With little variation, as it was 60 years ago, Brazil’s military and political elite, as well as its big business sector—namely agribusiness—are not fond of what could remotely be perceived as progressive, left-wing politics.

God forbid their country, harboring Portuguese colonial heritage in every nook and cranny, despite failing to eliminate First-Nation Indigenous populations, ends up like Cuba.

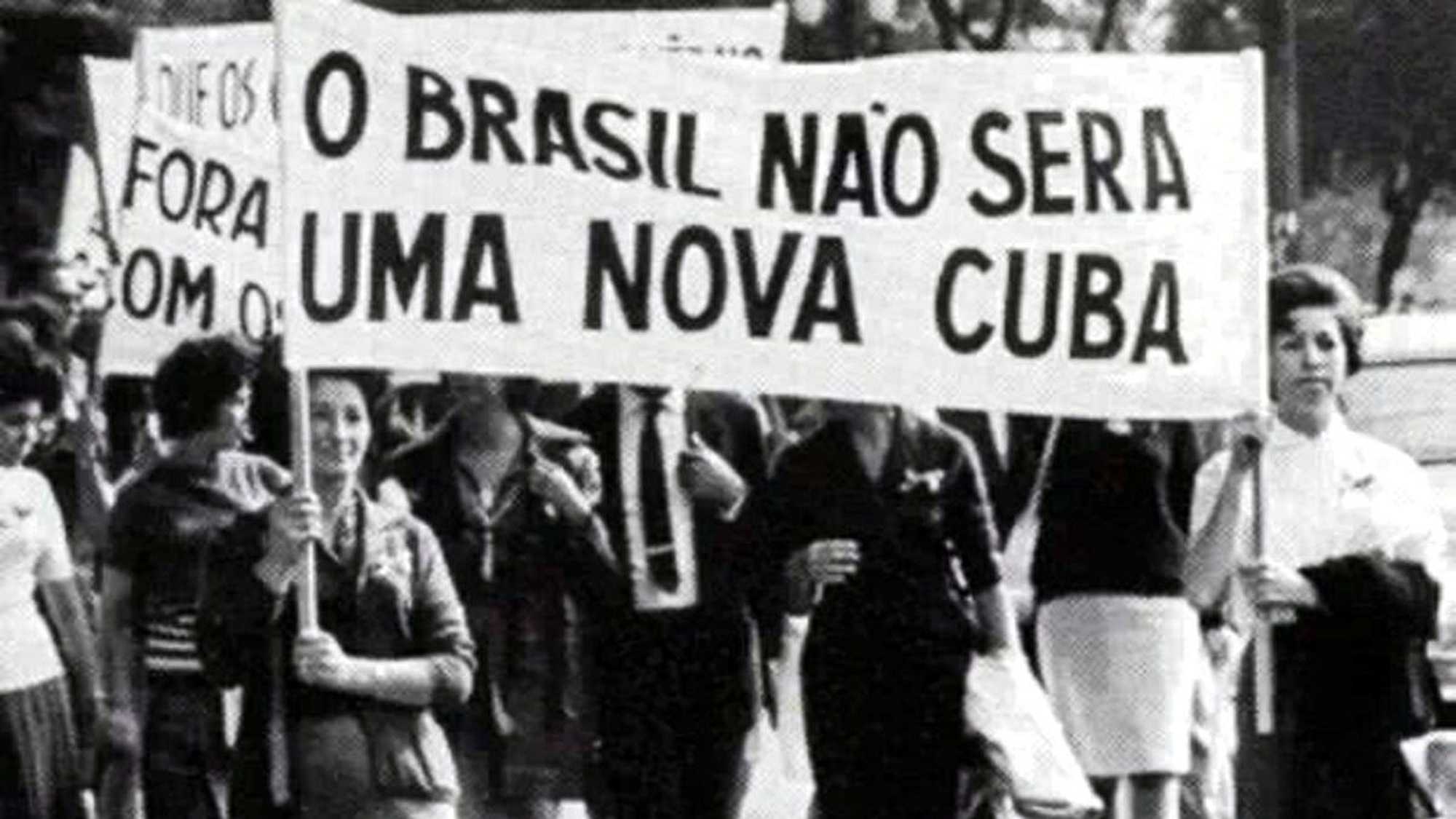

The phrase in the cover image is no stranger to repetition in these times. In 2021, former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro posted on Twitter those exact words: “Brazil will not become the latest Cuba.”

