Preface

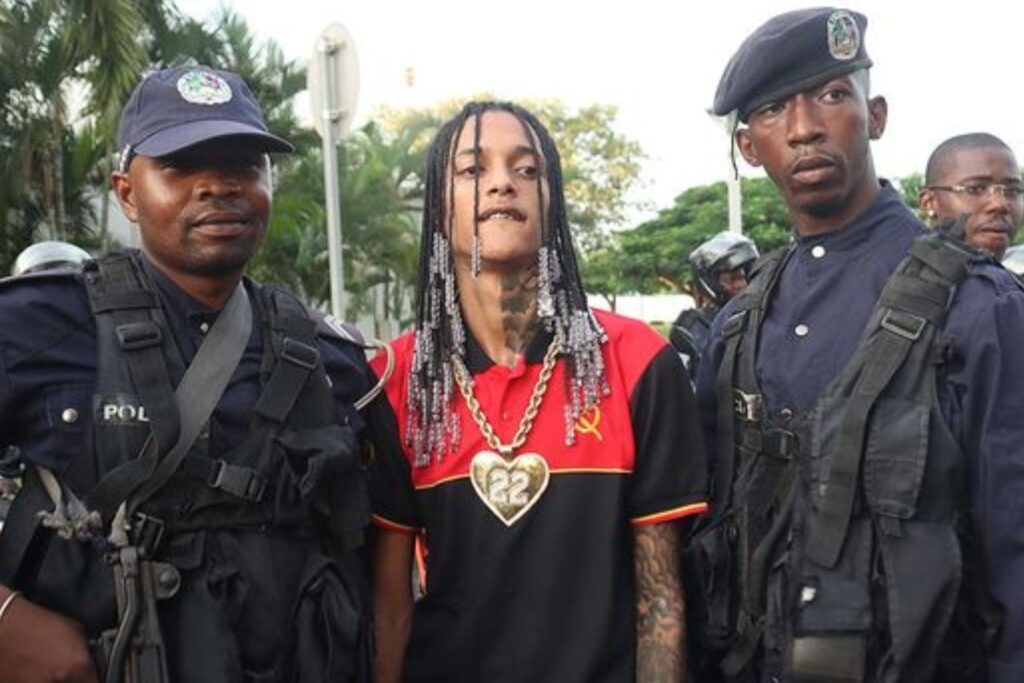

Evidence related to local Rio de Janeiro intelligence operations in these matters have not been ascertained. Incidents are fairly new and ongoing. Two separate arrests of the main subject of this investigative series occurred over a two-week period in February 2025: One was for reckless driving; the other involved an authorized police raid on a rented house. While searching the residence for a firearm discharged by the subject weeks earlier and posted on social media, officers detained Pará (Yuri Pereira Gonçalves). Accused by Rio de Janeiro’s public prosecutor of being a Comando Vermelho (Red Command or CV) gang member, he had been on the lam since 2020. Pará is also accused, along with 41 other alleged CV members, of a litany of crimes, including extortion and receipt of stolen goods. Police telephone wiretaps, allegedly, also connect him and other assailants to a cargo truck robbery.

“He came to play video games,” said our subject, claiming he had no knowledge of the arrest warrant issued for Pará and that his friend “is not a drug trafficker.”

Released on bail hours after his arrest in both cases, an avalanche of negative and defamatory media reports accompanied our subject every step of the way. Notwithstanding the press’s appetite to trivialize these events, politicians have also seized the opportunity to play moral judge, singing to the chorus of detractors by proposing legislation against him.

In light of mounting persecution, an explanation as to why this is happening, and which may involve coordinated intelligence operations, is herein presented. Because, if you have not heard, “The biggest war against organized crime starts now!”

Introduction

“I surrender to no one, that’s the state’s problem… a crook who’s a crook is always respected,” is a lyrical excerpt from the song 22 Meu Vulgo (My Alias, 22).

The number 22 refers to Article 22 (1940) of Brazil’s penal code which states that mentally ill patients, by law, cannot be held accountable for criminal acts. It is also slang to refer to somebody as “crazy.”

