the immigrants to flee Central America.

As individuals and groups in the U.S. began to offer material assistance and safety to the undocumented Central Americans, the Reagan administration resorted to mass deportations, coupled with legal punishments for those who helped immigrants. People were arrested for providing shelter to immigrants, for transporting immigrants to safe houses, for helping them cross the border. As more U.S. citizens began to assist, the penalties for assisting were increased.

Ancient Judaism demanded that the stranger and those in need be welcomed. In ancient Greece and some other parts of the Mediterranean world, sacred temples, groves of trees, or other places were held to be places of sanctuary for anyone fleeing—slaves, people accused of crimes or of unpopular political opinions, others. In Medieval Europe, certain churches and abbeys were considered places of sanctuary for those fleeing persecution from the king or civil authorities. Sanctuary became one aspect of the tension between the powers of church and state. Throughout much of its history, sanctuary was bound to the idea of divine protection.

Starting in places like Tucson, Arizona, church congregations began to revive the ancient concept of sanctuary. In the U.S. in the 1980s, churches and religious congregations contemplating sanctuary for the newly arrived immigrants faced the prospect of legal liability, facing criminal proceedings, revocation of their tax-exempt status, or other expensive penalties? Church councils debated this risk against their duty to protect the church and its pastors from harm. It was an ethical and moral question.

Maybe the scene of police or military entering a house of worship to drag out immigrants would be too embarrassing, and would dissuade the authorities from breaching sanctuary, especially if it seemed to violate First Amendment religious freedoms. Would local law enforcement authorities refuse to participate in such a removal? Declaring sanctuary for immigrants in the early 1980s was, indeed, a leap of faith for both the immigrants and their protectors. The motives of those who offered sanctuary seemed to include the demands of their religious faith, the demands of simple humanity, and the political need to resist what seemed to be a repressive situation and the authorities who had created it.

The Sanctuary Movement of the early 1980s began as individual acts but soon developed some coordination and planning. This was important to offer support to those contemplating assisting the immigrants. Since the 1980s, churches and religious congregations in different parts of the U.S. have occasionally offered sanctuary to individuals and families. Is some adaptation of the Sanctuary Movement of the 1980s a model or an option going forward?

The Necessary Defense

In Sanctuary: A Resource Guide for Understanding and Participating in the Central American Refugee Struggle (New York: HarperCollins, 1985), the volume’s editor, Gary MacEoin, writes:

In Burlington, Vermont, 16 November 1984, a jury unanimously acquitted twenty-six citizens of trespass charges. They had admitted refusing to leave Senator Robert Stafford’s office. But, they argued, the U.S. government is violating international law in Central America, the President has lied about why he is supporting a covert war in Nicaragua, and they as citizens had exhausted all less confrontational means to get elected officials to correct the situation. The defendants thus successfully invoked the time-honored, though seldom applied “necessity defense” doctrine: a minor law (here, trespassing) yields to a major imperative (prevention of war crimes and of violating the U.S. Constitution).

The necessity defense is a legal doctrine, a statement of priorities, and a moral judgment. It may be a useful legal protection for those who challenge some of the worst aspects of the coming attack on immigrants. As a statement of priorities, it demands clarity about what is at stake in the lives of human beings. It also invites others to see more clearly, as the Vermont jury apparently did. As a moral judgment, the necessity defense brings us to the heart of our current situation. What is demanded of us is to discern clearly and to promote the greater good amid all the imperial debris, distractions, and temptations that the coming years will bring. This is a time to remember the necessity defense and for community discernment and action.

These are only a few of the resources that may become important in the coming struggle to protect both immigrants and the rest of us from dehumanization.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

James Phillips is a cultural and political anthropologist with forty years as a student of Central America.

His major concerns are movements of social change, political conflict, human rights, colonialism, and immigrant and refugee populations.

He is the author of articles and book chapters on Honduras and Nicaragua. His most recent book is Extracting Honduras: Resource Exploitation, Displacement, and Forced Migration (Lexington Books, 2022).

James can be reached at anthrodocjp@gmail.com.

This article was exceptionally well written until I came to the following comment:

“U.S. agencies have engaged in an active campaign to lure Nicaraguans to the U.S. with promises of legal documentation and work. One purpose is to increase the flow of emigration out of Nicaragua and to claim that the emigration is due to oppressive conditions created by the Nicaraguan government.”

In fact the Authoritarian Government of Ortega was in fact a significant factor as well described in this article:

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/record-emigration-nicaragua-crisis