Earlier this month, Bolsonaro’s son and congressman, Eduardo Bolsonaro, stated in an interview that “Brazil will become the next Cuba if we fail to act now.” Despite the open hostility, the Caribbean island maintains hundreds, if not thousands, of medical personnel throughout Brazil to mitigate its lack of doctors and nurses working in poor and difficult-to-access regions.

Back in 1964, discontent erupted over proposals from democratically elected President João Goulart (Jango) aimed at extending the vote to the illiterate class in Brazil and fulfilling the promise of land reform. The response? On March 31 of that year, tanks and soldiers emerged from their barracks in Minas Gerais en route to the neighboring state of Rio de Janeiro.

Military personnel also took up strategic positions with their bellicose hardware in the capital, Brasília, and elsewhere in the country to halt what was propagandized by the media, religious and civil society groups as being “communism,” otherwise, the “domino effect.”

In the context of the Cold War, this coalition of anti-democratic forces included the U.S. government and its intelligence agencies. “Do everything that we need to do,” said President Lyndon B. Johnson, in reference to providing support for the coup once it had started.

This included Operation Brother Sam. Headed by the U.S. Marines, foreign assistance was unneeded as resistance to the coup within Brazil was neither organized nor strong enough to prevent its movement.

Three days after the coup was under way, on April 2, 1964, Auro Moura Andrade, Brazil’s congressional leader, falsely announced the “vacancy” of the presidency. Brazil’s constitution of that time stated that the presidency can only be considered vacant had the head of state been outside of the national territory. However, Jango had flown from Brasília to the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul, believing that he could rally support there against the coup plotters and operatives.

Less known about Brazil’s 1964 coup, unlike the U.S. tentacles of Operation Condor, which spread throughout the region, was Britain’s role in fomenting distrust and animosity toward Jango’s government.

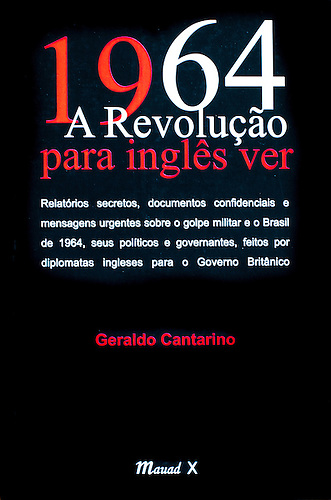

I reached out to Geraldo Cantarino, author of six books that deal with Britain’s meddling in Brazilian politics during this period, which culminated in a 20-year military dictatorship. His most recent publication, Geisel em Londres: A Visita De Estado Em 1976 E A Questão Dos Direitos Humanos (Geisel in London: The 1976 State Visit and Questions About Human Rights) was a finalist for the 2024 Vladimir Herzog Journalism Prize for Amnesty and Human Rights. An accomplished international journalist with stints at Visnews (Reuters), TV Bandeirantes, Multirio, Globo Ciência, as well as co-creator of the educational TV channel Canal Futura and a professional photographer, Cantarino is an active member of the Brazilian Press Association (ABI).

Julian Cola (JC): What was the impetus of your interest in the links between the British government and the overthrow of Brazilian President João Goulart (Jango)?

Geraldo Cantarino (GC): In 1996, I was studying in England when my uncle asked me to consult some documents in the Public Record Office (PRO), which is presently known as The National Archives. Located in Kew, on the outskirts of London, it houses the UK government’s official archives. My uncle had read the book titled Nitroglicerina Pura (Pure Nitroglycerin) by journalists Geneton Moraes Neto and Joel Silveira (Brazil: Editora Record, 1992) and was interested in a few topics they addressed. As I began to collect the data for his research, I noticed that documents related to the first year of the military-civilian coup of 1964, which overthrew the government of President João Goulart had been released for public review. It included a collection of correspondence and reports written by British diplomats in Brazil and other countries forwarded to the British Foreign Office in London. This subject has always piqued my interest: firstly, as I was born in 1964; secondly, due to family accounts about this dramatic period in Brazil’s history. So it was one of those opportunities that arose from being at the right place at the right time. I began looking closely at those documents and my first book, 1964: The Revolution for the English to See (Brazil: Mauad X, 1994), resulted from this initial research.

JC: How did these secret documents come to be declassified?