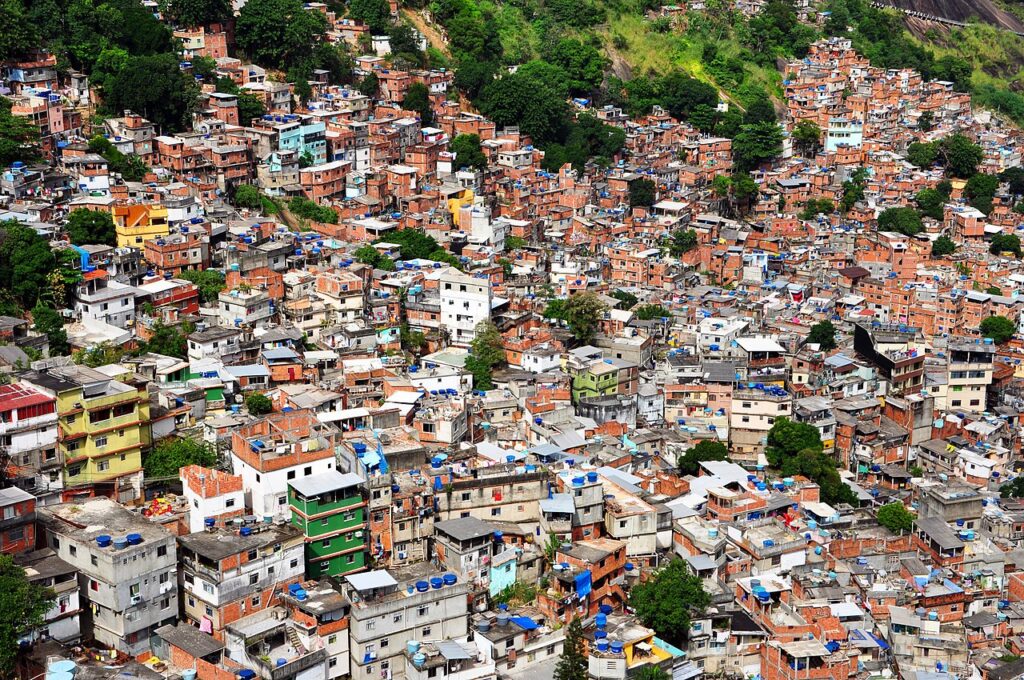

To casual ears, lyrics of this nature suggest an irrefutable admission of guilt. Toss whoever wrote them behind bars. To others, they translate quite differently. Synthesized from the impoverished, criminalized experience of favelados (favela community members) and other underserved territories, what they hear is the diametrical opposite. Born from hardships that are anything but happenstance, necessity compels them to ally with those who speak truth to power, those who resist the disorderly, systemic status quo.

Let’s commence deliberations from the perspective of haters.

Unequal to proven actions, guilt can be interpreted and established on words, even inferences. Based on the aforementioned lyrics, might any prosecutor present physical or documented evidence to support any claim of criminal behavior or incitement of such? If this question must be abided, the following, in no uncertain terms, is true. No judicial guardrails or litigative ethics hold Brazilian media outlets to such standards. When public opinion is up for grabs, the press and social media platforms, for those who own them, will crank out story after story aligned with their interests every step of the way.

This is the case of Oruam.

Oruam on Brazil’s Political Agenda

“I surrender to no one, that’s the state’s problem… a crook who’s a crook is always respected,” was written by 25-year-old Oruam (Mauro Davi dos Santos Nepomuceno), a funkeiro (funk music performer), rapper, trapper and the protagonist of this series, 22 Meu Vulgo has soared to 5.5 million YouTube views since it was posted in mid-2024. The artist has also amassed a Spotify fan base of more than 13 million monthly listeners. In short, Oruam’s lyrics are open to generous interpretation, blatant misinterpretation, or otherwise. Consequently, they have drawn the pulsating ire of Brazilian media, not to mention political heads.

Media Spin and Attacks on You Know Who

… We’re all fugitives from injustice but we’re going to be free / And your rules and regulations they don’t do the things we need…

— Lyrics from “What About Me” by Richie Havens

From the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Oruam’s popularity is not limited to Brazil. Audiences in Angola and Portugal have flocked to see him perform abroad. However, arrested in Rio de Janeiro twice in February and the proud son of Márcio dos Santos Nepomuceno (Marcinho VP), the alleged ex-leader of the CV street gang, Oruam has quickly become the poster-boy for everything that’s wrong, corrupt and criminal in Brazil—no small feat. His father, a political prisoner according to his legal defense team, has been imprisoned since 1996.

Since Oruam has been publicly advocating for his release, just flip on the Brazilian daily news or slew of cop programs and there they are, reporters and program hosts running a muck with the latest scoop on Oruam this, Oruam that, Oruam being detained and immediately released on bail, a barrage of negative publicity for general consumption. Nothing short of a traveling circus, popular television shows and networks like Balanço Geral, CNN Brasil, and SBT News, with over 19 million aggregated Youtube subscribers, have shadowed the rapper while ignoring more serious socio-economic crimes to which they, and Brazil’s employment sector as a whole, can hardly be disassociated.