GC: In 1996, the British archive adopted a policy of retaining government documents for a minimum period of three decades known as the 30-year rule. So documents related to Brazil’s 1964 coup could only be made available to the public in 1994. This actually did not happen until 1996, 30 years after the military takeover in Brazil. Subsequently, in 2013, the British government initiated a new policy to release documents 20 years after their creation. However, it is important to remember that, when we research public archives, not all that happened was documented. Also, everything that was documented was not necessarily preserved. Everything that was preserved was not necessarily made public. And everything that was made public was not necessarily made available in its entirety and part of what was withheld may never be released. We should take this into account when consulting and processing those documents. The available archive represents just a fraction of the total. Consequently, we are dealing with fragments of a historical period which demands great attention.

JC: What were Britain’s interests?

GC: First, it is necessary to consider the historical context of the Cold War at the outset of 1960. The Cuban Revolution [1959], which ushered into power a socialist government in a Latin American country, was still a recent event. Besides that, the UK was always allied with the U.S., a country with which it maintains a “special relationship” to this day. There was, therefore, a concern throughout the Western World to monitor and contain the spread of socialist or communist sentiments, or any sympathizing tendencies for socialist reforms in the region. Naturally, behind these ideological preoccupations lay commercial and economic interests as well. Aligning with the Western mindset would facilitate and guarantee British business in Brazil. At the end of the day, it had more to do with the market as opposed to ideology.

JC: Speak about the origins of the Instituto de Pesquisa e Estudos Sociais [Institute of Social Research and Studies—IPES] and how this organization functioned to destabilize Brazil’s government.

GC: Established on February 2, 1962, IPES was an organization created by businessmen in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo dissatisfied with inflation, the lack of government planning, and an increase in state intervention. It represented the business sector’s reaction to what was perceived as left-wing tendencies upon national politics, supposedly influenced by communists. Officially, IPES emerged with the mission of studying national problems and framing them within democratic bases. Structured in the mould of a think tank, it sought to foment favorable political conditions capable of benefiting select corporations. In practice, the institute wove an influential network of power relationships and developed intense anti-government and anti-communist propaganda via leaflets, books, films, educational courses, public conferences and news articles. This propaganda emphasized the advantages of a democratic regime and free initiative, while at the same time associating communism to Jango’s government proposals. To structure and undertake its activities, IPES received donations amounting to millions of dollars from national and international sources, mainly from North America, to finance a political project in Latin America. Hence, it can be affirmed that IPES played a significant role in articulating what eventually culminated in the 1964 coup in Brazil. The institute operated as a center of influence concerning Brazilian society, promoting activities of political indoctrination, popular mobilizations, and conspiring against President João Goulart’s government, thus, contributing to his overthrow.

JC: What was the Information Research Department [IRD] and how did it collaborate with IPES?

GC: The IRD was a secret unit of Britain’s Foreign Office. Established in 1948 and discontinued in 1977, the IRD coordinated Britain’s anti-communist propaganda affairs during the Cold War. Its principal goal was to counter Soviet propaganda and the influence of communism throughout the world. Helping to disguise the true nature of its work, meant to remain strictly confidential, was its generic name. The primary role carried out by the IRD was to disseminate what was referred to as “gray propaganda” via books and articles published in the press. This propaganda was based on biased information without an identifiable source aimed at attracting attention or confusing the target audience.

In the opinion of specialists, IRD became an instrument that generated news that contaminated the well of journalism and fooled newspaper and book readers about global events. For nearly 30 years, IRD conducted a covert propaganda war with the objective of influencing British and international public opinion. In Brazil, the IPES was considered to be a reliable channel for distributing anti-communist IRD material in Portuguese. For that reason, good working relationships were maintained between the two institutions. Secret reports and documents that I reviewed in Britain’s National Archives demonstrate that secret operations from the British embassy in Rio de Janeiro were undertaken to produce and circulate IRD books in Portuguese. This was done in partnership with IPES, which distributed a large quantity of British materials via appropriate channels. For example, two booklets produced by IRD in London about Cuba were published as a book in Portuguese with the title Cuba: Nação Independente ou Satélite? [Cuba: Independent Nation or Satellite]. More than 5,000 copies of this publication were distributed free of charge by IPES.

The groundbreaking research that I conducted at Britain’s National Archives about IRD operations in Brazil resulted in the publication of Segredos da Propaganda Anticomunista (Anti-Communist Propaganda Secrets) [Brazil: Mauad, 2011].

JC: What was the União Cívica Feminina [Feminine Civic Union—UCF] and how did IRD assist this movement to mobilize protests against Jango’s government?

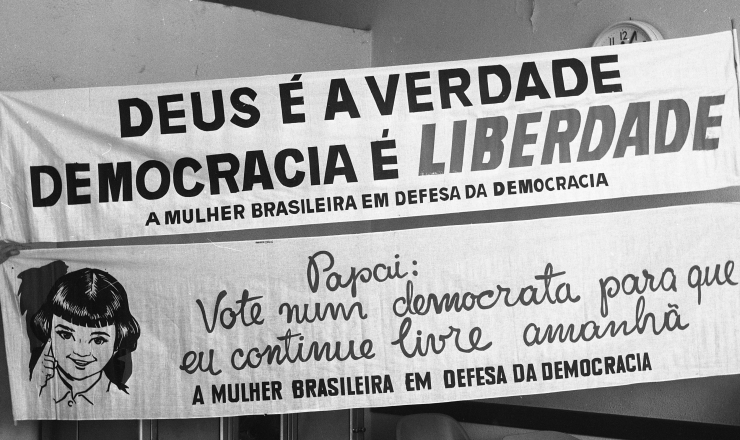

GC: The UCF was a Catholic movement in opposition to João Goulart’s government which started in São Paulo in 1962. Together with other civil society groups, such as Campanha da Mulher Pela Democracia [Women’s Campaign for Democracy—CANDE], the UCF participated in organizing the Marcha da Família com Deus Pela Liberdade [Family March with God for Freedom], the first large manifestation of right-wing groups in Brazil on Avenida Paulista in São Paulo on March 19, 1964, a few days before the military-civilian coup.

According to documents reviewed at the British National Archives, IRD’s propaganda material was frequently distributed to women organizations, including the UCF, in 1963 and 1964. According to political scientist René Armand Dreifuss, in his book 1964: A Conquista Do Estado — Ação Política, Poder e Golpe De Classe (1964: The Conquest over the State—Political Action, Power and Class Coup) [Brazil: Vozes, 1981], the IPES funded, organized, and oriented the three main women’s organizations in Brazil during those times: the UCF; CANDE; and Campanha para Educação Cívica (Campaign for Civic Education—CEC). In the UCF’s case, Dreifuss described it as being an organization dedicated to “clarifying” public opinion in “defense of the democratic regime” and to “awaken the civic consciousness of women,” represented by the propaganda face and machine led by IPES. Their right-wing concepts were disseminated via lectures, conferences, and basic indoctrinating educational courses intended for housewives and working women.

Robert Evans, an IRD official stationed in Brazil, gloated that the UCF “played a leading role in recent events”

after being “fed with a steady diet of IRD material for over a year.” J. MacKinnon, a British embassy offical

concurred, stating that “women played a vital role in the April 1 revolution.” (NOTE: To this day, those who stand

by Brazil’s 1964 military coup commonly refer to the takeover as a “revolution” against the threat of

communism.) [Source: SãoCarlosAgora.com]

JC: In what other ways did the Catholic Church contribute to disseminate fear toward Jango’s government among the public, which brought large crowds onto the streets demanding freedom?

GC: According to Robert Evans, a Foreign Office Field Officer who was specially trained and dedicated exclusively to the IRD’s activities in Brazil, the Catholic Church’s role in the anti-communist campaign in the country was likely the most significant, with the greatest potential to be sustained and effective. In his view, the Church demonstrated, for example, “the most intelligence in its attempts to redeem the youth from their Marxist tendencies.”

On 18 May 1962, Evans sent a secret document to the head of the IRD in London detailing the progress of his contacts with Catholic church organizations, expressing his view that these groups should start receiving select IRD publications. In another document, the annual 1962 report, he also mentions contacts between British officials and church leaders. The prevailing idea was that the church functioned so as to introduce among its congregation, at the pulpit as well as in confessional booths, the notion that communism was harmful and evil. Being that Brazil was a predominantly Catholic country at the time, the Church was viewed as being an actively potent adversary to communism.

JC: Does the British government still maintain classified documents related to Brazil’s 1964 coup?

GC: It is possible that the UK’s National Archives still has documents about the 1964 coup that have not been released for public review. However, it is more likely that many of the reports that are already available remain with redacted passages, concealing names and other confidential information, as I observed during my research. After all, as I have mentioned, what was released to the public was not released in its entirety.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com