The top two comments posted on one of the CNN Brasil reports read: (1) Beautiful attitude on the part of the police by promoting a reunion between father and son! (Oruam’s father has been imprisoned since 1996). Displaying an equal degree of disdain, the second combines an air of superiority with regret. (2) How sad it is to see our youth have someone like this as a role model. To exemplify the gulf between how one might interpret Oruam’s work, the top two comments posted on his 22 Meu Vulgo YouTube page are: (1) Absolute best; (2) Me.

Politicians Take Aim

Politicians, on the whole, either through commission or omission, have leaped onboard the defamation train. At the vanguard is São Paulo Councilwoman Amanda Vettorazzo tabling an Anti-Oruam Bill and creating a website with the same title. The legislative proposal seeks to prohibit the use of public funds earmarked for musicians and other artistic professionals who, allegedly, “incite organized crime or the use of drugs.”

Vettorazzo sums up Oruam as “one of the most famous rappers in the country who has gone viral making music and doing shows inciting organized crime, mainly the faction controlled by his father Marcinho VP.” Convicted and sentenced to 48 years in prison for allegedly ordering the killing of two rival gang members and other crimes, Marcinho VP was sent to prison in 1996. “I’m accused of being a drug-trafficking kingpin ever since I’ve been on the streets, since I was 17 years old… I’ve never been a drug-trafficker in my life,” he said, admitting bank and armored truck heists as his mode of operation. More on Marcinho VP later in the series.

Oruam, added the councilwoman, has, “opened doors for other rappers and funkeiros to start making music,” citing criminals and gang leaders “use of slang and other expressions to normalize the world of crime.” Vettorazzo’s crusade is condensed on her website’s homepage which is called Anti-Oruam Bill. “Councilmen and women across Brazil, the time to act is now! The biggest war against organized crime starts now!”

The proposed legislation has been scheduled for debate in parliament by Congressman Kim Kataguiri and is supported by São Paulo Mayor Ricardo Nunes.

“They [politicians] have always tried to criminalize funk, rap and trap [music],” Oruam posted on social media in response to the bill bearing his name. “Coincidentally, as the universe has made me, the son of a drug dealer, famous, they’ve found the perfect opportunity to do it. I’m on their political agenda. However, what you don’t understand is that the Anti-Oruam Bill not only attacks Oruam but all artists on the scene.”

Referring to Vettorazzo as an “idiot,” Oruam also noted, “We rap about what we see. When a playboy does it, inciting something he hasn’t experienced, nobody says anything.”

No Surrender

Delving deeper into the facts supporting Oruam’s artistic position offers greater insight and meaning into his lyrics, especially the one cited in the Introduction.

In terms of hard economics, last year (2024), Brazil’s per capita GDP grew by 3.4%, breaking its previous 2013 record. International tourism also soared to record heights, raking in more than $1 billion USD, as the currency exchange rate on the last day of 2024 calculates.

Despite new, chart-breaking economic feats, the Institute of Teaching and Research (INSPER) published a 2024 report titled Salary Loss From Racial Inequality. The findings show black workers, and apparently those unemployed, in Brazil “lose” over $19 billion (USD) each and every month due to “racial inequality.” As racism is, purportedly, outlawed in Brazil according to law no. 7.716 (1989) and 14.532 (2023), the study result will be restated for legal clarity. “Racial inequality,” or racism, in Brazil’s employment sector robs Black adults, young adults, mothers, fathers, their families and community in excess of $19 billion (USD) every single month of the year.

“Brazil is an invention of European capitalism,” sociologist Octavio Ianni puts it, one that prides itself on the creation myth of racial democracy. In this tropical paradise, poverty, favelas, “quebradas” (ghettoes), and underdevelopment need “taking care of [cuidar],”—in the best interpretation of that ambiguous expression, not the media’s biased approach to Oruam.

Having lived in Brazil for seven years, data outlined in “The Salary Cost of Racial Inequality” report is a bitter reminder of a recent, frank conversation I had with a close friend from the small coastal town of Prado in southern Bahia. Lifelong MST (Landless Workers’ Movement) militants, she, her sisters and other family members relocated to Portugal in the past years. “The left has some unique points of view,” she told me, “however, most politicians are the same. It is we base supporters who carry them on our backs. That’s all I can say. Understand?” Without going down the ideological rabbit hole on this one and long sensing she identifies with the Brazilian left, I told her I did. “As far as politicians are concerned,” she concluded, “we build steps so they can reach the top. To have a more dignified life, we ended up exerting plenty of effort to leave Brazil.”

Press coverage is mostly stonewalled about systemic, crippling economic effects upon Brazil’s largest demographic group, preferring, instead, to tighten their distractive lens on a music artist from Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, portraying him as public enemy number one. The guise is not only taken to take on the cultural front but, in some respect, on the international stage.

“Systemic racism appears to have endured since the formation of the Brazilian State,” wrote UN Special Rapporteur Ashwini K.P. in her report after visiting Brazil August 5-16, 2024. Racism persists “despite courageous and sustained advocacy amongst anti-racism human rights defenders, and people of African descent constituting the majority of the population…Endemic structural violence and exclusion, which dehumanizes those from marginalized racial and ethnic groups, causes often irreparable harm, and renders people invisible within society.”

Visibly Audible

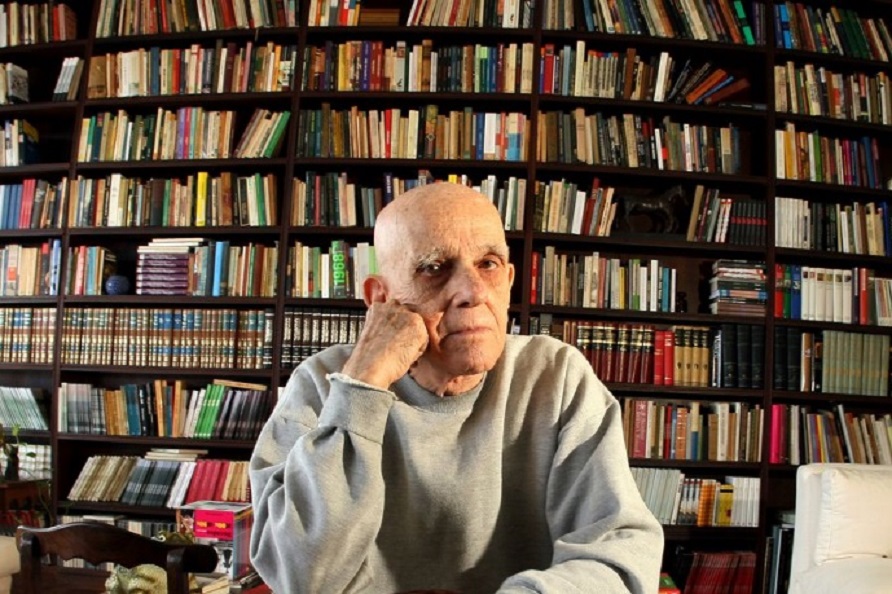

Fresh out of invisibility and going against the status quo, Oruam, in his own way, is giving Brazil a run for its loot. Despite adversities galore, he has achieved success through home-grown, community-based culture, unsponsored and uncontrolled by Brazilian media and elitist cultural and artistic hubs. Moreover, Oruam is instilling a sense of renewed pride, self-reliance and independent-thinking throughout the favelas, far beyond the clamoring chorus against racism as witnessed on the soccer field and apart from the mostly played out, binary and oversimplified left-wing vs. right-wing political establishment. When Brazilian media and society tells the favela no, Oruam tells them yes. Yes you can. Responding indignation, fueled by insatiable de jure racism and a painful sense of self-entitlement could not be more pronounced, as well as hypocritical. Take the late Brazilian author Rubem Fonseca, for example. No legislative proposal has been tabled to restrict access or ban any of his literary work. despite publishing stories that can be readily interpreted as criminal or inciting criminal behavior.

“I switched off the headlights and accelerated. Upon impact, I knew I had to drive completely atop her,” Fonseca wrote in the short fictional story “Nocturnal Rides” (Part 2), which, portrayed through the voice of a male protagonist, depicts in riveting detail luring a young female to a dark street in Rio de Janeiro and trampling her to death with one of his fancy automobiles. “No way could I run the risk of leaving her alive. She knew too much about me and, unlike the others, none of whom had escaped, Angela was the only one to have seen my face and my car.”

Fonseca was a 2003 recipient of the Camões Prize, the most prestigious literary honor awarded jointly by the Brazilian and Portuguese governments.

Whether or not the media targeting and political persecution of Oruam can be attributed to intelligence services will only be known with further investigation but considering, at face value, how fast he has been pounced on and, seemingly, in coordination, it is not beyond consideration. To date, the law can only attest to the fact that he earns an honest living from his music and, if you will, rising to the challenge of strict adversity.

“The most valued treasure anybody has in life is freedom, understood? Freedom is not bought. It’s earned,” Oruam explains. “This is what I speak about in my album, the freedom to come and go [as you please], to be you, to be proud of where you came from and what you’ve become, the freedom to love and much more. The launch of my album marks a new phase in my career, an Oruam different from what people know, understood? I put various ideas and feelings into the music I wrote. My family has always been my source of inspiration and they’re part of this album too.”

Stay tuned for Part 2 of “Republic of Oruam.”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com